It’s Oct. 14, 2014, and I’m standing in a hotel conference room in Providence, Rhode Island. The room is filled with immunologists, microbiologists, virologists — people who study the things that make us sick, and what happens to us when we get sick. And most of them are more worried about flu than Ebola.

Dr. Annie De Groot, convener of the 8th Annual Vaccine Renaissance Conference -- also director of the University of Rhode Island’s Institute for Immunology and Informatics, and founder and scientific director of the GAIA Vaccine Foundation (an NGO working toward HIV prevention in Mali) -- can’t wait to go back to West Africa. She just has to convince her family. Eliza Squibb, GAIA’s executive director, nods in assent. Both women look wistful, and a little pissed off.

The United States of America is two days into the diagnosis of Nina Pham, the nurse who contracted Ebola while caring for Thomas Eric Duncan in a Dallas hospital. When I woke up yesterday morning, Pham’s diagnosis was being subjected to incantation by newscasters on all the cable news channels:

Do we know if Ebola is airborne? Do you support the closing of U.S. borders? Will this issue be used politically in the upcoming elections? What went wrong?

By the time I got downstairs to get my name badge for the conference, there were two local affiliates interviewing people about Ebola vaccines. De Groot had been working on one for the past five years, and a U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases researcher named Les Dupuy told the cameras that scientists were trying to do as much as they could as quickly as they could — trying to find therapeutics for people already infected, trying to figure out applications for drugs already approved for other purposes by the FDA. This sounded familiar. The reporter, echoing the voices I’d heard on the TV in my room, called the process sluggish. This also sounded familiar.

The exchange sounded familiar because the images and words being used to serve up the story of this Ebola outbreak were strikingly similar to the ones that had been used in the early years of the AIDS epidemic. With Ebola, the pitch had been increasing since two American medical missionaries had arrived stateside for treatment. Now, with the first transmission in the U.S., the response was deafening.

As with AIDS, the information was confused. On Oct. 9, Centers for Disease Control director Tom Friedan laid a little of what he later called “the messaging” on the public: “I’ve been working in public health for 30 years. The only thing like this has been AIDS. And we have to work now so that this is not the world’s next AIDS.” Already like AIDS? Or in danger of becoming the next AIDS?

* * *

In April 1982, National Cancer Institute acting director Dr. Bruce Chabner spoke to the House Subcommittee on Health and the Environment about “Kaposi’s sarcoma/opportunistic infections/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.” This was almost a year after the CDC first reported the appearance in the United States of a “new syndrome” that was also being referred to as the “4H disease" (it seemed to target heroin users, hemophiliacs, Haitians and homosexuals) and "GRID" (gay-related immunodeficiency); it was three months before the CDC settled on the name AIDS. Can you see the confusion? “While the illness seems to be concentrated among homosexual men, bisexual and heterosexual men, as well as women, are involved as well. Therefore,” Chabner said, the new syndrome was “of concern to all Americans.”

But while most Americans were probably concerned in some way with AIDS, only a select group of Americans were stigmatized: gay men. During the height of the AIDS epidemic, we saw images of young men, skin pale and stretched taught on their bones, sometimes spotted by the large maroon lesions of Kaposi sarcoma. We saw men being treated by doctors in full protective gowns, wearing masks, wearing goggles. We heard an apparent distinction being drawn between different groups of people carrying the same viral disease: hemophiliacs versus homosexuals and prostitutes. And then we learned about the ways their infected bodies were treated -- how schools barred children who were HIV-positive from attending classes, how bodies were placed in garbage bags, how funeral homes refused to accept them. Do you remember? I do. I started elementary school in the late 1980s, and fear of AIDS was everywhere. We even had a joke. Someone would ask a question, like, "Are you going to eat your fruit roll-up?" Answer: Yes. "Are you positive?" Yes.

And the final response: "Eeeeww! HIV positive?!"

This was curious, for we knew the facts on AIDS about as certainly as we knew our own birthdays. That would explain the precision of the joke: While the media referred to “the AIDS virus,” we’d been taught that HIV was the virus that led to the development of AIDS. We knew that AIDS was a disease transmitted through some — but not all — bodily fluids. Someday our lives would depend upon practicing safe sex, but for now we had to be careful not to touch anyone else’s bloody nose or skinned knee. Sure we had questions about specifics (what if you get in the pool and someone with AIDS and a bloody nose is in there too?), but our teachers answered such questions with science. As long as we were vigilant, we would be safe.

And yet something different was apparently going on with the adults: In the mid-to-late 1980s, a series of nationwide Los Angeles Times polls of people 18 and older found that about 50 percent of those surveyed supported quarantines for people with AIDS. Between 1985 and 1987, the number of people who favored “a tattoo for the people who test positive for the AIDS virus” nearly doubled — from 15 to 29 percent. When the Times conducted a poll again in 1989, it found that while the number of people who favored the suspension of “some civil liberties” for those testing positive remained at 42 percent, the number of people opposed to the suspension of civil liberties dropped by 12 points. And even as the number of newly diagnosed AIDS cases rose sharply, Americans said they felt less concerned about AIDS as a problem for their own personal health. In other words, as more people became sick, a significant proportion of healthy people felt safer — yet simultaneously less opposed to the suspension of others’ civil liberties.

I see here a divergence of feeling from fact, and a dubious sense of security reliant on a troubling amount of us-versus-them positioning. The latter requires a suspect population. In the case of AIDS, gay men were forced to occupy this role. At first, they were just sick and dying, but then they got loud -- screaming in the streets and blaming politicians for not acting fast enough to save their lives. Why wouldn’t they shut up? They had chosen to engage in risky behavior (note the language: always the choice, always the engagement, always the risk; a way of saying "gay sex," which most people would not actually say), which had led to an outbreak that was putting everyone in danger. So went the thinking.

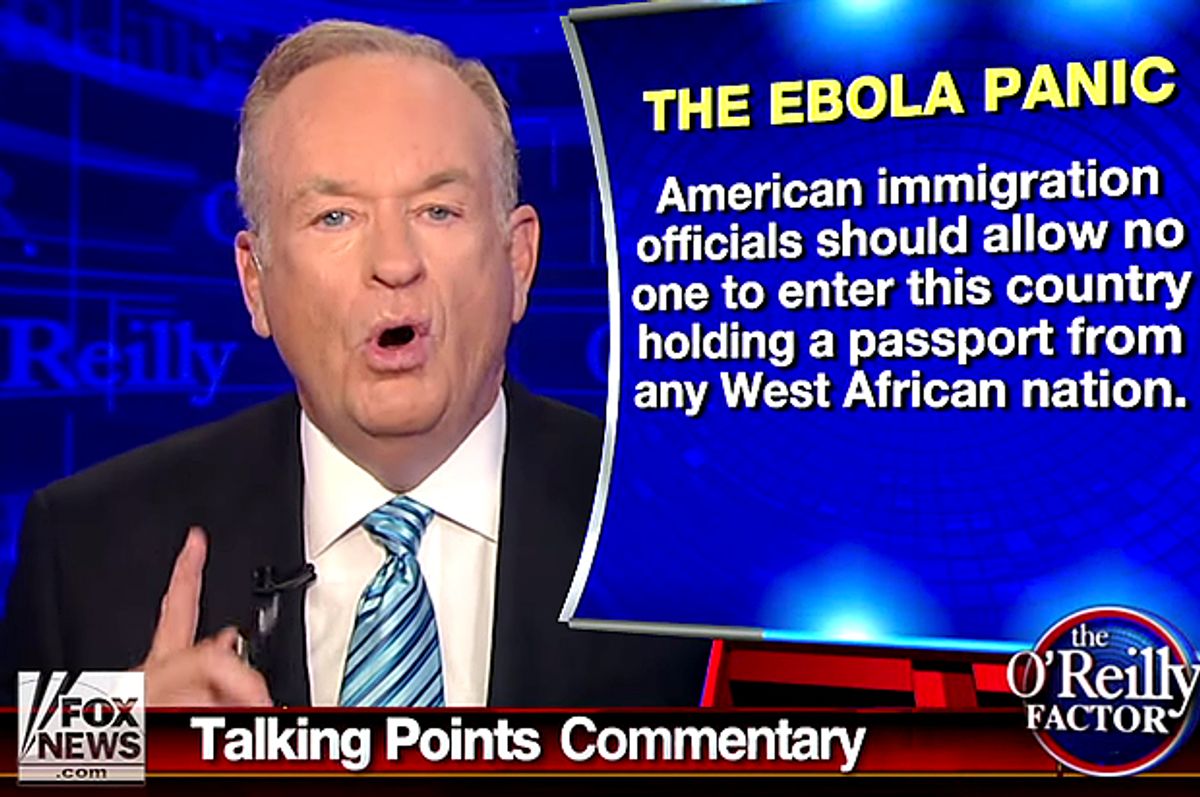

We’re seeing something very similar right now with Ebola. It’s a virus that came to us from Africa, a continent many Americans stereotype as backward, a place where sanitation is poor and water is unclean, whose dark-skinned inhabitants starve and have wars and do uncivilized things to each other as part of their culture. Why would anyone want to go there? People who choose to travel to the United States from Africa form suspect population No. 1. Thomas Eric Duncan, the Liberia man who brought Ebola to the United States, is a member of this population. He’s also unique: Of the nine people in the United States who have been treated for Ebola, he’s the only one who has died.

Healthcare workers who return or travel to the United States are also part of this suspect population. People in this category are stereotyped as medical cowboys, vacationing doctors and nurses who want to get in on “the action.” They’re hippies, progressives, radicals. They think they’re invincible. They write letters of protest; and one, Kaci Hickox, has been more audacious than the rest, showcasing her disdain for authorities by breaking the rules of her quarantine, doing interviews, riding her bike in public, suing the state of Maine.

Like people with AIDS, people in these two populations have chosen to engage in risky behavior (choice, engagement, risk: a way of saying "Africa," which cannot be said), actions that have put the rest of us at risk.

The fact is that you can only get Ebola from direct contact with the bodily fluids of someone who has detectable symptoms of the virus. As someone becomes sicker, the amount of virus in their bodily fluids grows, making them more contagious — and less mobile. Someone who has just developed a fever will have low amounts of virus, while someone who is experiencing explosive diarrhea and projectile vomiting will have higher level of virus. It’s worth pointing out that Thomas Eric Duncan only infected other people after he developed the latter set of symptoms; none of the people he was staying in a Dallas apartment with ever got sick. In this way, Ebola is not like AIDS: You can’t contract it from someone who appears perfectly healthy.

And yet that seems to be exactly what some people are afraid of. The feeling that something monstrous and invisible is lurking inside of ... who, exactly? New Jersey’s quarantine policy focuses exclusively on people returning from the three West African countries affected by Ebola, and the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals “requested” that attendees of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Health conference (held last month in New Orleans) who recently returned from Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea “remain in self-quarantine for the 21 days following their relevant travel history.”

What’s interesting about the Louisiana policy is that it creates a third suspect population: Anyone who has had any contact with an “EVD [Ebola virus disease]-infected individual.” On the surface, geography (by which I mean “Africa”) doesn’t matter here; all healthcare workers are unwelcome, no matter if they’ve just returned from caring for sick people in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea, or if they cared for Ebola patients at Bellevue Hospital, Emory University Hospital, the NIH Clinical Center, or Nebraska Medical Center. They’re all unwelcome because they all chose to engage in risky behavior.

“From a medical perspective, asymptomatic individuals are not at risk of exposing others,” the Oct. 28 Louisiana Department of Health letter says. “However, the State is committed to preventing any unnecessary exposure of Ebola to the general public.” In this scenario, Louisianans have the potential to fall through a hypothetical crack between medical perspective and reality, contracting a disease that is literally not yet contractable. This is how science becomes something you can choose to believe in (or not), and medicine something that is purportedly no longer interested in protecting the general public. Fall through this crack, and all healthcare workers are potential Typhoid Marys, secreting their symptoms away.

Back in the real world, I’m still thinking about CDC director Tom Friedan’s recent comments. When he talked about working to prevent Ebola from becoming the world’s next AIDS, what was his goal? Those of us who learned the facts about AIDS in school are all grown up. Some of us are parents, presumably the same parents trying to prevent principals and other people’s children from attending school after trips to Ebola-free African nations. The same people who, when polled, overwhelmingly support (nearly 82 percent, according to a Nov. 3 Reuters poll) quarantines for anyone returning from Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. The same public whose interest in Ebola, as measured by Google searches, remained low and flat until Thomas Eric Duncan was diagnosed on Sept. 30. It peaked again on Oct. 8, when he died and the U.S. government announced it would begin screening people for fevers at airports, and two more times after that: when it was reported that an Ebola-infected Dallas nurse who’d cared for Duncan had flown on a commercial flight just before becoming symptomatic, and when Dr. Craig Spencer tested positive in New York City. Today, interest in Ebola is almost at pre-U.S. “outbreak” lows.

“The drop in concern about AIDS,” a 1989 Los Angeles Times article said, “is due largely to lower concern among whites and people over age 40 that they personally will be affected by the epidemic.” Transmission rates peaked in 1992, 11 years and 254,147 cases after the virus’s discovery. Back then, it took massive educational efforts to help the general public shift its attitudes and behaviors, to think more about how to lower everyone’s chances of getting sick rather than focus on the actions of suspect populations. Since June, 15,351 people have contracted Ebola in West Africa. How long will it take for today’s adults to relearn an elementary school lesson?

Shares