As Neema Avashia tells it, "Put simply, my father needed a job."

The daughter of a doctor who immigrated from India in 1969, her parents first lived in Queens, New York, where her father did his residency, then they moved to West Virginia when her father was hired by the Union Carbide plant in the town of Institute. Avashia was born and raised in West Virginia.

Along with the promise of work, her parents, upon visiting Appalachia for the first time, "found the lush greenery and mountains of the Mountain State, so different from dry and dusty Gujarat, deeply alluring."

Avashia and her family lived on a street called Pamela Circle, in a predominantly white neighborhood where the streets were named after the developer's daughters. She celebrated festivals with other Indian families in basements, went over to a beloved neighbors' house for meals (mostly side dishes, as she and her family were vegetarians), played basketball and dreamed of being a writer.

As she says, "People have a lot to say about where I was from."

Related: Why is Joe Burrow so great? Because he's from Appalachia

It was the lead-up to the 2016 election that prompted Avashia, who teaches middle school, to write about her own experiences growing up in West Virginia. "The volume just went way up on the way people were talking about Appalachia, the narrative that existed around who Appalachians were, what they believed. And not seeing myself reflected in that narrative, thinking about my experiences growing up and how they didn't align, pushed me into a place where I was like, OK, I want to write about this and I'm ready."

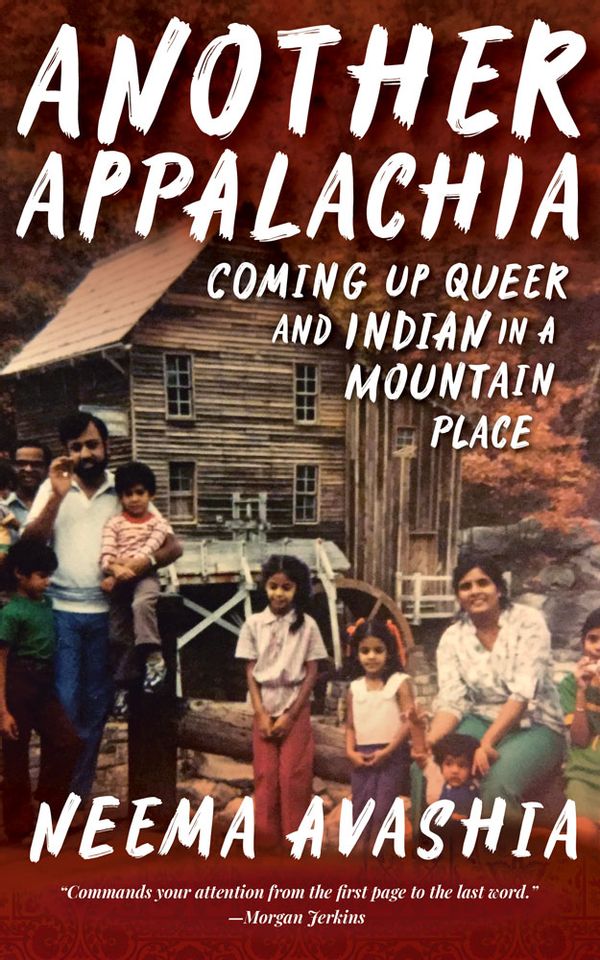

Her book "Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place" was published this month by West Virginia University Press. She spoke with Salon about the book, being a queer desi Appalachian woman in a complicated part of the country people think of as only white, found family and home.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

There are so many lines in this book that I underlined and so many quotes that I'm going to take away from it, but I think one of my favorites is the line: "Be family in the way that people need you to be." Could you talk about what found family means to you?

Found family is at the core of who I am. It's such an interesting thing because found family is something we associate so deeply with queerness in this country, but it also, for me, is so present as someone who grew up in Appalachia.

Because my biological family, by and large, was 8,000 miles away in India. We had a couple of family members who were scattered in other parts of the United States, but we didn't see them often . . . But I am so lucky to have grown up on this amazing street called Pamela Circle with these neighbors who, while on the surface, had absolutely nothing in common with our family, just completely opened their homes and their arms to us and were like, we got you. We're here.

"Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place" by Neema Avashia (Than Saffel / West Virginia University Press)That idea of showing up for people based on what they need, not based on what you think they need, but based on what they're telling you, is something I saw modeled from so early in my life. And it was mutual. It was my parents showing up for neighbors in the ways that they could and knew how to, whether it was their cooking or medical skills. One of my neighbors, he knew my dad loved figs — and figs were pretty much impossible to get in West Virginia in the '80s. They were this marker of my dad's Indian growing up that he couldn't get anymore. My neighbor planted a fig tree for him.

"Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place" by Neema Avashia (Than Saffel / West Virginia University Press)That idea of showing up for people based on what they need, not based on what you think they need, but based on what they're telling you, is something I saw modeled from so early in my life. And it was mutual. It was my parents showing up for neighbors in the ways that they could and knew how to, whether it was their cooking or medical skills. One of my neighbors, he knew my dad loved figs — and figs were pretty much impossible to get in West Virginia in the '80s. They were this marker of my dad's Indian growing up that he couldn't get anymore. My neighbor planted a fig tree for him.

He knew my dad was missing figs from home. And so, he planted that tree . . . My dad tried to teach me how to drive. That same neighbor was like, I'll do it. He would pick me up and he would take me on driving lessons every week . . . It was: I see a gap, I'm going to fill it. You have a need, I'm going to meet it. That just is so core to how I was brought up, and I think it's become an integral part of who I am and how I think about how we're supposed to be in relationship with each other or what it means to be in community.

That is something that struck me as well, because it's been a big part of my life living in Appalachia and raising my son there. It's something that I feel people don't always understand about the region: that the community helps people, helps strangers. There is mutual aid going on that's been going on for generations, that people may not know about.

I just saw it all the time: people giving so freely even when they might not have had that much themselves. It wasn't transactional. It was: There's a gap, we've got to fill it. That's how you take care of people. You fill the gaps. I think there's something about rurality and isolation that also supports that because you're not going to get it from somewhere else. There's not anyone else to give it to you, so if you don't rely on each other, it's just not going to happen.

That is so different from my life now living in a city, where everything is theoretically at your fingertips. I think it makes people a lot less able to ask for help because it's so available. You can get it. And so, you feel like, I shouldn't ask for it. I shouldn't have to ask anybody to cook for me when I'm having a hard time or a health issue because I can just order something really quickly. It's just different. There's a difference in the decision making. There's a difference in that whole experience than when your neighbor knows that you're not feeling well and they just bring food over to you because they know what's going on.

I wonder, living in a city myself now too, which has been a shock for me, I wonder if people are less likely to help here because there are so many people there's just the assumption that somebody else will help? Somebody else will step in. Versus like you said, in a more rural place, you may be the person who has to step in. There's nobody else.

Responsibility doesn't get diffused in the same way. Living in a city during a pandemic, it's been revealing to see the ways in which people struggle here with how their life has changed. In some ways, I think rural people and people in Appalachia were just more prepared for this. When you're not seeking external stimulation in the form of going out all the time as the way that you entertain yourself, and when you have to slow down your pace — I think a lot of people in the city didn't know how to do that.

We're just going to stay home? I don't know how to do that. Meanwhile, growing up, all we did was stay home or go to someone else's house. That's what there was to do. It just made me think a lot about how much there is for the rest of the country to learn from Appalachia about ways of being in community with each other and just ways of being — yet, that's not the paradigm ever. I don't think New England thinks it has anything to learn from Appalachia. And yet, I think New England has so much to learn from Appalachia.

When you were growing up, how you did stay connected to your identity as a person of color, your history and your traditions, while you were living in a place where, as you write, the total non-white population has never exceeded 5%? How do you hang on to who you are?

It wasn't easy. I write a lot in the book about the messages, the kind of critique that was present all the time: the critique of difference. But I was super lucky to have a small Indian community to fall back on. And that's not a thing that everybody has. I think there are a lot of folks of color living in rural areas who don't have that group.

In school, I was often the only person of color in my classes. On the weekends, I would get to go to spend time at the houses of my aunties and uncles, and I'd be with their kids, and I would be in spaces where everyone did look like me and did speak the language that I spoke and did practice the faith that I practiced.

Having that space, I think, did allow me to feel like: Okay, this is a part of myself that I don't know how to bring into school or that I don't feel like is welcome in school, but I also feel like this part of myself is affirmed in these other spaces. It does get affirmed on the weekend. It does get affirmed when we get together and have these rituals and celebrate together. And so, I think those messages of affirmation — I don't know that they were always enough. I'm not going to make it seem like it was easy or seamless, but I think in the long run, there was enough of that happening that it did mitigate a lot of the harm that was happening in spaces where my identity wasn't reflected.

One part of the book that I really enjoyed is the chapter about Mr. and Mrs. B and how they first connected with your family because they invited you over for food. That hadn't really happened before because people in your West Virginia community didn't know how to cook for vegetarians at that time. I wonder if you could talk a bit about food and how it has a role in your life as someone who's Indian and Appalachian?

Food is one of those places where there's such overlap. It's 100% at the core of Indian culture and it's 100% of the core of Appalachian culture. It was a way that my family was able to build relationships across lines. My parents had lots of friends who were white West Virginians, and what we did is we shared meals. They weren't just inviting Indian people to our house; they were inviting white people to our house, and we were going to white people's houses and we were cooking and sharing together.

This was the '80s. There wasn't the internet. There weren't tons of recipe books about vegetarian cooking. People were having to stretch or to think in different ways. But I do think some of those early relationships ended up being with people who just loved cooking and loved sharing meals and wanted to be in that conversation . . . My mom would make Indian food for a lot of my friends growing up. Their first introduction to Indian food was in my mom's kitchen. There wasn't an Indian restaurant in Charleston until the mid-'90s, but a lot of people had Indian food before then because they were eating it at our house.

It was this interesting back and forth where I ended up becoming a connoisseur of both kinds of food. What vegetarian foods can I find in Appalachia that I really love and I'm excited about? And then also, what are the ways in which I'm bringing people into my house to explore this other cuisine?

Aa an adult, it means that when I cook I'm always pulling from both of those places. Both of those traditions have formed me. I will just as quickly make biscuits as I will make khichdi, which is a lentil and rice dish that my mom loves to make. Those things just happen at the same time for me. They're both part of my way of thinking about what I do in the kitchen.

Do you still think of West Virginia as home?

I do. I've lived in Boston for almost 20 years and I can't get myself to call it home. I feel like it's a failing. I should be able to say this. I've lived here for a really long time, but I can't do it. It doesn't feel like that. A lot of people who are expats from Appalachia, the thing that's interesting is we all know that feeling of home that we had — but that doesn't mean it exists anymore, either. It is a very weird thing to feel like you're looking for a sensation that you're not sure actually exists anywhere anymore.

Because you can't go home again. Even though I know you wrote in the book about how you visit West Virginia a lot, it's still not the same.

It's not the same and it can't ever be the same. The people aren't the same. The whole context has changed. The community where I grew up, the brain drain that's happened, the loss of jobs — it is not the same place. In a lot of ways, it's hard to recognize. It gets harder to recognize every time I go home. And so, West Virginia is home, but I think it's a West Virginia that is a construct in my head, and not necessarily the reality, if that makes sense.

It's the past. The memory is home.

Yeah. That's right. The memory is the closest to home I ever feel.

What has the reaction to your book been? Have you talked to people from home about it?

Some of the best reactions have been from my peers who I grew up with in West Virginia who were also Indian. One of them emailed me a couple weeks ago and he was just like, I thought we had this strange niche experience of growing up in West Virginia that no one would ever understand or believe; I just can't get my head around the fact that not only are people going to believe it now, they're going to read a whole book about it.

There's an affirmation of that experience that I think is powerful for other folks who had that experience growing up. And so, that's been really lovely. But also, my book debut was a couple of nights ago and there was a young woman from West Virginia in the crowd. There was this moment where she was just surfacing tension she feels within herself about whether to stay here or go home. Then, I have a colleague who's from Puerto Rico, who after the reading was like: I never would've thought I would have something in common with someone from West Virginia.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

What I'm starting to hear from people is: I'm not Indian or queer, or maybe even West Virginian, but there's something that I'm seeing in this book that resonates for me. I keep finding myself here when I didn't expect to.

That reaction feels really, really lovely because that was the goal. It wasn't just trying to write a book that was: Here's this thing. I grew up Indian in West Virginia and you should just be shocked by that fact. I wrote a book because that experience of being queer and being Indian in West Virginia made me have a lot of questions that I think are questions that so many of us are grappling with all the time. Questions about identity, questions about community, questions about what it means to love places that are enacting policies that want to erase us.

There are about 30 states in the United States where that question is coming up for people right now. These aren't just personal questions. I think they're pretty universal. I think this is a good book for people to be reading in this moment. It felt good to see people recognizing those questions as ones they also have.

I do feel like that we are moved the most and we learn the most from specific stories, and that we can take those universal questions and longing and truths from the very specific lens that you've placed on your life.

People might think I'm cheesy, but I actually think it's the only way forward. We are in such a polarized moment. I don't know what else we have besides stories right now. People are so unable to see each other face to face, or see each other on social media, or see each other in these contexts, so it's like, can you see someone if you just will read a book? Can you see outside of yourself and see this other person and find empathy for them?

Is story the only way that we're going to surface that empathy in people and find a way that is not this intensely polarized space? I could be totally wrong, but it's the only thing I feel like I'm hanging onto right now: that maybe narrative is our way through.

More stories like this

Shares