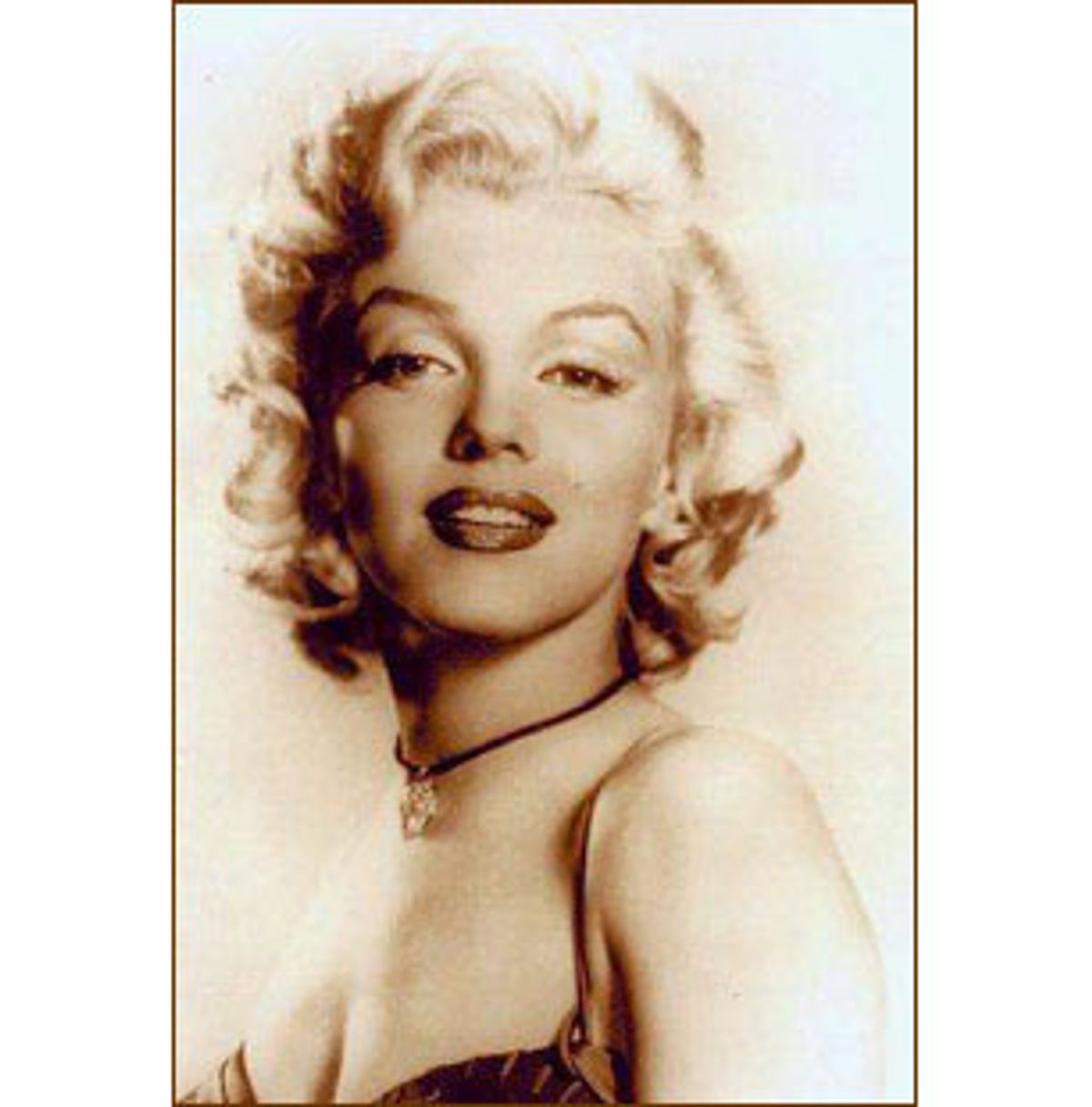

"What she has," said one of Marilyn Monroe's acting teachers, "this presence, this luminosity, this flickering intelligence ... [is] so fragile and subtle, it can only be caught by the camera. It's like a hummingbird in flight -- only the camera can freeze the poetry of it."

And indeed, hummingbirds dart through the pages of "Blonde" like tiny emblems of the imperceptible. Joyce Carol Oates' scary and rhapsodic novel about the life of Marilyn Monroe is saturated with the mysteries of eye and camera -- time, motion and stasis, light and dark -- as well as the mystery of Monroe's presence on-screen.

The still camera was always Monroe's friend. But perhaps because she understood it so well, the motion picture camera terrified her. Moviemaking was an agony for her and became so for everybody she worked with. She'd hide in her dressing room for hours: The love scene in "Some Like It Hot" required 51 takes; one conversation in "Bus Stop" took six days to film. And yet the directness and naturalness she achieved during these harrowing sessions consistently astonished everyone who'd been on the set.

On-screen she looks startled, as though she's so entirely present in the moment and in her glowing skin that she has lost track of the plot. Director Billy Wilder said she had "flesh impact," her flesh "warm and alive even in black and white." She hugs herself, wiggles her shoulders with the pleasure of inhabiting her body. The physical world is friendly, hospitable; even the air -- from the subway grating, the air conditioner -- makes love to her.

How did a perpetually frightened and insecure young woman summon up such powers of illusion? Out of what fathomless need did an illegitimate child who spent years in foster homes command so much attention and so much love, even 40 years after her death? How, out of a series of doomed affairs and marriages and some not-very-good scripts, did she manage to tell us so much about sex? And what kept her from ever satisfying her own needs for love and respect?

Oates presents her story as a tale of the grotesque, a horror story akin to Stephen King's "Carrie," another book about an unhappy child with a mad mother. Like most horror stories, "Blonde" is a tale of freakish overcompensation, impossible wishes granted, awesome power ill-used, demons finally undefeated -- the story of an injured child who can't be healed, even by the love of the millions. There's nothing supernatural in it, of course, unless you consider the immense sway that movie images and technology hold over all our imaginations.

Unlike genre horror fiction, though, "Blonde" is a huge, incantatory, expressionistic work that doubles back on itself to retell stories again and again, building its themes and variations through a seeming infinity of retakes. Description approaches hallucination. The action is told by numerous voices, some singular and famous, some anonymous and plural. Sometimes the narrative voice is breathless, almost gasping -- the ghostly Marilyn Monroe voice, oddly formal and well mannered, too high and thin for the body that produced it.

The childhood scenes in "Blonde" are pure irresistible Grand Guignol. In Oates' telling, Monroe's mother, Gladys Mortensen (also spelled Mortenson), is a frenzied, furious, star-stuck studio employee, fuming and quivering on the verge of psychic meltdown. Volatile, delusional, chain-smoking and sometimes setting the sheets on fire, she delivers endless apocalyptic rants based on serendipitous reading and a thousand movies. The reader (and little Norma Jeane, aka Norma Jean, as well) become transfixed, especially as Mortensen tells the terrified and adoring child on her sixth birthday that her father has promised to return and "claim" her.

He never does, of course, though Monroe waits all her life and calls all her husbands "Daddy." Or, more ominously, he's there all the time, in the movie reality at the back of her mind that always threatens to overwhelm her grip on everyday events.

Hyperreal and overwrought, the book stuns by its relentless energy. The most effective scenes (besides the opening ones of Mortensen) are the most brutally expressionist: the shooting of the famous nude calendar, the casual sadism of the studio heads, the icy cruelty of Kennedy and company. Less successful, I think, is a hokey, probably manufactured central episode having to do with Monroe's obscure affair with a sad, sexy, druggy Charles Chaplin Jr.

At least according to one biography, this affair between the fatherless starlet and the rejected son of a famous father really did occur, but the melodramatic fallout from the episode seems contrived to give the voluminous story some centrifugal energy. Perhaps it's necessary, as "Rosebud" was necessary to "Citizen Kane," but it reveals about as much about Monroe as Rosebud did about William Randolph Hearst.

Still, like "Citizen Kane," "Blonde" is a staggeringly effective piece of craftsmanship. The biographical aspect is fascinating and inescapable, but, as Oates warns us in an introductory note, "biographical facts regarding Marilyn Monroe are not to be sought in 'Blonde.'" People and events are manipulated, elided, exaggerated or radically foreshortened until they become the big screen images we vaguely remember from film clips or newspaper stories about Monroe's life. It's as though we're watching a series of movies, all with the same female lead: the Blond Actress and the Ex-Athlete; the Blond Actress and the Playwright. As Monroe painfully learned, once the studio had a winning formula, it wouldn't let it go; in "Blonde," Oates plays the studio's game to chilling, claustrophobic effect.

For example, she makes the Playwright -- the Arthur Miller character -- 48 years old when he begins his relationship with Monroe, instead of 38 or 39, as Miller really was (he was only nine years older than Monroe, and younger than Joe DiMaggio). I think she does so because the story plays more "Hollywood" that way: Contemporary magazine shots of Monroe gripping the arm of a New York intellectual with a receding hairline seem to tell the story of a young wife and a much older husband, so that's the story we get. The story the camera tells is always the primary story. "Blonde" shoots first and asks questions later, working from the outside in, faithful to the truth of appearances, both from Monroe's life and especially from her last movies.

She did become a better and truer actress during the last years of her life. When asked what character she played in the wretched "Prince and the Showgirl," she answered, "A person." And it's true. Silly and simple as Elsie the Showgirl is, she's a mensch -- the only one of Monroe's characters whom I can imagine walking off the screen into real life, taking her rueful, down-to-earth, grown-up sexuality with her.

I'm being sentimental here, dreaming in the way that the movie image charms us into dreaming, imagining her walking into the shadows like Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard at the end of "Modern Times." But Oates has built "Blonde" of tougher stuff, a substratum of imagery culled from the technology of the movies, the paradoxes of acting and the uniqueness of Monroe's screen image.

Laced with poetry about light and vision, "Blonde" doesn't end with a soft, comforting fade to black, but in the brilliant, disquieting light that comes up when a movie ends. Oddly assorted snippets of poetry and philosophy expand upon fear, visibility, loneliness. Taken from Stanislavsky, Emily Dickinson and Pascal, among others, perhaps the citations are nods to Monroe's constant, passionate, haphazard reading. In any case, I found them strange and beautiful, merging pop and poetics, metaphysics and melodrama, in an attempt to account for her personality's absences, her image's uncanny presence.

Was the power of her screen presence due to her audience's unconscious apprehension of her fear and loneliness? Maybe so; it is certainly so in "Blonde." But was her funny, intelligent and generous on-screen sexiness also the product of her personality's dissolution? Stupid as her lines were, her persona was smart enough to know her flesh's frailty, and self-conscious enough to find it amusing.

Monroe may have been cast as selfish, thoughtless, a gold digger, but her audience felt her eagerness to share the physical pleasure she seemed to take in being herself. In his book "Marilyn," Norman Mailer muses that while sex might be dangerous with some people, with her one feels it will be "ice cream." One of my girlfriends' mothers, approaching 70, confides that she's still sexually active -- "and it makes me feel like Marilyn Monroe." My husband and I rented half a dozen videos of Monroe's films the week before I wrote this review -- and felt pretty good ourselves.

"Blonde," of course, is anything but a feel-good book. It's eccentric, exhausting -- and remarkable. Part horror, part melodrama, part wildly adventurous meditation, it sees in the dark -- the way we all do at the movies -- holding the remembered and cherished image in our eyes while we wait for the shutter to open and the frame to advance.

Shares