How well has the private prison industry done, recently? As of a couple years ago, the fastest-growing airline in America was the non-commercial one that flew undocumented immigrants from one detention center to another. The deportation bubble meant boom times for the industry, which profited off fat contracts with the Department of Homeland Security.

Now, with the president’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program protecting nearly half a million DREAM kids, and flickers of hope for comprehensive immigration reform, that cash cow may be fading. Even without reform, calls to stay deportations are growing. Worse for the private prison industry, a persistently falling crime rate has led to a slightly smaller prison population in 2012 for the third consecutive year. The United States still incarcerates more people than any country on Earth, but a for-profit prison industry seeking constant growth should be alarmed by the numbers -- especially if the Justice Department really declares a cease-fire in the war on drugs.

But what do we do with struggling yet politically powerful industries in America? We bail them out, of course!

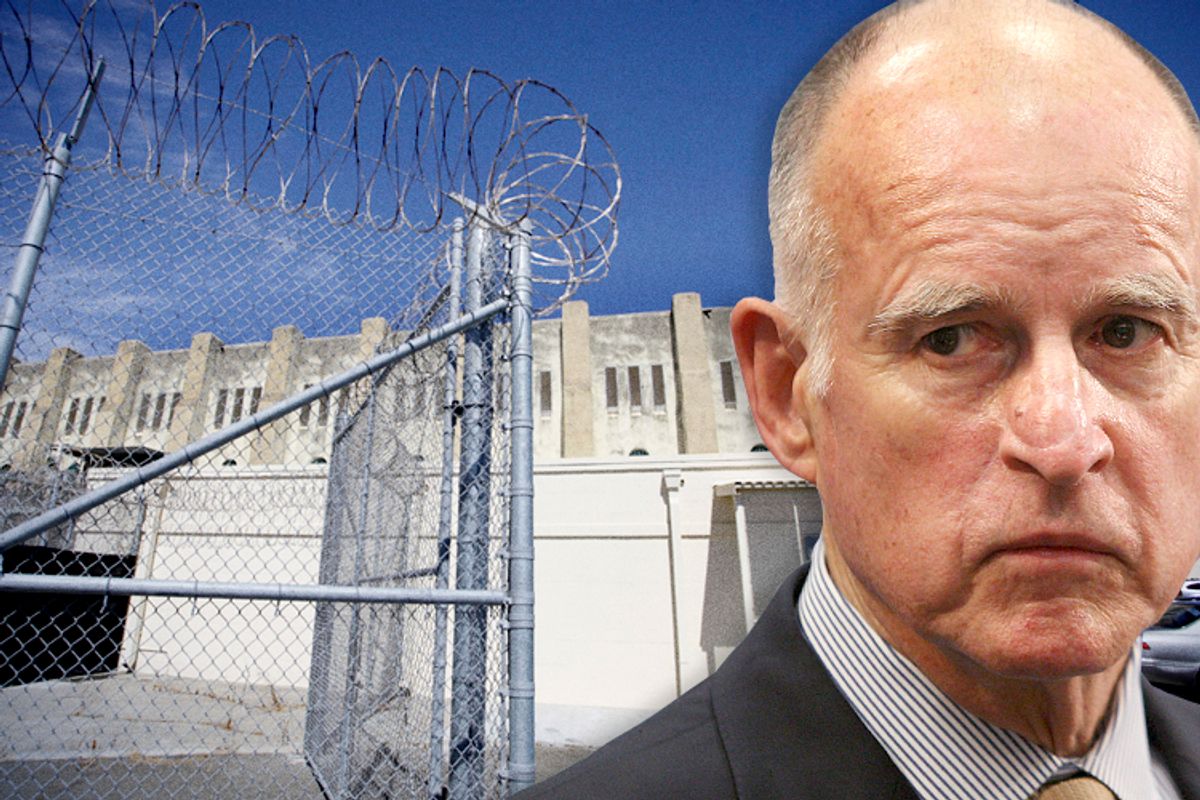

And California is set to do just that for the private prison industry. Under a Supreme Court order to reduce the prison population, Gov. Jerry Brown has outlined a plan where he would transfer thousands of prisoners to the for-profit system and pay them hundreds of millions in taxpayer dollars for the privilege.

The mandate to reduce the prison population in California dates back years. State officials have pursued a “Tough on Crime” posture since the white flight ushered in by inner-city riots in the 1960s, and the subsequent suburban sprawl. A 1976 law ended indeterminate judicial sentencing, and from 1978 to 2008, the Legislature passed over 1,000 sentencing laws, every one of them raising sentences.

These punitive measures, along with the “three strikes” law for repeat offenders and a twisted parole policy that fostered an extremely high recidivism rate (a 2008 federal report showed that two-thirds of all returning California prisoners came back due to technical parole violations like missing a meeting with their assigned case worker), led to massive overcrowding in state prisons. By 2010, the state had 170,000 prisoners and 85,000 beds, and was spending more on its prison system than higher education (mostly for overtime for prison guards). Extra bunks were stuffed into gyms and hallways. Riots were common.

In 2009, a three-judge panel ordered the state to reduce the population by 44,000 within two years, citing violations of the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the Eighth Amendment. In particular, the prison healthcare system was so burdened by overcrowding that one inmate was dying every week from lack of medical care. One convict waited so long for glaucoma treatment that his eye exploded. The healthcare system is now in federal receivership, but the overcrowding is the primary cause of this failure.

Governors from both parties have resisted this court order for four years, appealing all the way up to the Supreme Court, where the state lost. That’s right, a John Roberts-led Supreme Court told California it had to release thousands of prisoners to “prevent needless suffering and death,” and just last month, the Court held that the release could be delayed no more.

Attrition and partial compliance whittled down the mandatory release number to 10,000, mostly by transferring prisoners from state to county jails. Under this realignment plan, the counties, which had even less room in their lockups, were forced to release thousands of inmates before their sentences were up. But most important to the Legislature and the governor, they couldn’t be blamed for the aftermath. They are haunted by the ghost of Willie Horton, fearing 1988-style attack ads about an early release that led to a horrible crime.

But this is outdated thinking. States across the country have reformed their prison systems, taking a smarter approach focused on rehabilitation and treatment rather than mass incarceration. This has been a bipartisan movement, bringing together Democrats and Republicans in states as far-flung as Kansas and Georgia. But it has not filtered into California, where lawmakers are way behind the public in their fear-based Tough on Crime stance.

It’s not like there isn’t low-hanging fruit here. Low-level nonviolent drug offenders, who need medical help rather than a “violent crime college” like an overcrowded prison, litter the state system. Because of three strikes -- which mandates a life sentence after a third conviction -- California has the oldest prison population in America (5,000 are over age 60), including thousands of ill or infirm inmates, costing the state billions and taking up space in prisons. California has a medical parole system that hardly ever gets used. Not even a quadriplegic costing the state $625,000 a year to house in prison, when hospice care would cost pennies on the dollar, can get released. And just bringing sanity to the parole system would reduce recidivism and get the population down. The ACLU has cited medical parole and other ideas that would comply with the release order in a responsible way.

But Gov. Brown’s plan for “releasing” the final 10,000 prisoners by the end of the year involves transferring them all to private prison facilities, including one lockup in the Mojave Desert and several others out of state. California would pay for the transfer and the upkeep, costing the state $730 million over the next two years, eating up nearly 70 percent of the state’s reserve fund, money that could go to education or healthcare. This enormous expense represents life support for a private prison industry seeing a future growth lag. But if California keeps dropping off its excess prisoners, for-profit prisons have their own stimulus package.

Not every lawmaker in California endorses the governor’s approach. Senate President Darrell Steinberg described the plan as “throwing money down a rat hole.” But Steinberg’s own proposal hinges on seeking an extension from the court to release the prisoners over a three-year timeline. Steinberg also wants notable long-term reforms that would cap the prison population, and would give resources to local mental health and drug treatment programs. The lead plaintiff in the lawsuit that led to the mandatory reduction says he supports Steinberg’s extended timeline. But federal courts have rejected extensions and continuances time and again, so any plan predicated on another one is dicey.

With the State Assembly poised to approve the Brown proposal, the situation faces an uncertain resolution with two weeks left in the legislative session. But the choice here, between giving the for-profit prison system a financial windfall and hoping that judges reverse all their prior rulings and extend the overcrowding for three years, is not a good one. And by failing for years to reckon with counterproductive Tough on Crime policies, California has fallen well behind the rest of the country in devising a smarter and more effective system of incarceration.

The prisons are a mess; mass hunger strikes protesting widespread use of solitary confinement, a form of torture, speak to that. And Jerry Brown and his colleagues are too cowardly to stand with a growing cohort of policymakers who understand that we can invest in rehabilitation, drug treatment and deliberate reentry programs and have better outcomes, rather than revert back in fear to a “lock-’em-up” mentality that shortchanges taxpayers and rewards private prison executives, at no benefit to society.

Shares