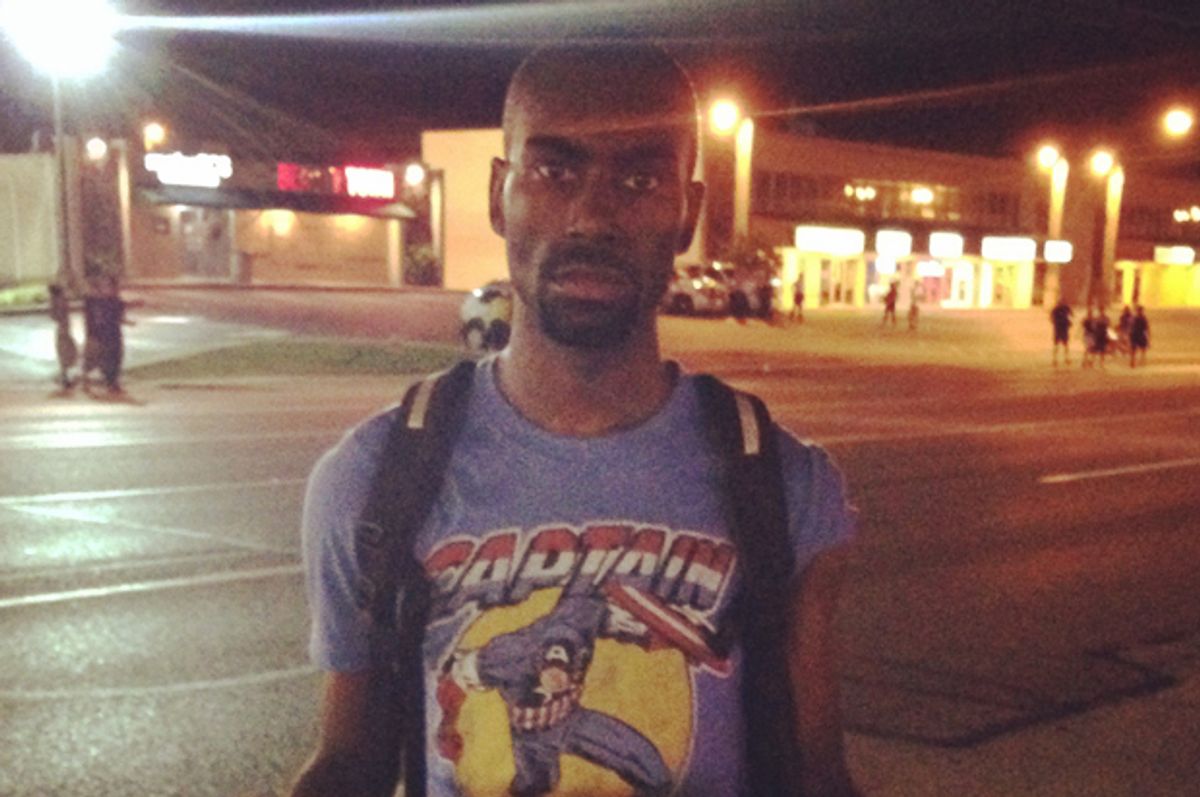

DeRay Mckesson had never met Michael Brown. He'd never even been to the St. Louis area before Aug. 16, but after watching the protests break across his social media feeds, he got in his car and headed out, leaving a note on his Facebook page asking if anyone could help him find a place to stay.

“I didn't know what was real or not,” he tells Salon. He had to see for himself, to be part of it. When he was tear-gassed for the first time, it only made him more committed to building a lasting movement.

That was almost four months ago. Since then, he's become one of the most recognizable social media presences keeping the public updated on the protests in Ferguson and elsewhere, as they've spread across the country. He started an email newsletter that he co-curates with Johnetta Elzie, another young activist based in St. Louis, sending out articles, action alerts, photos and tweets about the growing movement. The newsletter serves to connect people with actions and with each other, to filter an overwhelming volume of news reports, and to maintain a narrative of the movement going forward.

To Mckesson, the newsletter is about “fighting this fight in a different way.” He remembers the night the verdict came down that George Zimmerman, the Florida man who shot Trayvon Martin, would get off. “I remember it was like at night when the verdict came out and you were alone, you didn't know who to talk to, you couldn't find any information then, you didn't know what was real and what wasn't,” he says. “I didn't want that to be the story about Mike Brown.”

In the weeks following Brown's death, national media flocked to Ferguson, broadcasting from its streets and often unintentionally making itself the story, or focusing on conflict between protesters and police rather than on what was being built between the protesters on the ground and the people around the world who were following them on social media. Mckesson and Elzie's newsletter created a supplement to often-rushed social media accounts, and applied an activist's view to the news coming out of Ferguson. The stories they choose come with their commentary, notes like “Though we find this to be subtle victim-blaming, we encourage you to read it,” from Nov. 20 on a local media story on Vonderrit Myers, another young black man shot by police in the days following Brown's death. Or “As you read, tune into the slant that subtly blames the protests for a spike in crime in STL,” from Dec. 4.

“We try to make sure that there's a broad cross-section,” Mckesson says. “There are a lot of articles that get a lot of play that actually don't say a whole lot, whereas there are some articles that don't get any play but they're really powerful, and we want to make sure that they get visibility. We also want there to be a record of the movement, so when people look back they can track the movement through the news and the commentary.”

At the beginning, he notes, people told him there would never be enough news for the newsletter to continue, and yet 64 issues later, he says, “We're making really tough decisions every day.” For example, the morning after the news broke that a grand jury would not indict the officer who killed Eric Garner in Staten Island, they had to spend a lot of time winnowing down the many stories to those that included something different, something important, other than the news that presumably, most readers had heard.

The Ferguson protests broke on social media, and like the other social movements of the post-financial crisis era, social media has allowed people like Mckesson to reach an audience without relying on traditional news outlets. It has, the newsletter shows, also allowed them to become very astute critics of their own press coverage.

But the goal of the newsletter is not just to manage a public image; it is to motivate, as its title says, “Words to Action.” It opens with a countdown: number of days Darren Wilson has remained free. Number of days Kajieme Powell has been dead. Number of days Vonderrit Myers has been dead. It includes bolded calls to action, links to where readers can donate, tweet, submit and even buy T-shirts that support movement organizations. Notably, those organizations are local, small and mostly led by young people, part of this new generation of activists that, as Mychal Denzel Smith wrote, have shaken off nostalgia and have clear eyes set on making big changes, now.

“I think that what's really powerful about Ferguson is that it started because regular people without an organization came together because they knew something was wrong,” Mckesson says. “What is different about social media and I think what is true about this movement is that it allows many voices to be heard at the same time and it's not necessarily a competition for air, which is really powerful.”

Social media has, as well, Mckesson says, served to legitimize certain voices as authoritative — not by virtue of their position in a national organization, but because we can see through their eyes, night after night of violent police crackdowns, day after day of building. Social media can capture a moment — a die-in at a convenience store, a blocked highway — and give it life beyond its brief duration. It also adds pressure for the activists who have a large following to be there at every action. They wind up functioning, themselves, as journalists, albeit ones who are not being paid and supported by a major publication — and, Mckesson notes, ones who can say what they feel without having to adhere to some ideal of objectivity, without having to ask for the cops' side of the story.

That allows them to challenge the narratives that pop up again and again in the media. “People always ask about the anger and rage and, yes, we are angry, we are enraged, but that doesn't sustain a movement for 118 days. Love does,” Mckesson says. “There is this incredible sense of love in protest that is real that wasn't getting visibility. So I was tweeting, there's a cleanup crew, their job is to clean up after the protest. There is a woman who gets on the corner every day with her grill and feeds protesters as they walk to protests. There is somebody who passes out water every day, there is somebody who buys 50 pizzas, there are people who hold hands as they protest.”

The media's focus on rage, he points out, paints black people as monolithic, as only capable of one emotion, one type of expression. “One of the narratives of blackness in protest is 'the angry people outside,' as opposed to 'disenfranchised people who've been oppressed and victimized as they tried to grieve,'” he says. “We've been tear-gassed and shot at and LRAD'd and smoke-bombed and all these things and we still protest every day because we know that not only will our silence not save us, our surrender won't save us, a video camera won't save us. It is not that we are willing to die, it's that we are unwilling to live in an America where blackness equals death.”

As the protests have spread and continued around the country, blocking highways and streets, shuttering stores, dying-in in public spaces, Mckesson notes, “Ferguson manifests differently in many different places.” It is important, he says, to remember that when you are facing down violent police, it is hard to move beyond basic survival as a goal. People understandably have a hard time talking about systemic reform with a gun in their face or when they can't pay the bills. That's why, as an educator and activist, he feels compelled to stay in this movement. “You have to be alive to learn,” he says. All of the improvement in schools in the world will mean nothing if kids are being killed by the people who are supposed to protect them.

And so the struggle goes on. Mckesson spent the weekend in New York joining protests for Eric Garner, and he and Elzie plan to continue the newsletter — and their activism — as long as is necessary.

“Ferguson didn't show us that there's racial injustice in America. We knew that,” he says. “What Ferguson showed us was the power of people coming together to demand change. Ferguson made protests comfortable, gave people permission to protest. It allowed people to access their voice in a different way.”

Shares