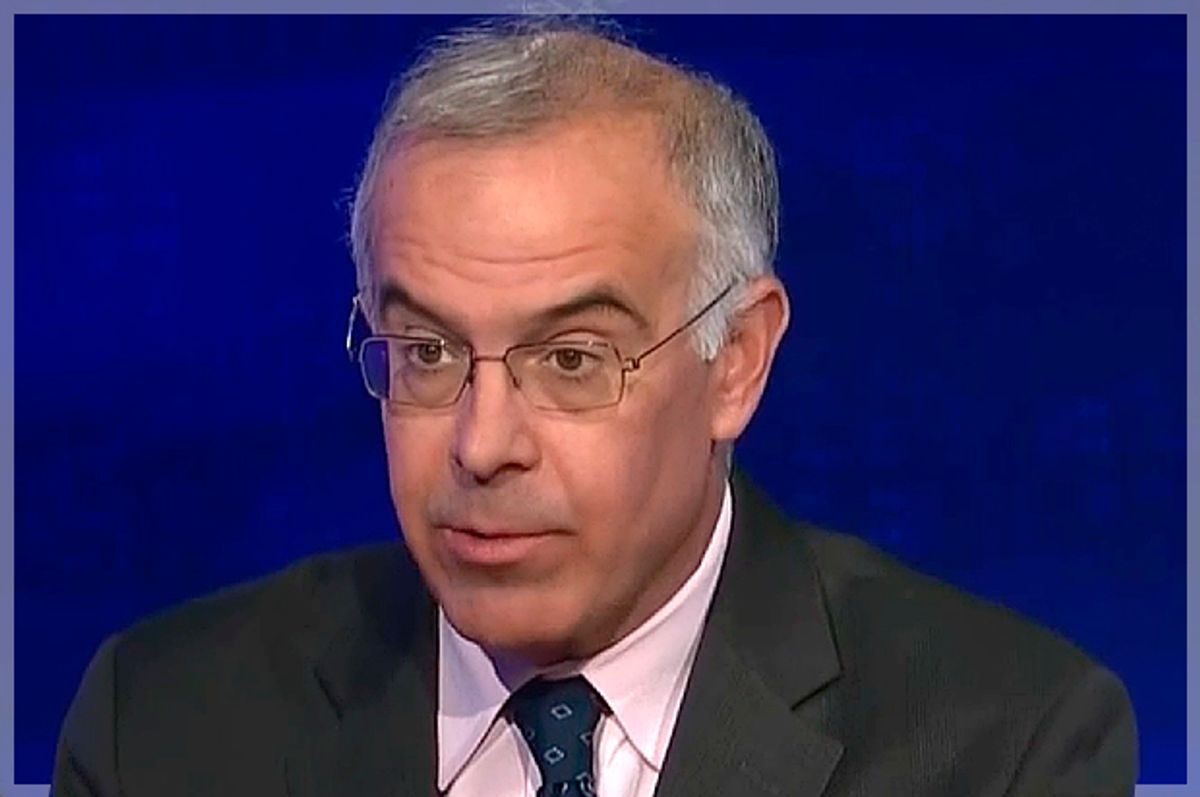

B.F. Skinner once told me that he hadn’t responded to Noam Chomsky’s attack on his book Verbal Behavior because he had seen it as a screed against a movement—Methodological Behaviorism—that Skinner did not feel a part of and had no interest in defending. I thought of that this morning as I read David Brooks’ paean to movements in The New York Times. “When you join a movement… ” he writes, “you join a community, which can sometimes feel like a family.” And a family you defend: “Believing becomes an activity. People in movements take stands, mobilize for common causes, hold conferences, fight and factionalize and build solidarity.” The outsider, though Brooks does not say it, becomes the enemy.

Perhaps were he a decade older (he was born in 1961), Brooks would have a less copacetic vision of movements—certainly of the one he identifies with. Where he sees a tradition, “a history of insight and belief,” in the movement surrounding the National Review that he joined as a youth, others of us, slightly older, remember the shadow-being of hate and repression of the era that spawned the magazine. To us, the magazine’s founder, William F. Buckley, was only the slightly less repugnant face of a movement characterized by memory of the disgraced Joe McCarthy. To us, as a result, all movements “irrespective of the doctrine they preach and the program they project, breed fanaticism, enthusiasm, fervent hope, hatred and intolerance; all of them are capable of releasing a powerful flow of activity in certain departments of life; all of them demand blind faith and singlehearted allegiance.” That, of course, is from the preface to Eric Hoffer’s classic The True Believer, one of the touchstones for American intellectuals of the post-World War II decades.

It’s odd that Brooks would pick today to laud movements, a day when Donald Trump is grappling with the legacy of the Ku Klux Klan, one of the most pernicious movements ever to flourish in the United States, and when its legacy may propel him to ‘Super Tuesday’ electoral success. Not only that, but ‘movement,’ today, also contains the specters of Mao and Mussolini. Little about either seems comforting.

The movements that Brooks mentions, however, including “paleoconservatives and neoconservatives… modernists and postmodernists; liberals, realists, and neoliberals; communitarians and liberation theologians; Jungians and Freudians; Straussians and deconstructionists; feminists and post-feminists; Marxists and democratic socialists… transcendentalists, existentialists, pragmatists, agrarians and Gnostics,” are mostly relatively benign. Even Marxism, as it has been practiced in the United States, is far removed from its Stalinist relatives in other parts of the world. His blinders against the realities of movements (for one thing, he never mentions cults, a logical extension of movements) make Brooks appear both idealistic and naïve.

Most of the movements Brooks lists aren’t so much movements as labels, anyway, the tags we put on blog posts making searching and identification easier. Brooks writes that a movement “depends on taking steps that are less in fashion today: committing to a collective, accepting a label, keeping faith, surrendering self to a tradition that stretches beyond you in time.” Even that is simply watered-down and prettied-up Hoffer. As such, it is still relevant only to the worst sort of movement—not to the nice soirees of Brooks’ imagination.

A real and effective movement doesn’t define itself the way Brooks sees the term, as a place to go to find community. A real and effective movement isn’t even a place, certainly not for belonging, but is a dynamic defined by a common goal. When my father would stand lonely vigil against the Vietnam War in 1966, sometimes joined by me and my brothers, my mother, and perhaps one or two more, he was not trying to build a community but to stop a travesty. The movement that grew over the next few years collapsed, not surprisingly, as the war wound down.

A movement, again, is defined by its action, not its embracing arms. If it lives beyond that action, it is likely to devolve into the type of regimentation of belief that Hoffer describes so vividly—which brings us back to Trump. Hoffer writes:

When the old order begins to fall apart, many of the vociferous men of words, who prayed so long for the day, are in a funk. The first glimpse of the face of anarchy frightens them out of their wits. They forget all they said about the “poor simple folk” and run for help to strong men of action—princes, generals, administrators, bankers, landowners—who know how to deal with the rabble and how to stem the tide of chaos.

This is what is happening to the conservative movement today. Trump portrays himself as the strong man of action.

And Brooks, one of Hoffer’s ‘men of words,’ is ‘in a funk.’

Shares