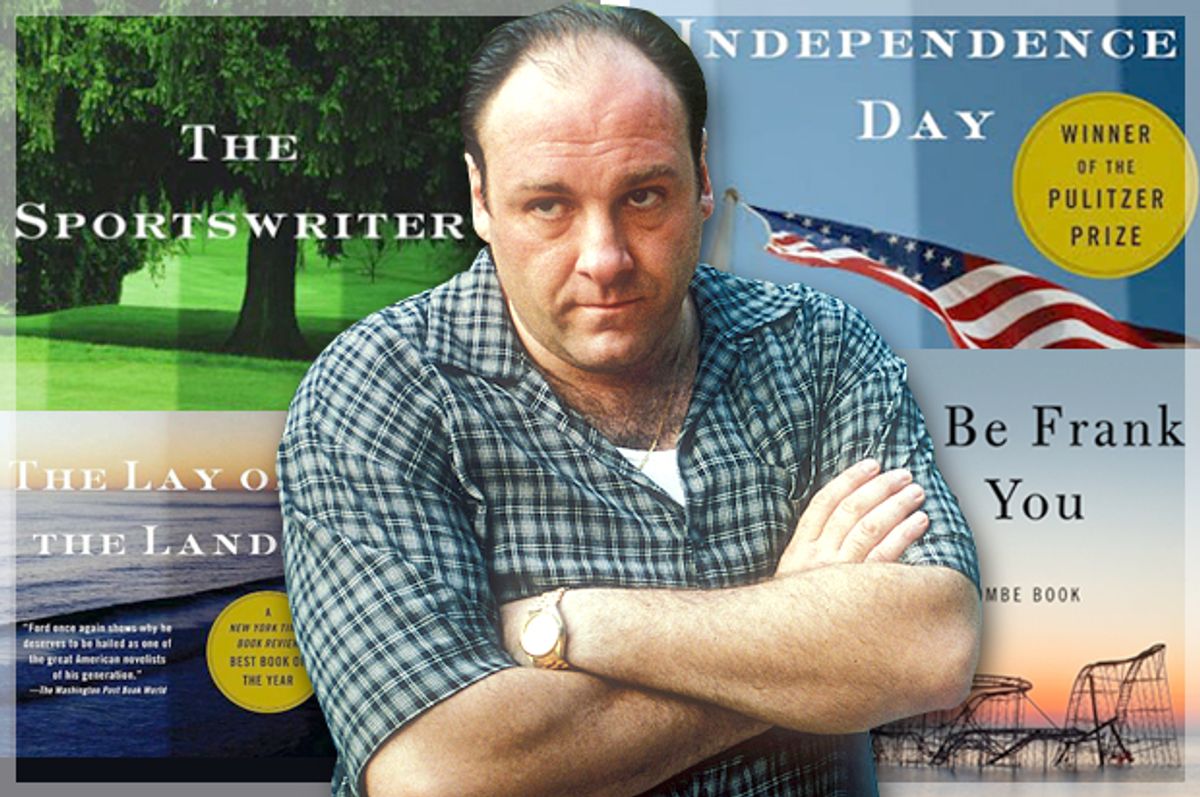

In early 2013, Richard Ford gave a reading in New York City during which his great protagonist Frank Bascombe — the writer-turned-realtor of “The Sportswriter,” “Independence Day” and “The Lay of the Land” — resurfaced after an absence of seven years. Bascombe’s reappearance thrilled his fans, although Ford, according to the columnist John Williams, did not plan at that juncture to bring Bascombe out of retirement for any big project. But then, suddenly, the word came that Frank Bascombe would appear in a new book, one titled like the ghost-written autobiography of a talk-show host of yesteryear.

A few months ago, another fictional hero was resurrected. In a Vox profile that launched a thousand refutations and reassessments, the writer David Chase seemed to reveal the fate of Tony Soprano, whose screen career ended in 2007 (just a year after the final novel in the Bascombe trilogy was published). Asked whether Tony was dead, Chase was alleged to say, “No. No, he isn’t” (and then promptly disputed the implications of this already cryptic remark). For a moment, optimistic people got to imagine Tony cruising around New Jersey — age 55, kids grown, looking at life from the tail end of a second Obama presidency. There is no way to predict, exactly, what the landscape of a life like Tony’s might look like seven years down the line — a life punctuated by violence both random and calculated, a life of varied occupations, characterized by emotional storms, fractious family living, and a parade of women (some constant, others less so). It’s difficult to imagine that Tony would be alive at all, given the state of his affairs when the curtain closed in 2007.

Now “Let Me Be Frank With You,” Richard Ford’s unexpected continuation of a beloved franchise, offers a satisfaction that will undoubtedly elude Tony Soprano’s fans (David Chase is famously grumpy about his masterpiece and inclined to refer to the show as an incidental thing that prevented him from doing other, better things). When last we knew Frank Bascombe, he was 55, living in what he called the “Permanence Period” of a man’s life (the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Independence Day” documented the murkier “Existence Period”). And yet a period that should have been defined by the stolidity of middle age is marred by prostate cancer, an errant second wife, and aberrations that track from the generally ominous to the Frank-specific: a hospital bombing, a brick through a window, and finally, two gunshot wounds to the chest, sustained during a robbery that kills Frank’s neighbors in the seaside Jersey town of Sea-Clift.

Closing out “The Lay of the Land” in 2006, it was likewise hard to imagine what the lay of the land in 2014 might be. In fact, it was no less difficult to imagine today’s Frank Bascombe than a resurrected Tony Soprano: Frank was always a man that things just seemed to happen to; often, they were not good. His woman situation alone, fluid over three novels, was impossible to forecast; he travels from first wife and mother of his children Ann Dykstra, to the Dartmouth coed Catherine, to Vicki the buxom nurse, to the murdered Clare, to second wife Sally, who spends most of "The Lay of the Land” trying things on with her long-lost first husband, AWOL Wally. (Add to these the unnamed conquests and the incidental women who simply add frisson to Frank’s days — waitresses, bartenders, even his children’s respective female love interests — and there’s just no telling.)

After the tumult of the last Bascombe novel, Frank’s life in “Let Me Be Frank With You,” a collection of four linked novellas, is relatively placid. He’s 68, retired, married to Sally but cosmically linked to Ann, who is living in a posh care facility in the early stages of Parkinson’s. He is still inclined to philosophical reflection and a curious combination of low-level hysteria and a preternatural ability to take the long view. The first piece in the collection, “I’m Here,” opens with Frank “laying awake in the early sunlight and shadows, daydreaming about the possibility that somewhere, somehow, some good thing was going on that would soon affect me and make me happy, only I didn’t know it yet.”

For the most part, “Let Me Be Frank With You” allows Frank to live in this possibility. The bad things that happen in these novellas are happening to other people: Hurricane Sandy knocks over Frank’s house, but it’s no longer his house. Parkinson’s strikes Frank’s wife, but she’s no longer his wife. An act of brutality takes place in his new home, but it was decades ago, when it was someone else’s home, and someone else’s family. As Frank puts it, “There’s something to be said for a good no-nonsense hurricane, to bully life back into perspective. It’s always worthy of our notice when we don’t feel precisely the way we thought we would. Easy to say, of course, since I don’t live here anymore.” As the new owner of Frank’s beachfront house succinctly states, “Everything could be worse.” (This is also the title of the second piece in the collection.)

Frank is the same Frank, a fussing tax-and-spend liberal of the old school who has not yet absorbed enlightened racial attitudes but feels marginally absolved by the correctness of his politics in contrast to those of the Tea Partyers around him: “Ms. Pines was medium sized but substantial, with a shiny, kewpie-doll pretty face and skin of such lustrous, variegated browns, blacks, and maroons that any man or woman would’ve wished they were black for at least part of every day.” (Neither, though, is he totally ignorant of the problems with his views about race: “Almost all conversations between myself and African Americans devolve into this phony, race-neutral natter about making the world a better place, which we assume we’re doing just by being alive.”)

If anything, Frank seems to have slipped into a slightly premature dotage. He is 68, which in today’s America, for Americans who are lucky enough to be prosperous and disease free, should ostensibly be the new 58. Yet he frets about having an old-person smell, and worries about the “death sentence” of falling down, and sees the end of the line all around: “Once it was possible to cast my eye over almost any piece of settled landscape herearound and know how it would look in the future; what uses it’d be set to by succeeding waves of human purpose — as if a logic lay buried within, the genome of its later what’s-it. Though out here, now, all is frankly enigma.”

I happened to start watching “The Sopranos,” which I had never seen in its entirety, toward the end of the summer, shortly before David Chase said, “No, he isn’t,” and caused a riot. I worked my way through the Bascombe novels in September and October, so that when Journey played over the final credits of Chase’s creation, I was nearing the end of Ford’s. This timing obviously informs my sense that the lives of Frank Bascombe and Tony Soprano are full of surprising parallels.

But this correspondence aside, I can’t help seeing the debt that Chase owes to Ford — and likely the reverse — or simply the great spiritual overlap of these two emblems of American manhood. Frank may be a down-stater — a Southern-born, Big-Ten-attending, gin-drinking Anglo in weejuns, with an educated man’s tools for self-expression and navigating the world. But while Frank doesn’t share Tony’s ethnic background or profession or make Tony’s flavor of gaffes (“I was prostate with grief”), the fundamentals are there: Sudden storms of melancholy; panic attacks in suburbs and Suburbans; a seeming intrinsic kindheartedness that invites the uncomfortable confidences of closeted gay men, then gives over unexpectedly to pointless acts of hostility or revenge, sometimes sexually motivated and sometimes just ornery (like when Frank queers a real-estate deal for his employee, Mike, after an exasperating encounter with his own son — “This is purely punitive,” Frank admits). Like Tony, Frank gets drawn into random fistfights in bars, and attracts an amount of police interest over the course of the novels that would seem more fitting for a man in Tony’s line of work. Like Tony, Frank has portentous dreams; “tell a dream, lose a reader,” he once says in a piece of authorial cuteness, since Ford, like David Chase, never shies away from the narrative possibilities of dreams.

Both men have one overachieving daughter, who can’t seem to settle down to excelling at one thing, and one fuck-up son, the barometer on which swings from the pathological to the pitiable by the minute. Both men have an interest in history and a secret susceptibility to pedantry, with limited outlets for release. They hold decided views on race and class, expressed in varying levels of couth. Both lament the changing times: “What isn’t ignited by stress?” Frank asks, in the most recent book: “I didn’t know stress even existed in my twenties. What happened that brought it into our world? Where was it before? My guess is it was latent in what previous generations thought of as pleasure but has not transformed the whole psychic neighborhood.”

And yet even while they feel like holdouts from a previous age, Tony Soprano and Frank Bascombe are at the vanguard of something, whether that something is, as A.O. Scott contended, a devolution — the “end of male authority” — or a new way of living, or merely a new acknowledgment of something that’s always been true. After an afternoon with an old flame in the idyllic Berkshires, Frank concedes that he and Ann, like Tony and Carmela, were “finally too modern for this kind of perfect, crystallized life.” The strength of the two story lines is such that, concurrently reading the novels and watching the shows, I began to feel that all of American life was held in the small, densely populated state of New Jersey, and somewhat dismally, that all of American experience can somehow be explained by two affluent white men in big cars, and their now-oppositional, now-defensive postures against the world.

“The Sopranos” launched a streak of television that keeps commentators asking whether TV has supplanted the novel as the great narrative vehicle. Perhaps the pervasive effects of television have something to do with the loose novella structure of “Let Me Be Frank With You,” a significant departure from the long, densely foliaged novels that spun a couple of days into several hundred pages. The new work can, by comparison, feel sparse and aphoristic (“If there’s a spirit of one-ness in my b. ’45 generation, it’s that we all plan to be dead before the big shit train finds the station”). Or possibly this new format is a function of Frank Bascombe’s age, which, in his words, “explains more and more about me, like a master decryption code.” To put it in terms of Frank’s prostate, a main character in the last novel, maybe these novellas are an older man’s fitful pees, rather than the sustained stream of a younger man. But they are still full of wonderful words — adjectives like “bescroffled” — and vivid description. Frank Bascombe may be slower and more crotchety, but we still want to visit with him. Perhaps we will have another chance, before the screen cuts to black.

Shares