It seems as though "magic" mushrooms containing the psychedelic drug psilocybin are suddenly in vogue, judging by the sudden pop up of shroom dispensaries across North America and the fact that Colorado recently joined Oregon, Connecticut and Maryland in legalizing psychedelic therapy (though no clinics have opened yet) — plus the upward trend in "microdosing" hallucinogens, a new Netflix series, and on and on.

But humans have been consuming these fungi for thousands of years, and some theories suggesting our ancestors even ate them millions of years ago. Ancient humans probably consumed these psychoactive mushrooms for good reason: in some people, psilocybin seems to stir creativity, spiritual connectedness and alleviate mental health pitfalls like depression and anxiety.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration clearly sees potential in psilocybin. They've awarded the drug "Breakthrough Therapy" status for depressive disorders not once, but twice — first for Compass Pathways in 2018 and a second time with Usona Institute in 2019. This label helps the drugs move more quickly through the pharmaceutical approval process, though it doesn't always equal success. The latest estimate is that psilocybin will become an FDA-approved drug before 2026, but there's no guarantee this will happen. In the meantime, psilocybin remains highly illegal at the federal level.

But while psilocybin could someday be coming to a Walgreens near you, it may not involve mushrooms in a pill bottle. Instead, it may likely be a synthetic version of psilocybin, perhaps even brewed from a vat of bacteria, no fungus required. In that sense it is akin to a nicotine patch compared to a cigarette: one is a single drug distilled, the other is the original substance from which it grew. This extraction process begs the question: Is anything lost by moving from a naturally-derived drug to a human-made version?

Some experts argue that yes, there is a difference between synthetic psilocybin and mushrooms. In fact, multiple startup companies are betting this is the case, dumping millions into researching the question. But critics say there isn't enough evidence for one over the other yet, and that this pursuit could be more about securing patent rights to unique drug formulations.

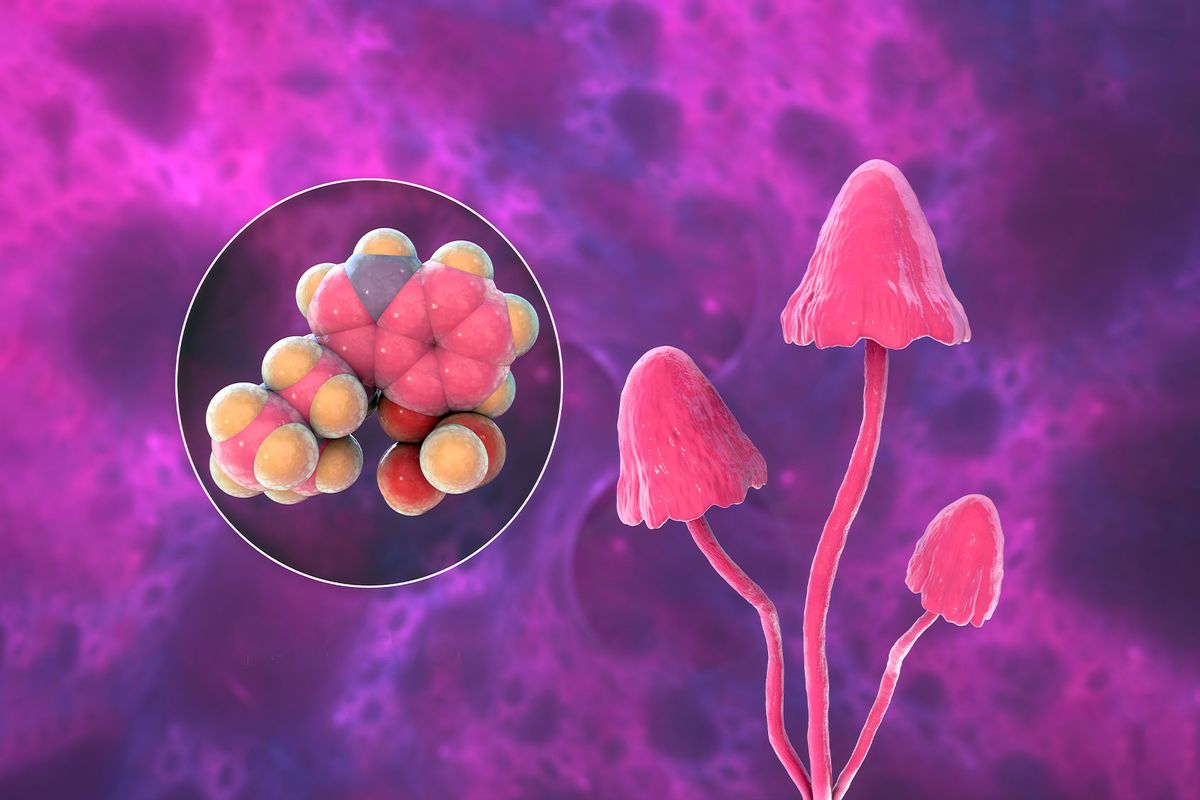

There are over 180 species of psilocybin-producing mushrooms, scattered across the globe, none of which evolved this drug to benefit humans. Instead, scientists believe that these fungi developed these compounds to either attract or repel pests, possibly both. Regardless, psilocybin works in our brains because it closely resembles the neurotransmitter serotonin, which helps all kinds of processes related to mood and perception.

"The entourage effect is kind of the idea that the sum of all of these individual compounds, this cocktail in the magic mushrooms, is the effect of that could be greater than the individual parts."

But psilocybin isn't the only interesting molecule that these mushrooms produce. There are a bunch of other compounds that are similar in chemical structure. The four main ones that scientists are curious about are norbaeocystin, baeocystin, norpsilocin, and aeruginascin. Other molecules present in the mushrooms, such as amino acids, enzymes, and other chemical compounds may also play a supporting role. This would constitute a sort of "entourage effect," a bunch of drugs in a botanical or fungal mix that work together to create a more robust experience.

While psilocybin gets all the credit, other compounds in mushrooms could be modulating psychedelic experiences. Stripping them away could mean that whatever product Compass or another company brings to market could be less effective than what simply grows in cow dung (one of a psilocybin mushroom's favorite places to live.)

"The entourage effect is kind of the idea that the sum of all of these individual compounds, this cocktail in the magic mushrooms, is the effect of that could be greater than the individual parts," Ryan Moss, the chief science officer at Filament Health, a psychedelic startup based in Vancouver, B.C., told Salon. The company's primary aim is to "extract and standardize stable doses of natural compounds from magic mushrooms," as explained in a press release celebrating patents Filament was issued related to this process.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Earlier this year, Filament partnered with the University of California, San Francisco to conduct the first FDA-approved clinical trial administering 20 patients with psilocybin derived from mushrooms, as opposed to synthetic versions. The goal is to determine if patients notice any difference, including more consistent trippy experiences, faster onset (no more waiting an hour or more for them to kick in) and reduced side effects. But results probably won't be available until late 2023, Moss said.

So far, "There's not a lot of evidence other than anecdotal evidence," Moss said of the entourage effect in mushrooms. "But there's no question that magic mushrooms have a lot of different metabolites in them. And to say that's exactly the same thing as synthetic psilocybin, I think is just as silly as saying that the entourage definitely exists."

The phrase entourage effect was first applied in 1998 as a way to explain a unique component of endocannabinoids, a type of chemical the body naturally makes that are like THC and CBD, the active ingredients in marijuana. It's since been co-opted as a marketing term for the emerging cannabis industry as a way to sell different varieties of marijuana based on potency and effects. The evidence for an entourage effect is still being determined and more research is needed. Part of the reason is because it's not an easy question to study in clinical trials and the legal status of these drugs makes research expensive and marred by red tape.

"Doing drug trials on natural products is very, very difficult because in order to get an approved to do a study, you first have to establish that you can produce a consistent dose and purity of the drug product," Dr. Alan Davis, a clinical psychologist and the director of the Center for Psychedelic Drug Research and Education in the College of Social Work at Ohio State University, told Salon. "The FDA requires that kind of data in order to let you test it in humans. That's one of the things why all the psilocybin trials have been done with synthetic psilocybin and not natural mushrooms."

Recently, Filament announced development of medical grade ayahuasca. Ayahuasca is yet another example of an entourage effect in psychedelics, but this one actually has some evidence behind it. The hallucinogenic brew is actually a mixture of multiple plants, with recipes varying from region to region, but usually contain a plant with the psychedelic DMT and a vine with a drug called an MAOI.

DMT isn't active orally unless taken with an MAOI. So in order for ayahuasca to be trippy, consumers need both plants. But for now, the evidence that such a phenomenon exists in cannabis or mushrooms is pretty thin.

"My bias, which I'll state very clearly, is that I think that the for-profit enterprise in psychedelics right now is, in general, a system where people are positioning themselves to make as much money as possible," Davis said.

Still, some companies are trying to find evidence for this. CaaMTech, a biotech startup that has been exploring the entourage effect in mushrooms for several years, recently published the results of a study exploring how for psilocybin, baeocystin, aeruginascin and related drugs bind to receptors in the brain. The research, published last month in the American Chemical Society's journal Pharmacology & Translational Science, adds to the evidence that baeocystin and aeruginascin are not psychedelic. They still seem to bind to serotonin receptors in the brain, however, meaning they may still produce some therapeutic effect. But it's still not clear if these molecules are working together, let alone how.

Whether these companies land on a more effective psychedelic formulation than synthetic psilocybin is yet to be seen, but there could be other motivations for these alternatives: profit. Generally, it's not possible to patent molecules like psilocybin that occur naturally — but it is possible to patent formulations, such as the proprietary blends that CaaMTech and Filament are developing.

"My bias, which I'll state very clearly, is that I think that the for-profit enterprise in psychedelics right now is, in general, a system where people are positioning themselves to make as much money as possible," Davis said. "So when I hear of a for-profit company examining the entourage effect of psilocybin mushrooms, what I hear in that is, 'We're looking to see whether we can isolate a combination of substances that we can market as our own drug that then we can make money off of it as a proprietary substance.'"

"Whether or not that's actually what they're doing, I don't know," Davis went on, but he noted that the amount of money being invested in this research suggests someone is expecting a return on investment. "If they can market and trademark let's say, a combination of psilocybin and three other alkaloids in the mushroom, well, all of a sudden, now they have a product that's theirs that they can charge as much as they want for."

Humans have likely been eating magic mushrooms since before recorded history. It's not clear if we'll be taking synthetic psilocybin or mushroom-derived blends in the future — maybe a little of both. But an alleged entourage effect in mushrooms tells us there's still a lot to learn about the benefits of these fungi and more research into this potential phenomenon could yield even more effective psychedelic drugs.

Read more

about psychedelics

Shares