In his most recent weekly address, President Trump praised NASA’s “mission of exploration and discovery” and its ability to allow mankind to “look to the heavens with wonder and curiosity.” But left out of his statements was the work NASA does to peer back at our home planet and unravel its many remaining mysteries — a mission targeted for cuts in his administration’s budget outline released earlier this month.

In a budget otherwise scant on specifics, four climate-related NASA satellite missions were proposed for termination, including one already in orbit.

Those missions are aimed not only at helping scientists learn more about key parts of the climate system and how global warming is changing them, but also at practical matters such as monitoring the health of the nation’s coastal waters and providing earlier warnings of drought stress in crops.

The proposed cancellations mesh with statements made by Trump, administration officials and some members of Congress who have argued that NASA should be focused on outer space and leave the job of observing Earth to other agencies. But NASA’s unparalleled experience and expertise in developing new observational technologies and launching satellites makes it a crucial part of the Earth science enterprise, many experts say.

“I don’t see anybody else who could fill that gap,” Adam Sobel, a Columbia University climate scientist, said.

While the budget outline is not the final say, as Congress ultimately controls the purse strings, the proposed cuts are indicative of an “undeclared war on climate,” as David Titley, director of the Center for Solutions to Weather and Climate Risk at Penn State and a retired rear admiral in the Navy, put it. Eliminating the proposed missions and other climate science funding to save even a few hundred million dollars is short-sighted, given the long tails of climate change’s expected impacts in the U.S. and around the world, several scientists said.

“I think that those are very, very short-term gains that ignore a coming threat” that will endanger American lives and the economy “and not in 20 years, but now,” Kim Cobb, a coral expert at Georgia Tech, said.

“It is shortsighted and not what made our nation great,” Gabe Vecchi, a climate scientist at Princeton University, said. “It is only through targeted research and sustained monitoring that we can expect to be leaders in weather and climate prediction and understanding.”

The missions

While NASA’s overall budget of about $19 billion was cut by less than 1 percent, Earth sciences research was targeted for a larger share of the proposed cuts, losing about 5 percent of its roughly $2 billion budget. The proposed budget, the outline says, “focuses the Nation’s efforts on deep-space exploration rather than Earth-centric research.”

The cuts weren’t as deep as some climate scientists and advocates had feared, but many were surprised that particular missions were singled out.

“I did not expect that the president would specifically point at missions that he would like to be eliminated,” Emmanuel Boss, the science team lead of the Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud and ocean Ecosystem (PACE) mission, said.

PACE and the other three missions singled out — the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-3, the Climate Absolute Radiance and Refractivity Observatory (CLARREO), and the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) — cover different aspects of the climate system and are in differing stages of planning and readiness. But all are missions that scientists have been trying to get off the ground for many years, to plug gaps in our understanding of Earth’s complex climate and how it is changing.

PACE

The idea for PACE, which aims to monitor the microscopic phytoplankton that underpin the ocean food chain with finer detail than any previous satellite, has been kicking around for 16 years, Boss said, and would reverse a trend toward less high-resolution ocean observations in recent years.

Measurements of plankton and other aspects of the ocean would give scientists a better idea of how climate change is impacting the oceans, as well as how the oceans mediate the Earth’s climate. They would also help monitor the health of economically important fisheries and harmful algal blooms, which release toxic substances that can kill marine life and sicken humans.

“The primary mission is really to increase our knowledge of the oceans and what’s in there,” Boss said.

But the mission will also monitor clouds and aerosols — the dust and other tiny particles that float around the atmosphere — two of the major sources of uncertainty in current climate change projections.

The dual nature of the mission would also allow scientists a novel way to explore how the oceans and atmosphere interact, including how they exchange carbon dioxide (as the oceans are the main absorber of excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere).

“There’s never been, never, never been” a mission like this, Boss said.

Because PACE is still in the planning stages, mission costs are somewhat up in the air. President Obama’s budget request for the 2017 fiscal year allocated about $89 million to the satellite’s development for 2017, while $50 million was allocated in 2015 and $75 million in 2016.

Until NASA’s budget for 2018 is ultimately set by Congress, the mission remains on the development path set out by the agency, with development of the spacecraft scheduled to begin later this year.

OCO-3

The OCO-3 mission isn’t technically a satellite mission, though it’s a follow-on from one, the OCO-2, which launched in 2014 to get a clearer picture of when and where carbon dioxide is emitted into or sucked out of the atmosphere.

OCO-2, though, is somewhat limited, since it only passes over the same spot on Earth once every 32 days and at the same time of day and cannot be pointed at a specific spot of interest.

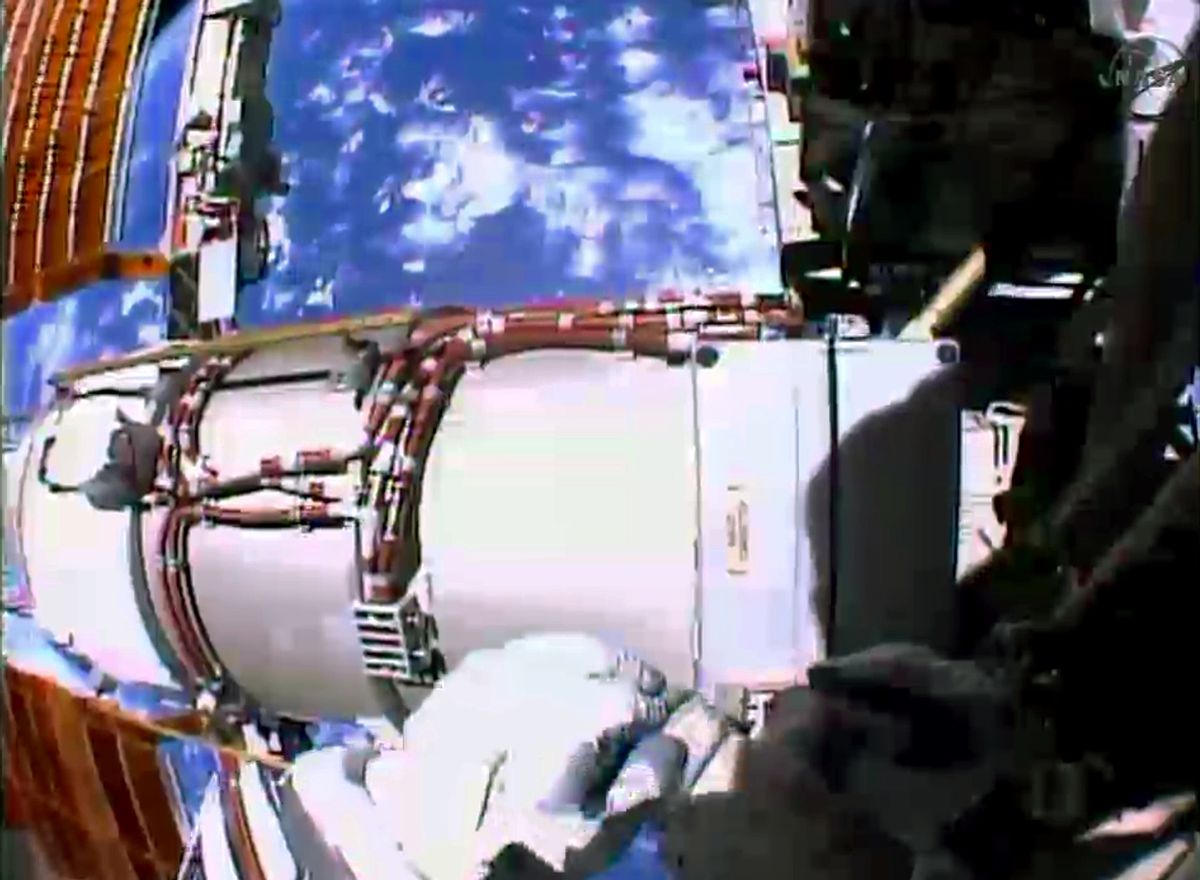

OCO-3 would address both of these limitations: The idea is to use spare parts from OCO-2 and mount them on the International Space Station, which would allow the instrument to be pointed at any spot on Earth to, for example, measure emissions from different cities or detect signs of drought stress in crops before such signs become visible to the naked eye. The orbit of the ISS also precesses, meaning it passes over the same spot at different times of the day, allowing the instrument to see how carbon fluxes change with the time of day.

“It’s operational flexibility is so much larger,” Paul Wennberg, an atmospheric chemist at Caltech and a member of the OCO-2 science team, said.

The loss of OCO-3 would be a “huge deal,” Cobb, who gasped when told it was slated for termination, said. The question of “where the carbon is going” is one of the most important ones right now in climate science, she said.

Because the parts for OCO-3 already exist, the mission is essentially ready to go after some routine testing. It would likely be launched on a commercial rocket already making a resupply trip to the station. These factors make it a relatively cheap mission, with a total cost target of about $115 million to build, launch and operate the instrument for three years.

CLARREO

The CLARREO mission, another one climate scientists have been pushing for years, is aimed at improving yet another source of uncertainty in climate science, one that comes from Earth-observing instruments themselves. The calibration of instruments varies from satellite to satellite and measurements on the same satellite can be impacted by factors like changes in the amount of sunlight hitting it. These variations can make it difficult to separate the sometimes small signals of climate change from the background noise.

“It leads to more uncertainties in these kinds of records on exactly how much is changing” and how much of that change is due to natural variations, human-caused warming or might be introduced by the satellites themselves, Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said. “That’s the classic climate problem.”

The idea of CLARREO is to measure thousands of wavelengths of radiation with more accuracy and to use it to calibrate all the other Earth-observing satellites, both for climate observations, as well as for weather.

“It is difficult and calibration is not a sexy subject,” Tim Hewison, a representative of the Global Space-based Inter-Calibration System, said, “but it’s behind everything we do as scientists.”

The Pathfinder mission targeted in the budget outline is a proof-of-concept effort that would put instruments on the ISS. The 2017 fiscal year budget request allocated $19.3 million for the development of the Pathfinder mission. It is unclear from the Trump administration’s budget outline whether the ultimate goal of launching a CLARREO satellite will also be impacted.

Even losing the Pathfinder mission, though, “would be pretty disastrous,” Hewison said.

Such a mission would more than pay for itself, as it could reduce the uncertainty of Earth’s climate sensitivity, or how much the planet’s temperature will rise given a certain rise in greenhouse gas levels. Answering that question earlier would mean society could save money whether temperature rise turns out to be higher or lower.

In the former case, society could save money by reducing emissions earlier and avoiding costly impacts if Earth’s temperature rises by a higher amount, while in the latter case, it could save money by avoiding having to spend money on emissions reductions.

“The value for the global economy far, far exceeds [the] costs” of a mission like CLARREO, Roger Cooke, a risk mathematician at Resources for the Future, a nonpartisan environmental think tank, said.

DSCOVR

DSCOVR is a slightly different situation, as the satellite is already in orbit and returning data to Earth. While its primary mission is focused on improving forecasts of space weather (such as solar flares), it also has Earth-facing instruments, including the EPIC imager, which constantly views the sunlit side of the planet. It is the Earth-focused side of DSCOVR’s mission that would be cut. The imager can help scientists better understand the planet’s energy balance, as well as measure ozone, aerosols and ultraviolet radiation at Earth’s surface, according to NASA.

Trenberth said it was unclear just how much those instruments will contribute to our understanding of Earth’s climate, “but the images that you get from that are spectacular.”

The only costs associated with the mission now for NASA are in retrieving and processing the data from the instruments it is in charge of, which, according to Obama’s budget request for the 2017 fiscal year would run less than $2 million per year.

Cutting off funding now would be “letting the stream [of data] go to waste” Trenberth said. “That just seems foolhardy.”

NASA’s climate role

Climate scientists broadly consider NASA’s role in building and maintaining missions like these as a critical part of pushing climate science forward and a role that NASA is uniquely poised to fill. Its wealth of engineering expertise would be virtually impossible to replicate in another agency.

The unique dual nature and advanced capabilities of the PACE mission, for example, have required the expertise of NASA’s engineers to get off the ground.

“It’s very much one of NASA’s kind of missions where it’s developing new technology,” Trenberth said.

Instead of cutting some of these missions, Titley thinks the Trump administration would be better served by trying to iron out the transition from NASA’s development of experimental Earth-observing missions to their longer-term, everyday use by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a longstanding hiccup in the satellite missions pipeline.

“My question sort of from a government bureaucrat perspective is how do we sustain” that process, Titley, who is also a former NOAA chief operating officer, said. While the PACE mission, for example, would bring much-needed upgrades to ocean observations, it is only slated to operate for five years. The question is how to keep the momentum going and develop those observational capabilities beyond that timeframe, he said.

“That requires adults to sit down and prioritize these missions and figure out what you’re going to do,” Titley said. If this administration has done that in their budget-cutting process, he hasn’t seen any evidence of it, he said. “They just seem to be random hackings that don’t support anybody’s strategy.”

Several scientists also pointed to the fact that because of NASA’s work, the U.S. had long led the world in Earth observation missions and innovation, something they say should fit in with the president’s “America First” strategy.

While the European Space Agency and China’s space agency have talked about supporting missions similar to CLARREO, neither is anywhere close to as far along as NASA is in the process. Similarly, the Germans have been working on a mission akin to PACE, but lag far behind the U.S. in the process, Boss, the PACE mission scientist, said.

“If America is to be first, this is the kind of mission that we do,” one that is unique and brings engineering challenges that move technology forward and help the U.S. attract the best and brightest scientists, he said.

“If you’re not leading that, the brains are not going to come here, they’re going to go elsewhere,” Boss said. “There’s a direct economic impact to not leading in science.”

And while missions can be resurrected when money becomes available again, as has happened before with both CLARREO and DSCOVR, that process isn’t as simple as taking the parts out of storage and picking up where you left off because of the human expertise invested in them.

The teams of engineers and scientists working on these missions have been building their expertise and are primed to work on these missions now. If the missions are cancelled, those people will move on to other projects and jobs, so restarting a mission would likely mean spending even more money to bring a new team up to speed, Boss said.

Losing these missions would also hamper the ability of the climate science community to continue refining their understanding of Earth’s climate and how it might change in the future.

“I can’t overstate the urgency to learn all that we can about climate change now,” Cobb said. Even a delay of four years, when a new administration could potentially restore funding, would be a setback and a loss of “precious time” for the aims of these missions.

“We needed them 20 years ago,” Cobb said.

Whether these missions will ultimately be scrapped, though, remains in the hands of Congress. Trump will release his full budget request later this spring, at which point budget committees in both houses of Congress will set overall spending caps and various appropriations committees will decide how to dole out the money allotted to them.

Many climate scientists, and the professional associations they belong to, are working to advocate for maintaining and even raising spending on science research, particularly by emphasizing the economic benefits that such research can provide. But many are also simply trying to push on with their work, watching and waiting to see what happens.

“Until Congress actually passes something . . . they just sort of muddle on,” Trenberth said.

For his part, Vecchi took some hope from other comments Trump made during his weekly address that touched on how much NASA can teach us and the “the need to view old questions with fresh eyes; to have the courage to look for answers in places we have never looked before; to think in new ways because we have new information.”

Vecchi thinks that NASA’s work in observing the Earth is a key part of that endeavor.

“The observations that NASA has made of the Earth and of space have opened our eyes to amazing wonders of how the planet and our universe function — observations that have led to new fundamental understanding and practical outcomes,” he said in an email. “It is mild to say that NASA has been a pioneer organization when it comes to understanding our planet, and I hope that its observations continue to shine a light on the deeper mysteries of atmosphere, ocean, land and ice.”

Shares