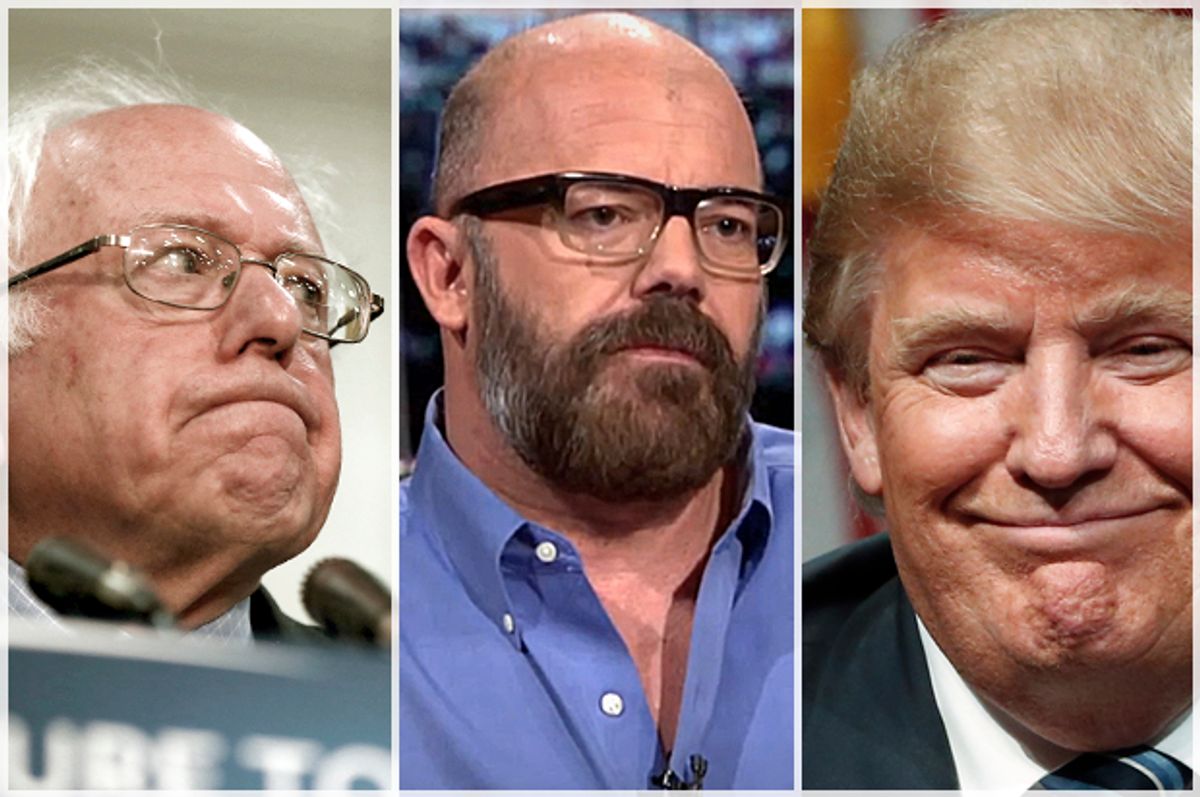

In Andrew Sullivan’s ballyhooed debut in New York magazine, he presents the candidacy of Donald Trump as a unique, “extinction-level” threat to the United States of America. One does not have to read far beyond his headline, however, to realize that Sullivan’s real purpose is to malign his usual antagonists on the left. His argument is an example of just how bankrupt the mode of liberalism he represents has become. It’s anti-democratic and culturally elitist message, however, reveals an opportunity for the left to reinvigorate its politics through an engagement with the humanities – an engagement that mainstream liberals like Sullivan have abandoned.

Sullivan establishes his cultural authority and diagnoses our contemporary crisis by opening his piece with a dubious reading of Plato’s Republic, painting a picture of Plato’s views on “late stage democracy:”

The very rich come under attack, as inequality becomes increasingly intolerable. Patriarchy is also dismantled…Animals are regarded as equal to humans; the rich mingle freely with the poor in the streets and try to blend in. The foreigner is equal to the citizen.

Sullivan evokes this portrait of radical equality not as a utopian ideal, but as an ominous warning. It is in a democracy that overthrows these implicitly natural hierarchies, Sullivan warns, that “the would-be tyrant would often seize his moment.”

Sullivan’s liberalism prevents him from directly endorsing Plato’s prescription for governance by “philosopher kings” as a means of preventing rule by tyrannous demagogues. Instead, he is forced to turn to the contradictory work of praising recent expansions in democracy even as he works to denigrate them. He imagines the “miraculous” election of Barack Obama as an expression of a potentially dangerously radical populism, but one in which America “lucked out” because Obama was “paradoxically, a very elite figure, a former state and U.S. senator, a product of Harvard Law School.” He praises the digital revolution that allowed voices like his own to speak truth to the power of corporate media, but laments the lack of elite control over the digital sphere has now created a space in which “the emotional component of politics becomes inflamed and reason retreats even further.”

Having issued these perfunctory and backhanded compliments to recent democratic developments, he turns his attention to the political movements on the left that our supposedly hyper-democratic moment has empowered, arguing that they both enable Trump and pose their own unique threats to rational public discourse. He warns that Black Lives Matter has “stoked the fires” of rage against the beleaguered white working class. He admonishes what he remarkably calls “the gay left” for lacking in “magnanimity” (emphasis in original) toward its homophobic antagonists. He excoriates the supporters of Bernie Sanders, “the demagogue of the left,” as “playing into Trump’s hands” for daring to ask questions about the ideological implications of Clinton’s connections to the political and business elite.

As an alternative to these dangerous leftist alternatives, Sullivan urges support for Hillary Clinton, for whom he has a few suggestions. Clinton, he believes, needs to “moderate the kind of identity politics that unwittingly empowers [Trump]” and “make an unapologetic case that experience and moderation are not vices.” (One wonders how Clinton might do more in terms of touting her own moderation and experience.)

Moreover, he argues the left should have supported those elite Republicans working to disenfranchise Republican voters by using party rules to prevent Trump’s nomination in the event that he were to garner a plurality rather than a majority of delegates. The war between left and right, Democrat and Republican, is in his view far less important than the war between the educated, reasoned, and disinterested elite and the impassioned, ignorant, and self-interested masses.

The crisis of demagoguery of which Sullivan warns, and the contradictory solution to this crisis that he poses – elites using anti-democratic measures to save democracy from itself – is not unique to our moment or even our century. Crises and backlashes such as these have been endemic to modern liberalism since its inception.

One hundred and fifty years ago, a notable one of these crises occurred when a demonstration of British workers rallying in support of the 1866 Reform Bill devolved into a riot when the demonstrators stormed the railings of Hyde Park after being denied entry by police. Witnessing this event inspired in poet and educational reformer Matthew Arnold a visceral revulsion that Andrew Sullivan would find familiar. Arnold’s disgust at the actions of this “mob” was in large part what inspired him to write Culture and Anarchy.

This famous essay argues that mass humanities education could cultivate in the anarchic working classes the rationality and disinterestedness they supposedly lacked. As scholars David Lloyd and Paul Thomas argue in Culture and the State, Arnold imagines that this feat could be achieved through the study of cultural “touchstones” of Western art and literature. In learning to see themselves represented in high culture, Arnold believed, the working classes would learn to be represented in politics: as Arnold famously put it, “culture suggests the idea of the state.” The vision of the role of humanities education in a liberal society presented in Culture and Anarchy dominated discussions of the social value of humanities education in Britain and the United States for nearly a century.

In a way it is surprising that Sullivan’s essay, with its high falutin' classical references and its championing of Arnoldian political values, never mentions the decline of humanities education in its litany of complaints about our contemporary political moment. Sullivan has written on the subject in the past, and the rise of Trump has been concurrent with a depressing set of milestones relating to education in the humanities, ranging from record declines in new humanities majors to shocking new lows in the adjunctification of humanities faculty. The humanities and the arts continue to be the first victims of the continuing assault on public education by conservatives and neoliberal reformers alike at the K-12 level.

Why then, in the midst of this “extinction-level event,” occasioned by Trump’s rise, are mainstream liberals like Sullivan not decrying the decline of the humanities as one of its primary causes? Probably because many liberals see contemporary humanities education as productive of the very sort of “identity politics” that they, with increasing boldness, disparage as a mode of politics equivalent to Trumpism.

Roderick Ferguson addresses this shift in liberalism’s relation to the humanities in his 2012 The Reorder of Things: The University and its Pedagogies of Difference. Ferguson brilliantly argues that, in response to the pressures brought to bear by feminist and anti-racist social movements on the university in the 1960s and 70s, universities did not affect a radical revision of humanities curriculum in the traditional disciplines, but instead created the interdisciplinary departments – ethnic studies, women’s studies, etc. – that were intended to contain the representation of these insurgent cultural traditions within the formal structure of the university without fundamentally challenging the ascendancy of the Western canon, and the cultural and political ideals, that Arnold and his acolytes championed.

Despite this attempted institutional cooption, the politicized scholarship that originated in the “interdisciplines” (as Ferguson dubs them) has thrived throughout humanities disciplines while the Arnoldian model has steadily declined. Theorists and activists emerging from within the academy have energized transformative social movements such as Black Lives Matter and thos associated with queer liberation. Instead of being celebrated, these emancipatory developments have been concurrent with an abandonment of the humanities by many liberal elites at the very moment they are under most strident attack.

The chauvinisms that cause many liberal elites to recoil at the thought of Black or queer studies being taught as a required part of a humanities curriculum are indicative of a broader political resistance to racialized and queer people being included in their political communities. This resistance is abundantly clear in Sullivan’s willingness to dismiss Black Lives Matter – a movement premised on the eminently reasonable assertion of the right not to be summarily shot by law enforcement officers – as an overly impassioned threat to the fragility of the white working class.

Sullivan shares with Arnold a distaste for racialized groups forcefully asserting their rights (ironically, Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy is at its most emphatic in declaring the Irish unfit for the political rights enjoyed by the English), but also for the white working class they both claim to represent. In his litany of evil portents leading up to the ascension of Trump, Sullivan cites a story about Sarah Palin, years before her entry into politics and working as “a commercial fisherman” being interviewed at a promotional appearance by Ivana Trump for her perfume line at a J.C. Penney’s in Anchorage. “We want to see Ivana,” the Anchorage Daily News quotes Palin as saying, “because we are so desperate in Alaska for any semblance of glamour and culture.”

What initially appears to be a snarky aside, in fact contains the essence of Sullivan’s argument. He does not fear Trump’s working class white supporters because they are racist. He fears them because he finds them uncultured, untrained in the mode of disinterested spectatorship that would teach them that both Ivana Trump’s perfume and radical politics are tacky.

Unlike Arnold, however, Sullivan has nothing to offer in the place of the “semblance of…culture” with which Trump has ostensibly lured his white working class supporters.

Having abandoned humanities education as a means of cultivating in the working class a willingness to be represented by liberal elites, Sullivan and those like him are left advocating a position that reveals their true allegiances. They would rather cheer Ted Cruz’s attempt to overturn the will of his party’s voters than support “the demagogue of the left” and his promise of free college education for all; they would rather castigate “political correctness” than question how their own neoliberal economic policies have alienated working class voters of all races; they would rather seize the state for the elite than see it defiled by the will of the voters.

One hopes that Clinton will not follow Sullivan’s advice to abandon “identity politics” or double down on an attempt to sell the value of elite leadership to the white working class. It seems unlikely, in any case, that she will make any further major concessions to a working class economic agenda. If she wins – and one must credit Sullivan for publicizing the fact that Clinton’s election is far from a foregone conclusion – it will more than likely be thanks to white liberal elites and upwardly mobile people of color, a coalition that will remain vulnerable to some form of Trump’s quasi-populism.

For the left to establish a multiracial working class coalition that can effectively combat the noxious politics that Trump has harnessed, it will have to embrace a pedagogical project, but an appeal to Plato on behalf of the Democratic Party’s would-be philosopher kings won’t cut it. Sullivan’s intuition that the Trump phenomenon is a crisis of culture as well as politics was essentially correct. His failure lies in his proposed response, which so clearly demonstrates the collapse of the Arnoldian marriage between liberalism and the humanities. This collapse signals a crisis but also an opportunity.

As the democratic socialist coalition that has coalesced around the Bernie Sanders campaign starts to look to the long game, it should pay heed to the innovative forms of cultural engagement being explored by interdisciplinary humanities scholars and students (often working against the institutional constraints imposed upon them) as a means of advancing its emancipatory project.

The rise of Trump through the ranks of a party working overtime to disenfranchise voters is not a crisis brought on by an excess of democracy, but by a lack of it. The radical work of American, ethnic, Indigenous, queer, and women’s studies scholars to champion education in modes of culture that empower rather than deracinate the marginalized citizens of our democracy is needed now more than ever. An embrace of this work offers the political left an alternative to the specter of fascism presented by Trump and the increasingly antidemocratic bent of mainstream American liberalism.

Shares