The gap between the rich and the rest is better described as a canyon, and it's only getting worse. The economy no longer delivers for the average worker, having been rigged to benefit entrenched, wealthy interests. Millions of Americans are losing their livelihoods to technological progress and capital's access to a huge pool of cheap labor. And any attempt to solve any of these problems is met with an iron wall of resistance from a Republican Party at war with itself but nevertheless slavishly devoted to corporate interests and a failing status quo.

That's one way to describe America today. It's a way to describe America 100 years ago, too. As the proverb goes, "There is nothing new under the sun." (Or if you're more of a modernist...)

Yet just because we've been in this situation before doesn't mean we're doomed to be stuck in it forever. At least not according to author and historian Michael Wolraich, whose brand new book, "Unreasonable Men: Theodore Roosevelt and the Republican Rebels Who Created Progressive Politics," examines American politics in the early 20th century, during the tumultuous period when the Gilded Age was not yet past and the Progressive Era was not quite present. While the parallels linking that time to our own may be cause for despair, Wolraich shows how fearless progressive politicians and activists were able to overcome the many barriers to a better society and usher in an epoch of then-unprecedented reform.

Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

What inspired you to write this book? Why look look so closely at this era of U.S. history?

The idea for the book started off fairly simply. There was, several years ago ... a resurgence of interests ... and concern about economics and economic inequality and corporate influence on government ... Particularly back during Occupy Wall Street protests, there was a lot of rhetoric that mimicked the rhetoric of the early progressive movements; the criticisms of Wall Street and corporate control and the whole 99 percent echoed class arguments that Democrats hadn’t really emphasized for a long time. And what struck me was that many of the people who were employing these arguments really had little sense of where they came from and where they started. There’s a fair amount of understanding and recognition and appreciation for FDR and the mid-twentieth century. But in talking to people, both in the protests and the blogosphere, I just get the sense that people don't really know how progressivism started.

So my original idea was just to write a book, partly for the left, partly for the country as a whole, to remind us of how that movement started, why we have a lot of the progressive laws that were passed in the first place and why it’s important today. Then just as a follow-up, as I was digging into it, figuring out what exactly I was going to write about and I started moving towards Robert M. La Follette, one of the early progressive leaders from Wisconsin, and I was fascinated with his relationship with Theodore Roosevelt, which I had only a broad understanding of before I started to write the book. I was fascinated by the story and fascinated about what it can teach us about politics today.

Let’s talk about those two guys, not only their personalities but what you feel they embodied at the time and what they still represent today. Start with the one that I'm sure people have heard less about, Robert M. La Follette. What’s his story and what about him do you think is so interesting and relevant to today?

La Follette was governor of Wisconsin. Well, he was originally a congressman and then governor of Wisconsin, and then ran for senator of Wisconsin. He was a lifelong Republican but he was very critical about the practices and ideology of the Republican Party at the time. You could call the Party conservative — they didn’t really use that terminology at the time — but he had ideas about progressive reform that were shut down. He was particularly upset with the corruption that was endemic to both parties. There was a lot of corporate influence and old-school bribes. A lot of it was very similar to today where corporations would fund political campaigns and then politicians once elected would do favors for their benefactors.

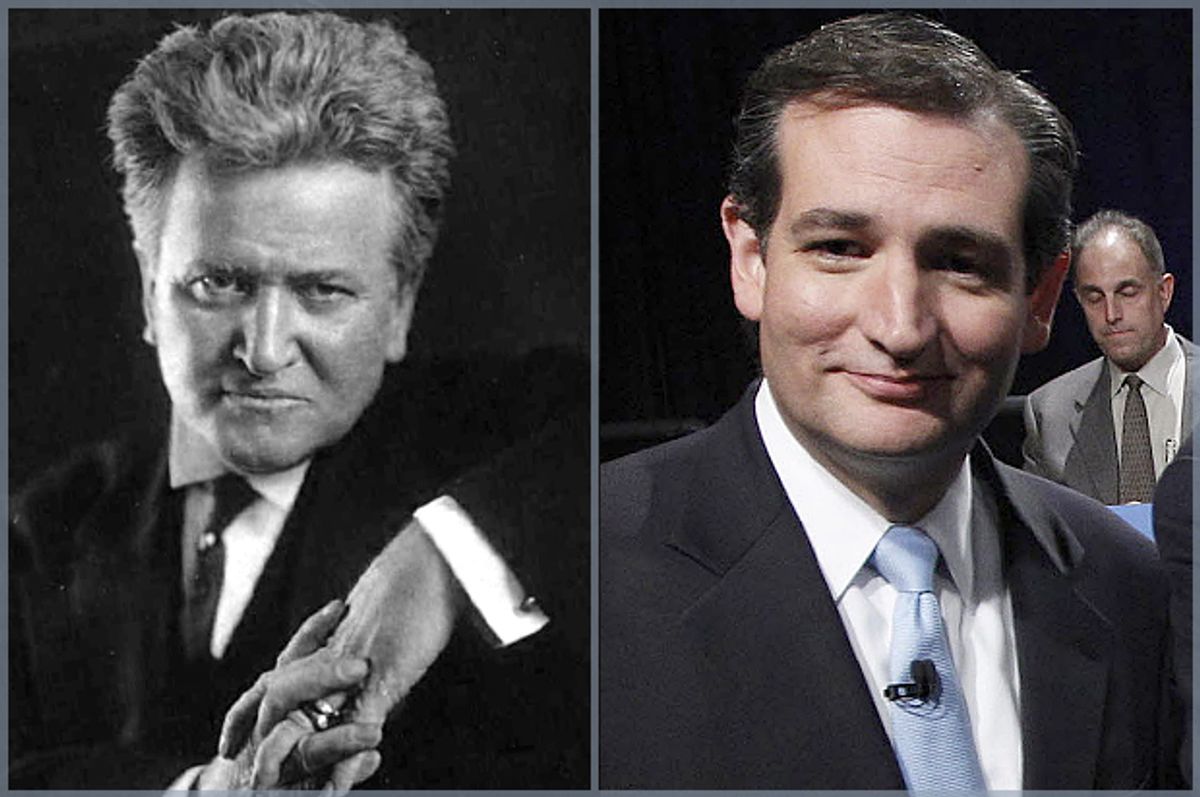

La Follette decided to lead a fight against this. And he was shut down by the state Republican Party in Wisconsin. So he mounted an insurgency against them. He was a very eloquent and inspirational public speaker and he went around the state talking about the power of the corporations, particularly the railroad corporations, and the corruption in the Party. He ran three campaigns for governor before he finally won. Then [he] had another fight the next four years where his progressive insurgents — they called them “half-breeds” at the time — took over the state party. He was in many ways the Ted Cruz of his day, particularly when he got to the Senate. He mounted primary challenges against fellow Republicans. He did sensational filibusters Roosevelt regarded as pointless. He refused to compromise. I’d say he was the mirror image of Ted Cruz because he was arguing not for conservative ideology, but progressive ideology.

Who constituted La Follette's "base"? Cruz has the Tea Party — mostly a group of older-than-average and richer-than-average white people, many of whom could be called petty bourgeois because they own their own small businesses or property. Who did La Follette have?

La Follette’s base was very rural. It was farmers, small accounts people, people who felt at the mercy of East Coast elites, as they thought of them. There was, to a growing extent, laborers in the cities [that] became a part of his base. ... He would speak often about the “common man.” That was his base. That’s who he spoke to. That’s who drove his movement.

You mentioned that he had to run three times before winning the governorship in Wisconsin. What changed in the state between his first and second runs and his eventually successful third attempt?

During the early progressive movements, many people — even Woodrow Wilson, who had been more conservative almost until he ran for election — they often use the word awakening [to explain their embrace of progressivism]. La Follette very much saw himself as an educator, and he would help voters to understand the problems that were happening in the country and understand they could, by mobilizing, fix the problems with government that were preventing reform legislation from advancing the country forward.

Was it similar to what's happening in the country right now with regard to inequality? Some cataclysmic event made people realize that whatever they were doing for the past, say, 20 years wasn't working anymore?

I would say it was more that people found an explanation for what they had been struggling through for the past three decades of the Gilded Age. La Follette would talk about the ways in which corporations influenced government at the expense of the people he was appealing to. He would expose the ways of the railroad companies’ favored giant trusts like Rockerfeller’s Standard Oil Company. [He would] talk about a corrupt tariff system. For the income tax, that was the primary means of revenue. He would talk about how the tariff system was, in contemporary terms, a regressive tax and talk about how it would put the financial burden on people to the advantage of corporations that benefited from the tariffs.

For people who don’t know, the Gilded Age — especially the late stages of it — was a period with a lot of financial instability, right?

Yes. Every decade or so there would be a [banking] "panic" ... There would be a currency shortage because there was no central bank or Federal Reserve to manage the currency supply and the money would become tight, literally cash would become tight; companies would pay their employees in nickels or vouchers because they didn’t have the cash on-hand to pay them. That would spark bank runs and the whole economy would collapse. In 1893, and then again in 1907, that shock propelled what was already becoming a national movement into the mainstream.

Let's turn to Teddy Roosevelt. How do you understand him, how was he seen during his era, and how did he differ from La Follette?

I think people’s understanding of Teddy Roosevelt today is interesting. His legend has eclipsed him. We sort of understand his celebrity. We understand his force of personality. But most people don’t really understand much about what he was actually doing, what his goals were and what his actual tactics were. So one thing people might not expect is that you think of Roosevelt as being this fighter, which in some ways he was. But he was also a tremendous compromiser. He even wrote an essay praising compromise and how important it was. He thought of himself as a very practical man. ... He was a reformer. Usually, if he wanted to pass some bill that his Republican colleagues in Congress did not want to pass, he would size up the opposition, figure out the best bill that he thought he would get through, and then he would push that bill. Oftentimes he got a fight, and then he would negotiate [with] them to get to pass whatever he thought he could be accomplished. This was very different from La Follette’s approach, who would never compromise and believed that to pass “half a loaf,” as he called it, was counterproductive.

If Roosevelt was such a pragmatic, incrementalist actor while president, then how come we remember him as this pugnacious and irascible brawler? What changed?

I think two factors: One, he was very militant. ... He was one of the most prominent supporters of military intervention in World War I. ... Also, a lot of his rhetoric is about fighting. He thought of himself as a fighter, but a practical fighter. I find his famous quote “Speak softly, and carry a big stick” is a little bit ironic, because oftentimes he would speak very loudly and carry a relatively small stick.

If you had to compare him to somebody in contemporary politics do you think there's an analog today? If so, who would it be? I tend to associate him with John McCain, because of the militarism but also just because McCain's said before that Teddy Roosevelt's his favorite president.

I like your John McCain analogy in terms of his foreign policy. In terms of his domestic policy, I think there’s certainly an interesting analogy to Obama. Not in the sense of his personality or his rhetoric, but in his approach to politics. I’m thinking about the way Obama dealt with some of his budget negotiations with the Republicans, the way he dealt with the failed gun control legislation. He very much sizes up what can be accomplished and does not try to accomplish more than he thinks he can achieve. You don’t see Obama pushing bills that aren’t going to pass. He sees no point in wasting time on that.

The other element of Roosevelt that might invite comparison to Bill Clinton is Roosevelt thought of himself very much a man in the middle. He was trying to balance, for much of his presidency, between the conservatives on one side and the progressive reformers on the other. And you'd see it in the speeches: He would rail against corporations and party bosses, and [then] he would complain about demagogues and radicals and zealots. So this idea of balance is very important to him throughout his presidency.

Now, another reason people think of him as a fighter is that changed after he left office. He went off to Africa and Europe for a year and a half and by that time the progressive movement that La Follette was leading was flourishing. And Roosevelt jumped on board in a way he never had during his presidency. Ultimately he did what he previously had attacked La Follette for doing, which was split with his own party and went on to found the "Bull Moose Party," which was the the nickname for what was called the Progressive Party.

I think that can take us to a really central conversation that your book engages with and I think will inspire: the tension between the two approaches, with Roosevelt's pragmatism on one side and La Follette's absolutism on the other. Why do you think Roosevelt eventually moved to La Follette's side? Was it about character or was it structural, having to do with his no longer being president and thus having different opportunities and constraints?

In the book, I talk about two reasons for his shift, one of which you hit on the head, which is he wasn’t president anymore. He was, as president, very concerned with what legislation he was going to pass during his presidency. He was always very focused on his legacy and on accomplishing something while in office. So given the choice of passing a weak bill or no bill he would always go with the weak bill and proudly trumpet what a great bill it was because he saw that as better than the alternative. Some of his critics ... accused him of never really looking beyond the next battle. After his presidency, when he was not in office and was not initially running for reelection, he was free of that. He looked beyond the horizon and was able to think about not just the next battle, but the entire war.

The other factor is that Roosevelt had a very intuitive sense of public sentiment. Sometimes, without even knowing it, he would adjust his ideas and his posture and his rhetoric in a way that perfectly captured what was resonating out in the country. When he came into office there was a fledgling progressive movement but it was still very muted; by the time he returned from Europe [after his presidency], the entire country was moving towards progressivism. I don’t think Roosevelt calculated that. I think he felt it. I think he embodied it and moved from his central position of his presidency.

What was the progressive press's relationship with Roosevelt like? Was it similar to the one the left has had throughout the Obama presidency, with palpable frustration never quite reaching the point of (seriously) considering abandonment? Was there a similar kind of love-hate relationship over Roosevelt's acceptance of half-measures; or did the progressives ultimately end up seeing him as one of their own?

Most journalists loved Roosevelt. It was hard not to love Roosevelt just because he had such a big personality. He was so much fun to cover. He gave them such great access. So everyone liked Roosevelt, the man. He had a very interesting relationship with some of the more progressive journalists like Lincoln Stephens or Ray Standard Baker, who he had very close relationships to.

But I would say as the progressive movement developed and as they started to move more and more to the left faster than Roosevelt was, there was some disillusionment that occurred. [Progressive journalists] still considered him a good friend, because they were actually still quite personally close with him, but they became increasingly disappointed with his follow-through — not so much his policies but his execution of his policies. They were frustrated with his compromises.

Both Baker and Lincoln Stephens — who were among the leading muckraking journalists of the era and really pioneered investigative journalism — both eventually gravitated towards La Follette, much to Roosevelt’s dismay. And they would pester him. They would say “La Follette did this, La Follette did that," and it drove Roosevelt crazy.

So where do you, personally, end up in terms of picking a side between La Follette on the one hand and Roosevelt on the other? Who do you think was right at the time and who do you think would be right in our present time?

I’m definitely siding with La Follette’s approach in this context. That doesn’t mean it’s necessarily right in every moment. But I think that it particularly applies when you have a determined, obstructionist opponent, as they had then. The conservatives at the time were determined not to let any serious legislation through, and they would either rebuff Roosevelt’s efforts or, very often, emasculate them. So what he accomplished, the incremental reforms that he accomplished, were actually very modest in significantly addressing the problems and conditions of the time.

What La Follette saw was that change was never really going to happen unless you actually reformed — revolutionized, even — the political order. And you really had to create a more democratic political system; you really had to get people who were blocking change out of Congress, and anything you tried to do while they were in office was doomed to failure. I do think that in our current political situation, that there are a lot of parallels to that. That attempts that Obama and Democrats have made to try to compromise with weak bills — and I mentioned the gun control bill before, which even if it had passed, would not really have done much —

Right, it was so weak as to be nearly symbolic.

Exactly. And [for Democrats] to say, "Well, we got something done!" I don’t think that approach works. I don’t think the Republicans at this time are negotiating in good faith. I don’t think they want to pass, or are willing to pass, anything that Democrats believe is important. So to improve the situation, I would say the left and Democrats need to pivot and stop focusing on passing whatever bills they can get through, and look into really changing public sentiment. Really changing the long-term trajectory that went on and work on, right now, on persuading the country of their vision and agenda, rather than trying to squeak through whatever they can.

Shares