The tenure system in American higher education is a limitless source of debate: Critics say it leaves younger scholars to publish or perish, or decaying professors to cash in on mediocrity; advocates note its importance in protecting academic freedom, risk-taking and, insofar as professors are workers, job security.

In Pennsylvania, it’s all moot. Now, under the stewardship of Jeb Bush’s former sidekick, tenured faculty are being laid off in droves. The response has been student sit-ins, faculty mobilization and investigations of Enron-style accounting. It’s a real-time, rolling image of higher education shock therapy — and a threatening signal to public universities nationwide.

Subject A: Edinboro University.

Edinboro, an 8,000-student campus in northwestern Pennsylvania, is one of 14 schools in the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education, or PASSHE. Last September, in the name of “strategic investment for the future vitality of the University,” president Julie Wollman announced that 42 teaching staff, including 18 tenured faculty, would be laid off, or “retrenched.”

“At first, the students were outraged,” says Crystal Folmar, a senior communications major — especially, she says, over the wholesale elimination of the school’s music program. One hundred and fifty students, faculty and staff rallied outside Cole Auditorium. Later, students delivered a 1,200 signature petition to the president’s office.

President Wollman wasn’t available, so they sat in. After a little over an hour, she emerged.

“I don’t think the reputation of Edinboro has to be damaged,” she said. “I think it will be damaged if the word goes out that this is a negative thing.” Because of state cuts, enrollment declines and hiring costs, she added, “we don’t need all the faculty members that we have.”

A student replied, “We have freshmen that are calling us, and on the 2018 Facebook that are asking, should we even come to Edinboro?”

“Well, the answer should be yes!”

Another asked, “Why are we spending so much money on buildings when we can’t pay the faculty?”

“The money has not come out of the general budget,” she said, echoing a common belief. “I think I’ve explained this a number of times. That’s incorrect. It’s true that in many states, there are two separate pots of money.”

The situation at Edinboro — layoffs, uproar, blithe financial entreaties — repeated itself at four other PASSHE schools. By the deadline for retrenchment notices, Clarion posted nine tenured layoffs, East Stroudsburg seven, Slippery Rock one, and Mansfield 22. Edinboro’s figure dropped to six, after the school decided to keep its music program. “It felt like a very political play the entire time,” Folmar says. “It was just a bait-and-switch.” After Mansfield pulled several names off its list, the total is now down to 34.

Still, as the plan stands, says Jean Jones, a professor of political science at Edinboro, “I think it’s going to impact enrollment. It’s all over the press here.” Moreover, “Exciting new young scholars would think twice about coming here to work. I think that applies to administrators as well.” Overall, she says, “Morale is terrible. People are depressed. The thing that worries me in the long term is that this is the new normal. It’s really just destroying the academic community. A number of faculty have told me that they’re just going to punch the clock.”

Why put all this — not just the promise of tenure, but the system’s culture and reputation — on the chopping block?

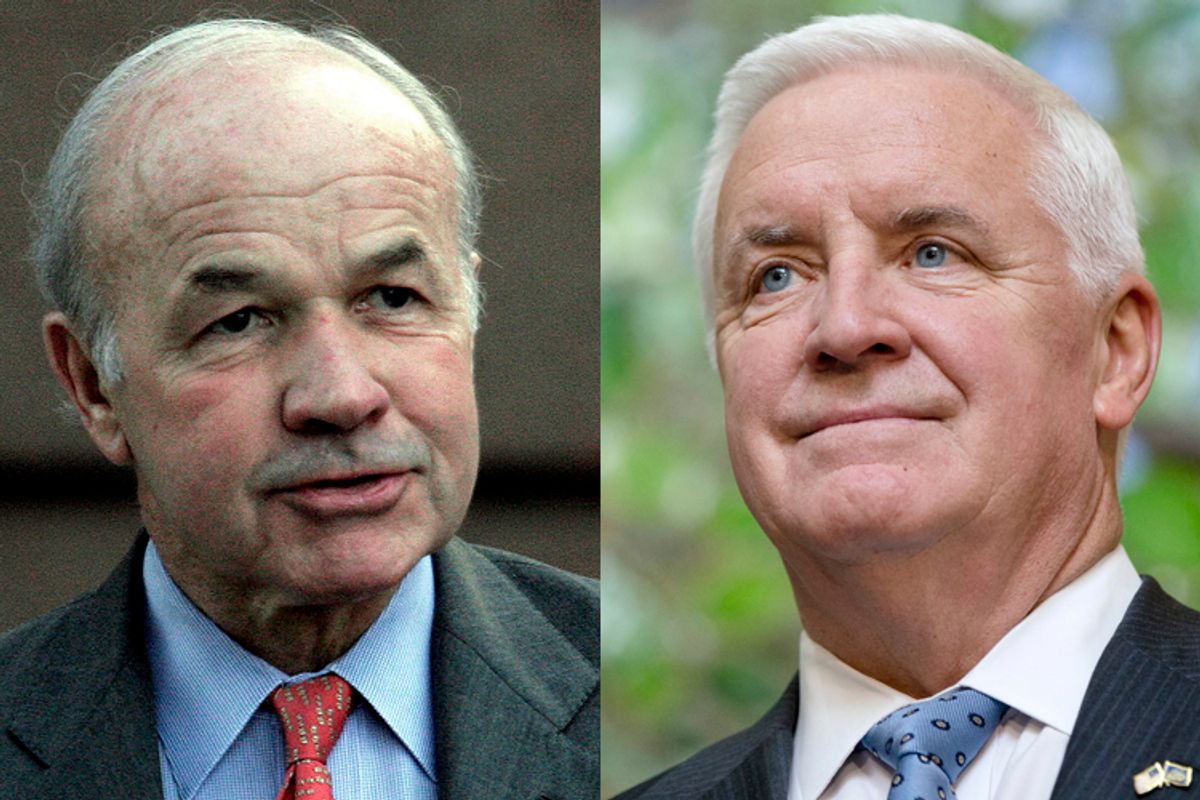

Part of it is the recession, which governments and universities have parlayed into austerity and privatization. Nationwide, state funding for higher education dropped 28 percent, or $2,353 per student, between 2008 and 2013, according to an analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. All but two states have cut spending during that time, and some, like California, Arizona and Louisiana, have seen hundreds of program and staff cuts. Some universities have merged; others have pursued taylorist schemes like shared services to attempt to reduce operational costs. In Pennsylvania, Gov. Tom Corbett, a sort of stealth Tea Partyer who rarely lets his persona overshadow his politics, proposed a 53 percent cut to higher education in 2011-2012 — which the Republican state Legislature whittled to a still-whopping 18 percent.

The academic slant of PASSHE’s cuts also falls in line with national trends — and Corbett’s own K-12 fiddling. In a system that began as a network of teacher training schools in the 1800s, arts, humanities and social sciences have given way to vocational training. The PASSHE retrenchment plans rolled out this fall ax not only professors in non-applied fields, but the majors, minors and certificates that they oversee. Over the last five years, the system phased out 158 academic programs while introducing 56 new ones in fields like software engineering, applied science and allied health. Likewise, the state’s 2012 Higher Education Modernization Act, unanimously backed by the Legislature and signed by the governor, supports programs in workforce-need areas like nursing and finance.

These trends are, in part, a function of tuition hikes — 23 percent in PASSHE schools since 2008-2009 — which disincentivize students from paying for non-applied coursework. With the additional influence of general enrollment declines, traditional programs are threatened with low demand. Those that remain face a vicious spiral: fewer course options, ballooning class sizes and, in turn, pedagogy that’s less personalized and degrees that are harder to obtain. And, of course, humanistic education is a right-wing bugaboo. As North Carolina’s conservative Pope Center put it, “One standard to use is whether a center, program, or institute serves and advocates for a political agenda. This is often the case in diversity or multicultural offices, women’s and ethnic studies centers and programs, and environmental programs.”

Retrenchment is another ballgame. Tenured faculty layoffs are rare, says Howard Bunsis, an accounting professor at Eastern Michigan University and collective bargaining chairman of the American Association of University Professionals. “Most [faculty contracts] have protections that say, before you lay off someone in this department, you have to make sure there’s no other work you can do.” And then, “Before layoffs happen, there has to be a declaration of financial exigency.” In the past few years, retrenchment has cropped up at the University of Louisiana and, in smaller quantities, within PASSHE. In 1977, the City University of New York, in addition to instituting tuition for the first time, went through a severe bout of retrenchment.

In Pennsylvania, administrators warn, it could become more common. “One of our concerns is that we might see this continue in the future,” says Lauren Gutshall, a spokesperson for the Association of Pennsylvania State College and University Faculties, or APSCUF. “Looking towards next year and the next two, three or five years, it’s likely that we’re going to see this battle come up again and again.”

In most cases, shedding faculty is simply a waiting game. Faculty may retire, or find jobs elsewhere, prompting nonrenewal of their tenure lines or replacement with adjuncts. Under these trends, the tenured or tenure-track professoriate plummeted from 57 percent of all college professors in 1975 to 31 percent in 2007. Retrenchment is a blunter device — a quick fix for universities crying exigency. On the flip side, it rolls back job security already in place, and an age-old academic tradition.

It’s also, in Pennsylvania, not the only possible fix. Down the rabbit hole, the system’s finances are an Enron-esque tangle.

As Kutztown University professor Kevin Mahoney details in the Pennsylvania-based Raging Chicken Press, under Democratic Gov. Ed Rendell’s administration, PASSHE began shifting its revenue model — and, arguably, its mission — to raising private funding through capital campaigns. This funding would go to “off-balance-sheet” entities, like campus-based foundations, to support new buildings, ranging from mall-like dorms to Edinboro’s sky bridge. While Edinboro’s president is right that capital budgets and operating budgets are usually separate, at PASSHE, universities began funneling money meant for education into these public-private entities to cover interest and principal on capital bonds. The upshot? Money that could be used to pay tenured faculty is helping fund student dorms.

Last month, APSCUF released an independent audit of the seven PASSHE schools that are, or at one point were considering, retrenching. The numbers aren’t pretty. The audit shows widespread discrepancies between universities’ budget projections — and, in turn, their ability to afford faculty salaries and benefits — and what their actual budgets turn out to be. At Edinboro, for example, they find an average yearly over-budgeting of $1 million in faculty salaries and $1 million in benefits between 2008-2009 and 2012-2013. “There’s a case to be made about why you do that,” Mahoney says, referring to conservative budgeting for personnel costs. “But what happens to the difference?”

While there’s no direct line between the money skimmed from salary and benefit discrepancies and increased revenues for capital projects, the auditors note that with operating costs in the black, “additional cash flow has been used for debt service and capital projects.” The high debt-to-equity ratio of these projects, they add, makes campuses riskier to invest in. Overall, they say, “Without strict oversight of these budgets, University management should be extremely cautious when utilizing these budgets to project faculty and other personnel retrenchment in 2013/14 and forward.” As Jones contends, “They’re not very good at budgeting. Given that your budgets didn’t match up with your actuals for the past five years, what are the implications for this year?”

Asked what kind of influence off-balance-sheet budgeting has had on university policy, PASSHE spokesperson Kenn Marshall says, “None. We don’t believe the report accurately reflects the situation on the campuses.” He points to chancellor Frank Brogan’s response to the audit, which cites “obvious errors” and states, “Tuition dollars and PASSHE’s annual state appropriation are not used to fund student housing, nor any other auxiliary operation.”

In general, the system’s attitude toward retrenchment is lukewarm. “These were extraordinary circumstances that our universities are dealing with,” Marshall says. “It was unfortunate but necessary.” As Brogan affirmed at a Kutztown meeting last month, “We are not, nor should we ever become, gigantic vocational, technical facilities. That balanced approach is what separates us from so many other educational delivery systems.”

So goes the neoliberal university: managers intent on reinventing the system by any means necessary, and rank-and-file stakeholders — staff, students, prospective students — catered a “balanced approach” that increasingly slants away from comprehensive education and transparent governance.

And who better than chancellor Brogan to shepherd PASSHE into the new normal?

In August, Brogan came to Harrisburg after two decades of state office in Florida. As commissioner of education, and then as lieutenant governor under Jeb Bush, Mahoney details, Brogan became a leading figure in the marketization of public education — helping Florida become one of two states earning as high as a B- on Michelle Rhee’s ledger. Meanwhile, he helmed the Education Leaders Council, founded in 1995 to lobby for privatization-friendly reform. And in 2001, President George W. Bush appointed him to his 31-person education advisory team. Guido Pichini, the chairman of PASSHE’s Board of Governors, who selected Brogan, has a record to match: His security company, Security Guards Inc., has made upward of $4.5 million from outsourced PASSHE services; as a Heritage Foundation Associate, his contributions to right-wing causes top $10,000.

This year’s retrenchment warnings predate Brogan’s tenure at PASSHE, so it’s unclear what role, if any, he played in the final calculations. “Each of the universities spent a lot of time developing workforce plans, looking at enrollments,” Marshall says. “They met with various campus groups. They worked on an individual campus-by-campus basis.” Still, as the campus-by-campus saga unfolds, Brogan seems intent on realizing the system’s makeover. “Make no doubt about it,” he said, at an Oct. 10 media briefing, “retrenchment is here.”

The opposition is moving in fits and starts. Last March, PASSHE faculty emerged from a contentious two-year-long contract fight, in which the system sought increases in temporary faculty and a variety of other workforce cuts. (The fruits of that fight, including retroactive raises, are often cited by administrators as an impetus for further cuts.) “We just literally signed the contract,” Jones says. “We haven’t stopped.” And yet, “This is, for the local campus, far worse than the negotiations. This is, we’re fighting with our local admins — and it’s much more real and close and personal.” In November, APSCUF hired three staff organizers to help with the mobilization, as campus-based union heads only get partial release time from teaching. While students and staff have assembled for rallies and speakouts across the state, activists register creeping burnout — and, for faculty on the retrenchment line, fear.

By March 1 of this year, first-year tenure-track faculty could still be targeted for cuts. As the spring approaches, the union will attempt to negotiate the remaining retrenchments off the table, continuing to press alternative pathways for raising revenue and tightening operations. It has also commissioned an additional audit for the remaining seven PASSHE schools. For its part, PASSHE’s Board of Governors is requesting a 4 percent infusion in base funding from the state and a one-time $18 million check to fund new programs.

As Mahoney argues, the fight isn’t just to save jobs, but to stave off no-alternative defeatism. “It’s the narrative that constantly gets reported again and again that becomes common sense: ‘Higher education is facing difficult times. Everybody is struggling back and forth, feeling bad, and there’s nothing we can do.’ If that’s as far as you’re going to dig into the reporting, you’re going to lose higher ed.”

Shares