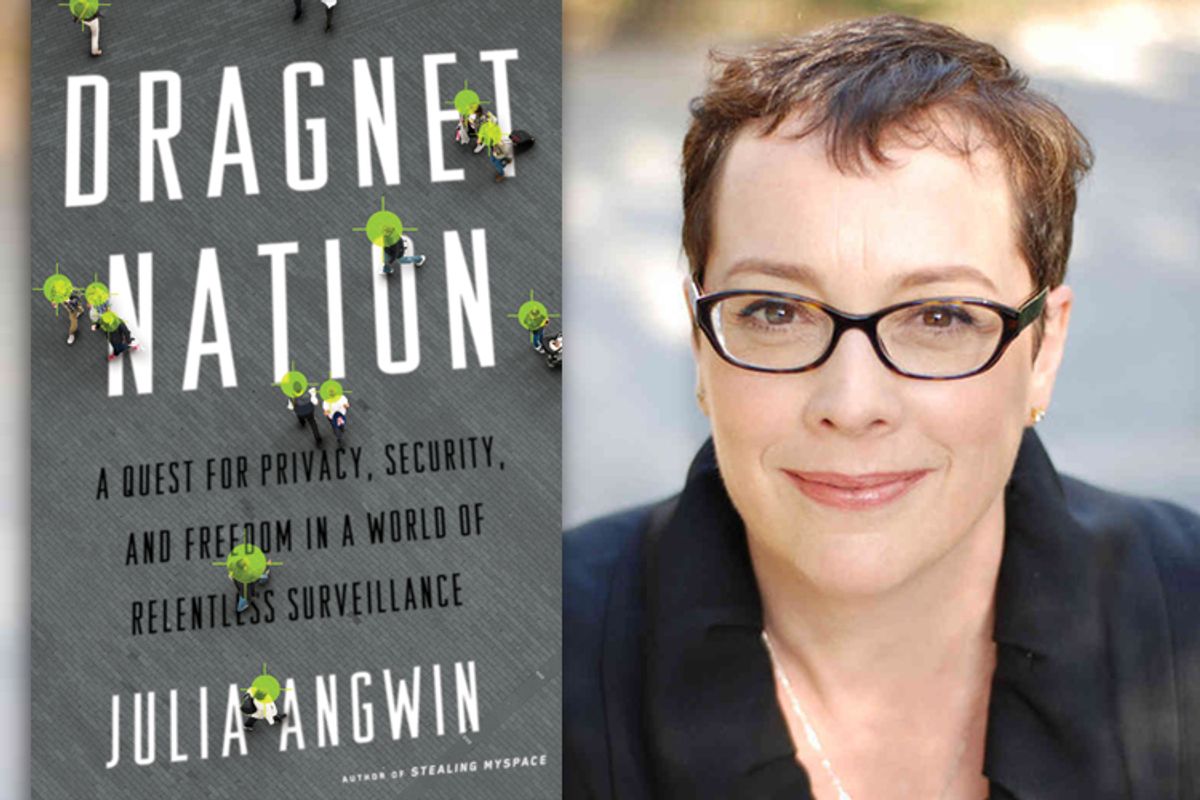

Julia Angwin might want to cut Edward Snowden some royalty checks. As a reporter for the Wall Street Journal from 2000 to 2013, Angwin reported for years about the intersection of privacy and new technology. She began work on "Dragnet Nation: A Quest for Privacy, Security, and Freedom in a World of Relentless Surveillance" long before Snowden began shocking the world with his leaked tales of NSA surveillance. But the timing of the publication of her new book couldn't have ended up being more propitious. At a moment when, largely due to Snowden's efforts, public interest in and concern over privacy issues is at an all-time high, Angwin has arrived with a deeply researched book that is completely of the moment.

"Dragnet Nation" moves right to the top of the list of books we should all read about privacy, because it goes beyond simply reporting, in detail, the sheer extent of both government and corporate surveillance. If you're looking for a comprehensible digest of the Snowden revelations and how they plug into our new world of Big Data and ubiquitous tracking, you'll get plenty of that. But the word "quest" in the title has a specific meaning. A hefty portion of "Dragnet Nation" is devoted to Angwin's efforts to escape the Panopticon. It's an impressive and intimidating saga that serves to highlight not only how difficult it is to maintain one's privacy, but just how essential it is that, as a society, we make it easier to do so.

Angwin spoke to Salon from New York, where she is now on the staff of the nonprofit investigative journalism outfit ProPublica.

Why did you write this book?

I've been on this beat for four years. I wrote the book because I felt that all my stories were really scary -- they are tracking you here, they are tracking you there -- but they weren't actionable; in other words, people couldn't figure out what to do about it. I was hopeful a book could provide some advice.

What was it like to be working on the book when the Snowden bombshells started to fall?

I still remember where was I standing when the first Snowden revelation about the Verizon secret order for the phone dragnet came out. My whole world was just turned upside down. I had been chasing that story because I had heard that that it was true. A lot of people that followed this issue had suspected it was going on, but no one had ever seen the proof. It was just mindboggling to see how vast it was. And then what happened after that, the continual flow, I mean even to this day, every week, there has been a new revelation.

You have a great quote early on in the book from when you go to visit the archives of the East German secret police -- the infamous Stasi. You describe to the director of the archive the extent of current U.S. government surveillance capabilities and he says "the Stasi would have loved this." What does it say about contemporary society that our level of surveillance would have stunned one of history's most notorious police states?

I think it is something that we really have to grapple with. When I went to the Stasi archives I found that they actually only had files on a quarter of the population and it took a lot of work and a lot of human effort to generate those files. They certainly had a population that lived in fear of the secret police, but the Stasi didn't have files on everyone.

Now we're in a situation where it is pretty easy for a government to have basically total coverage of their population. So that raises the question: What safeguards do we need to put into place so that these powers are not abused? Because there is no question that they can be abused. We are going to have to readjust our governmental oversight to make sure our government doesn't become a repressive regime. It currently is not. But the architecture is there.

How did we get here?

I trace our current world of dragnets and ubiquitous surveillance back to 2001 in two directions. First, after 9/11 the government got really interested in increasing surveillance capabilities, for a very obvious and legitimate reason -- they had missed the attack. At the same time Silicon Valley woke up and said "Oh my gosh our business model isn't working." The dot-com bubble had burst. Both Silicon Valley and the government had a problem and they both came to the similar conclusion that the answer was collecting vast amounts of personal data. From the commercial side it turned out that the way to get advertisers interested in the Internet was to offer them incredible insights on the people that they were advertising against. And on the government side it was: If we collect a lot of information we can find these terrorists.

Unfortunately, what we've seen is these two things converge. The companies collecting information -- like Google and Facebook -- have discovered that they can't easily say no to a court order saying give me the data, and we've also learned that sometimes the government hacks into commercial databases when they are officially blocked. Commercial data has become a honeypot that government likes to dip its hand into.

Are attitudes changing about privacy?

I think that the Snowden revelations have made it clear how intertwined government and commercial surveillance are. Before, maybe it wasn't as obvious to people that the information that Google had accumulated was also being accessed by the government. Even though we knew it theoretically, there's something really different about seeing these slides from the NSA with the little smiley faces about how great it is to get Google data.

The majority of your book is about your own personal efforts to ward off surveillance. You go to amazing lengths to escape the trackers. You create a false identity, you opt out of everything possible, you even leave Google!

I know! It was like jumping off a cliff.

But it doesn’t seem to work. You don't end up escaping the trackers.

Yeah, I would say that I was at best 50 percent successful, and that's probably an optimistic number. But I felt like it was still a worthwhile exercise because what I learned was that some things were pretty easy to do and very rewarding and other things were almost impossible. So this gave me a better sense of the fact that I did have some control. And that's important, because I don't think it's helpful for everyone to sit around and feel hopeless about this subject. I wanted to look for hope. "Dragnet Nation" is investigative journalism for whether there is any hope.

What I found is you could do this, you could do that, and maybe some of these other things are a little too hard. But maybe by raising the fact that these things are too hard I might help find a solution for them.

What does your investigation reveal about the current state of the marketplace? If people really care about privacy, shouldn't entrepreneurs be providing us with secure alternatives?

I think that we are at an early stage. Most people probably didn't think much about privacy until the Snowden stuff came out. I think we are just now starting to see the true cost of all the free services we pay for. Because they are not free. We pay in different ways. Some people are going to be OK with the tradeoffs, but I think as we learn more about how much information we are giving up for these services, there will be an emerging market of people who are willing to pay for different types of services.

You make clear early on that privacy is inextricable from power. Can you give some examples?

Information is power. If you're in negotiation about something, like buying a car, you certainly don't want the car salesman to know everything about you: your income, your willingness to pay, how many other dealerships you've already been to that day. We engage in such negotiations all the time -- we are negotiating the terms of our relationship with the government, with our doctors and our schools and the places that we shop. If they all know everything about us before we even step in the door, our ability to have any leverage in that discussion is diminished.

The day is not that far away when you will walk into a store and the facial recognition will be good enough that the store could pull up your date of birth on your file with your income and your property ownership and offer you deals according to what they think you can pay. I think we want to decide if that's a world we want to live in. Do we want to be in the position where the companies have all the information, where we're in an arms race with them but they have all the ammunition?

Is this something that ultimately can only be decided politically? Is that even feasible?

I think it is. I think you are right to say that I am probably too optimistic. I am aware that I take a slightly irrationally optimistic view of this. But I also think that the only way to get change is to be irrationally optimistic. Change happens all the time. I compare privacy to environmental damage. We lived in a world where we were perfectly willing to tolerate our rivers catching fire and the air being filled with soot and people dying of black lung disease and then all of a sudden, after 50 years of that, we decided maybe we don't want that kind of world. And we've been very successful at cleaning up our environment. We did it partly through laws, but we also did it by changing our social norms. I mean if you told someone 50 years ago that Upper East Side women in fur would be picking up their dog's poop, they would have laughed at you. But we did it, we changed our social habits. I think privacy is a similar social problem. It's something that we will change both through laws and also through being smart about what choices we make about what technology we use.

Shares