Two weeks ago, a shocking video from an ill-fated cruise popped up on blogs and news sites. The clip, allegedly taken on a Pacific Sun cruise ship during heavy seas off the coast of New Zealand, shows the interior of the ship being rocked by a series of large waves. Crew members grasp onto walls for dear life. Furniture flies from one side of the ship to another, sending passengers tumbling through the air. Below deck, a full-size forklift is tossed around like a child's toy. At a time of super-sized and seemingly unsinkable cruise ships, the video is a terrifying reminder of the power of the open sea.

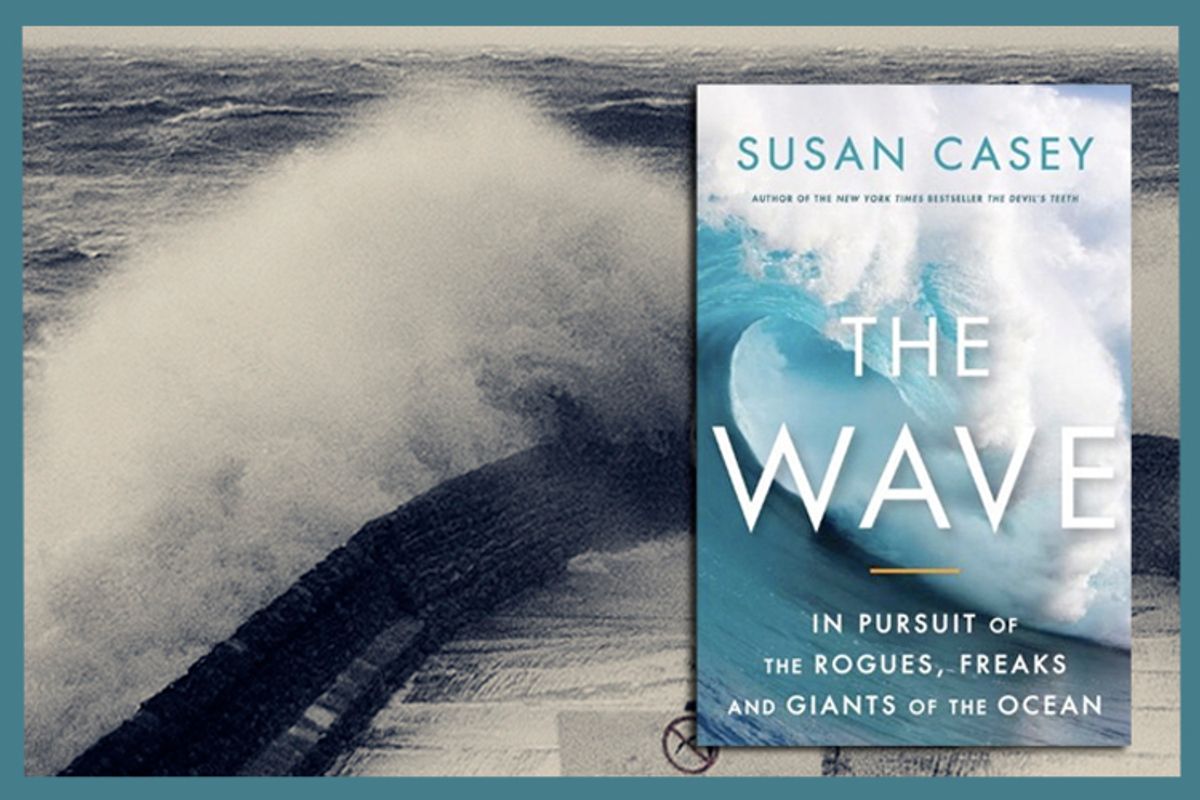

In her utterly engrossing new book, "The Wave," Susan Casey looks at the tremendous and still-mysterious power of large waves, like those that battered the Pacific Sun. Casey -- a longtime science and sportswriter, and the current editor in chief of O, The Oprah Magazine -- is most fascinated by the recently discovered phenomenon of rogue waves: singular waves that can be two or more times as large as the surrounding seas, and easily sink large ships, batter cruise liners, or inflict serious damage on 100-foot oil rigs. Two large ships sink every week, on average, across the world. Many can likely be attributed to these rogues, some of which measure over 120 feet in height.

As part of her research, Casey also visited a bay in Alaska known for creating the biggest waves known to man (including, in one case, a 1,740-foot super-giant), spoke to ocean experts about the dire effects of global warming on waves, and traveled with a group of surfers, including "tow surfing" legend Laird Hamilton, who specialize in tackling monstrous 100-footers. The book is a meticulously reported, relentlessly enjoyable and, at times, highly suspenseful read -- even for those of us who rarely venture into the water.

Salon spoke to Casey over the phone about mega-tsunamis, the world's increasing "steep wave" problem, and what, exactly, can create a 1,740-foot wall of water.

It seems like in the last few years, especially in the wake of the South Asian tsunami, there's been a lot more talk about the dangers of giant waves. YouTube is filled with videos of cruise ships being battered by rogue or giant waves.

Lloyd's of London is actually quite concerned about cruise ships. One of the guys said to me: "This is a high concentration of risk. You've got 5,000 people on boats that are getting bigger and bigger and they're going into gnarlier and gnarlier places." They're all over Antarctica now, for example. Recently, one of the hardier cruise ships got hit by a 100-foot rogue wave and all of its navigation equipment got knocked out and windows got broken. During another recent cruise in Antarctica, all the people ended up in the water, which isn't a good situation. By the grace of God, there was another boat nearby.

We've only very recently been able to prove that giant rogue waves even exist. Why did it take so long?

People who encountered 100-foot rogue waves generally weren't coming back to tell people about it. And the people who did were thought to be exaggerating. When satellites came along around the early '80s, along with better weather radar, and laser measuring devices, that helped people understand them a bit better. They could affix them to boats or ocean buoys and the readings were more accurate.

In 1995, there was a well-recorded incident on this oil platform in the North Sea. On a day when there were 38-foot seas, an 85-foot wave popped up and battered the platform. It was measured by laser. That's when the scientists really turned to one another and said: "What's going on out here? By the laws of basic ocean physics and oceanography that shouldn't happen." It took chaos theory, quantum physics and physics theories from light to understand why one wave can suddenly pirate the energy from four other waves around it and it becomes this unstable, teetering monster.

Why aren't people paying more attention to disappearing ships? If flights were disappearing over the ocean, everybody would be outraged and terrified.

When something happens to a ship in the Andaman Sea, and it's got a Laotian crew and it's a rust bucket to begin with, it's not going to make the front page of the New York Times. A lot of the things in the ocean are out of sight, out of mind. People think of it as a scary, dark, mysterious place, and to some extent it is.

But then you get a situation like the Derbyshire, which was the largest ship ever lost at sea. It went down with all hands in 1985, without any time to send a mayday signal. Because it was a British crew, all of the families of the lost seamen lobbied -- and got -- the British government to do three inquiries into the ship's disappearance. They probably encountered a wave that was 120 to 130 feet tall and it snapped the boat in half like a pencil. They found the stern about 10 miles away from the bow.

Why should people care that these giant rogue waves exist?

It's more than just shipping -- we're all affected because we live on a planet that's mostly made of salt water and the oceans control the climate. It's one of our most powerful forces of nature and it's basically unknown to us. That's a pretty precarious situation, especially if you consider that 60 percent of the global population lives within 30 miles of the coastline. When the tsunami hit in 2004, people were asking, "What's a tsunami? What do you mean a wave came ashore?" People acted like it had never happened before, but they actually happen pretty regularly.

Some people in the book claim that waves are getting bigger because of global warming. How sure are we that that's the case?

The extremes are getting more extreme. If there's a Category 5 hurricane, for example, it has the potential to be a stronger Category 5 hurricane. They haven't proved that the frequency is changing, but certainly the winds are higher. And there's really no denying a couple of things: The sea level is rising and the temperatures are rising, so there's more heat and energy in these systems. It's not rocket science.

There are also ominous implications for people who live at sea level in terms of potential storm surges.

Katrina was another big eye-opener. We're not going to be able to muscle around a 30-foot wave that's coming ashore. There are a lot of coastal erosion issues up north. The ice is melting, so waves that used to break on ice floes are now breaking right on land, which is eroding and the waves are coming in closer and closer. In Hawaii there is a huge issue with beachfront erosion; the waves are getting stronger eating away at the beach.

The most shocking factoid in the book is that, in 1958, a bay in Alaska was hit by a 1,740-foot wave, which is the size of the World Trade Center. How is that even possible?

That was the largest wave ever recorded. It took place in Lituya Bay, a finger bay in Alaska about halfway up through Glacier Bay National Park. It's an incredibly spooky place. It turns out it's basically designed by nature to create the biggest waves on earth.

In this case, there was a big eruption on the nearby Fairweather Fault, which thrust parts of Alaska 47 feet in the air. Tons and tons of rock and ice went plunging down steep hillsides into this bay -- it was like dropping a paving stone from a ladder in a bathtub.

So here comes this 1,740-foot splash wave. Scientists were able to determine exactly how big the wave was, because the forest and mountainsides were absolutely shaved. This has been happening over and over again in this bay and hundreds of people have died there -- native people, Russian seal hunters. The ripples that came out of it were 200 and 300 feet tall. Three boats were anchored there at the time. Two of the boats had the presence of mind to go straight at it, which is really counterintuitive but is the only way you survive. You have to get over the back of the wave before it crests. If you get caught in the lip, you're just going to be dead. That's what happened to the third boat.

How concerned should people be about an enormous wave like this hitting a more populated area?

Those things do happen. About 8,000 years ago a giant underwater landslide off the coast of Norway caused a wave that drowned parts of Britain. There are a lot of mountains and volcanoes under the ocean and when they start moving around in dramatic ways it can create giant tsunamis. But I don't think it's worth actively worrying about.

You spend much of the book following around a group of tow surfers, who ride enormous 60- to 100-foot waves. What is tow surfing, and how did it go from being this fringe sport to a miniature industry?

These are the extremes of the extremes. These guys are to surfing what astronauts are to pilots -- they're not really surfers. It's still a fringe extreme thing, even as a miniature industry. Forty feet or a little higher was the maximum wave size that people can actually paddle into because these waves are just moving too fast. It's like trying to catch the subway by crawling through the station.

[Tow surfing pioneer] Laird Hamilton's basic notion was that the coolest waves on earth were going unridden by anybody, so, along with other guys in Maui, he created a new sport. They took jet skis and tow ropes and reconfigured their boards so they were sleeker and heavier, but smaller, with foot straps so they could handle the pressure of the bottom turn. The early lessons of tow surfing were hard ones, but over the years it evolved to the point where they had really effective safety protocols. There were horrific injuries, and horrific fatalities, but when you consider what they're doing, it seems to be working pretty well and pretty safely.

Shares