In 1995, the Los Angeles Times asked Krzysztof Kieslowski how movies should participate in culture, and this was his reply: "Film is often just business -- I understand that and it's not something I concern myself with. But if film aspires to be part of culture, it should do the things great literature, music and art do: elevate the spirit, help us understand ourselves and the world around us and give people the feeling they are not alone."

Now those are words to make movies by, and Kieslowski certainly did. Nearing the end of the millennium, when even the best works of those other European giants, Federico Fellini and Ingmar Bergman, had started to seem fossilized, Kieslowski, their contemporary, found his stride. The great Polish filmmaker, who was raised in an economically impotent, foreign-dominated runt country and came of creative age in a climate of political censorship, had finally accumulated the resources he so clearly deserved: a literate and deep-feeling world audience, complete artistic freedom and plenty of Western money to fund his work.

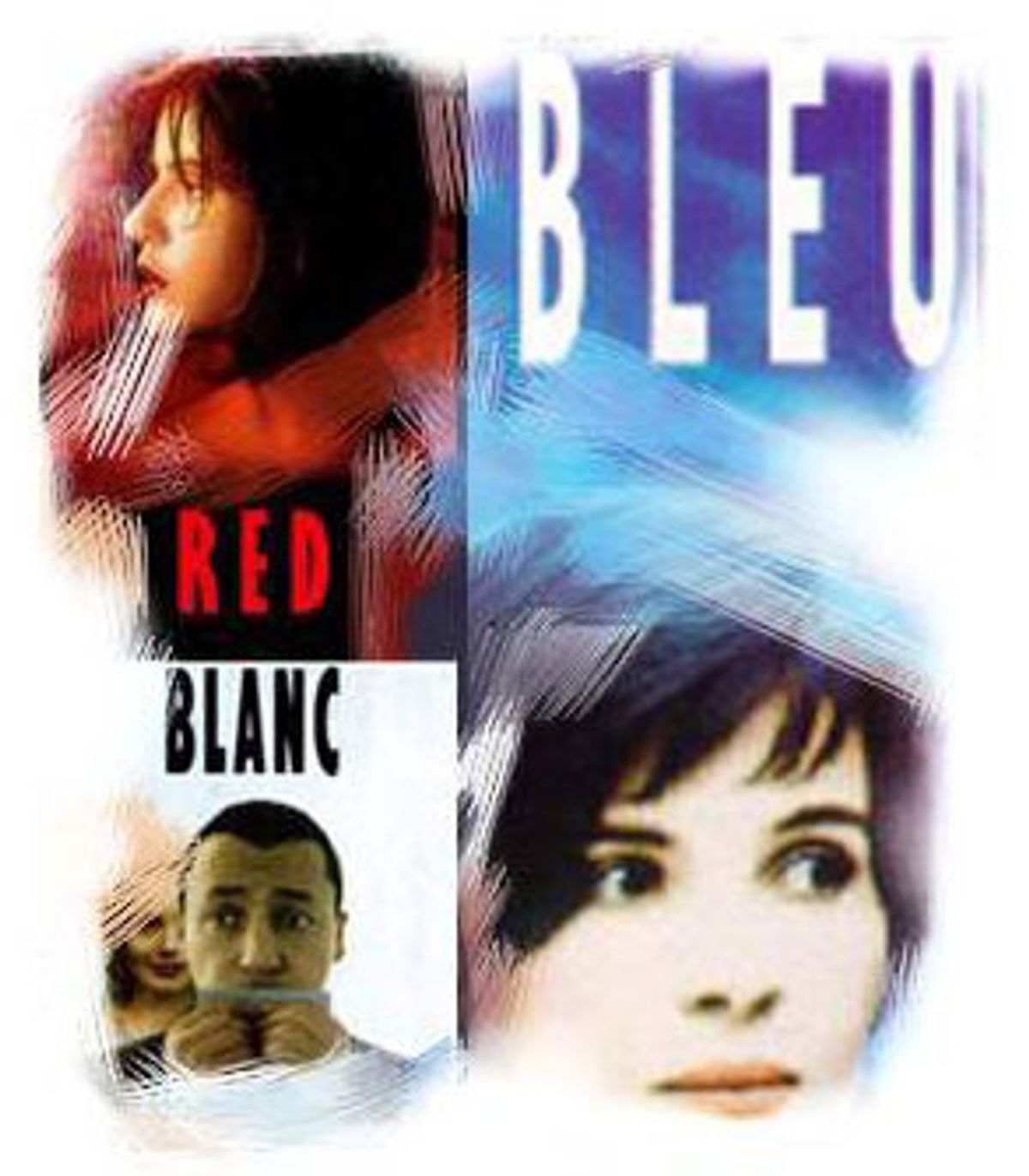

He invested wisely. Kieslowski's "Three Colors" trilogy was more than just the slickest concept album in the history of European cinema. It was a quantum leap for the medium, a reminder not only of what was possible, but what was necessary. As "Blue," "White" and "Red" hit theaters, one at a time, moviegoers everywhere began feeling giddy. They knew something very special, and vital, was afoot. For those who'd seen Kieslowski's "Decalogue" (a serialized tone poem on the Ten Commandments, and also an astonishing masterpiece), the prospect of another segmented, philosophical parable was all too tantalizing. For those who hadn't, "Three Colors" was like nothing they'd ever experienced. Film didn't seem like such a youngster among the arts anymore.

The richly textured trilogy capped Kieslowski's extraordinary career, taking on the deepest and most complex moral subjects with grace and panache, but always at ground level. Ostensibly it was derived from the French Revolution themes of liberty, equality and fraternity, and their corresponding colors in the French flag. But the films are deeply personal and in many ways Polish; they restore those lofty concepts, without diminishing them, to humble human proportions.

In temperament they differ significantly but are thematically unified by Kieslowski's inquisitive, haunted and wryly humane sensibility. His genius is evident not only in the fluency with such varied tones -- the inward, meditative drama of "Blue," the oblique social comedy of "White" and the nimble, all-knowing mystery-romance of "Red" -- but the elegant orchestration by which he unites them. Each involves an enormous narrative arc: The characters endure debilitating betrayals and literal or figurative deaths, then respond to the prospect of renewal so generously provided for them by the director. Yet each is lean and swift, clocking in at around an hour and a half. Not bad for so intense a sensual, emotional and spiritual workout.

In "Blue," Julie (Juliette Binoche) is rather brutally "liberated" by the death of her daughter and husband, a famous composer, in a car accident. To defeat grief, she discards her former life. "I don't want any belongings, any memories," she says. "No friends, no love. Those are all traps." But her husband's music, which, Kieslowski suggests, was really created by her in the first place, is irrepressible. As is true throughout the trilogy, Zbigniew Preisner's score, here a funereal concerto gradually realized through Julie's reclaimed inspiration, reinforces the tone and theme of the work from within. It's a functional part of the narrative. What's more, even in such a visually sumptuous work, Kieslowski is brave enough to tell us -- through blackouts, blurred focus and commanding stillness -- not to look, but simply to listen.

Binoche has done plenty of good work, but this remains her best, and I'm not just saying that because I think the Academy blew its chance, with "Blue," to start an award for best haircut. Julie is almost impossibly chic, partly for being viewed through the director's Eastern European eye, and partly, rightly, for the exquisite care with which Binoche measures her performance; she taps right into a cool, beguiling, divine feminine energy rarely seen on-screen, and slowly pours it into Julie's life.

"White," a playful riposte to the earnestness of "Blue," is a sort of ironic Polish Horatio Alger story, well stocked with lumpen misfits and great Slavic faces. Here, "equality" is a matter of comeuppance. Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowski) is an oafish and adorable Polish hairdresser whose porcelain-skinned Parisian wife (Julie Delpy) divorces him for failing to consummate their marriage. The mere fact of being in France renders Karol impotent. He loses everything, but meets a fellow Pole who agrees to smuggle him back to Warsaw. There, Karol shrewdly bullshits his way through his country's newly opened markets, amasses a dubious fortune, wills it to his wife, fakes his own death and frames her for his murder.

Kieslowski, who so keenly satirized the crippling excesses of communism in his earlier work, unflinchingly has a go at training-wheels capitalism, but not without affection for the thawing tundra of his beleaguered mother country. Having been stuffed in a suitcase, flown in cargo from France to Poland, stolen by bandits, robbed and beaten up, Karol finally looks out across the speckled white vista of a frozen landfill, and says, "Home at last!" Shortly thereafter Preisner's tongue-in-cheek tango begins, which will carry Karol through the dance of his revenge and into equality.

The fraternity in "Red" also begins ironically, through a tangled knot of missed or blocked connections. A young model, appropriately named Valentine (Irène Jacob), patiently endures the remote jealousy of a geographically and emotionally unavailable boyfriend, while coming close to crossing paths with another young man who lives right on her block. By chance -- or not -- Valentine runs over a German shepherd and must track down its owner, a retired judge (Jean-Louis Trintignant) who lives alone and eavesdrops on his neighbors' phone calls.

The judge has not recovered from a long-ago romantic betrayal, ostensibly because fate never allowed him to meet the right woman, namely Valentine. Their lives enlace, and we learn with the usual help from Preisner -- this time in a swirling bolero, which modulates into a minor key to raise the neck hairs just as certain scenes take on a supernatural charge -- that the young man on Valentine's block is precisely reprising the judge's early life.

Not arbitrarily (nothing in Kieslowski's work is arbitrary), "Red" takes place in Geneva, splitting the geographic and cultural difference between the first two films and honing the scope of the entire work only to broaden it, finally, beyond all borders. As succinctly described by Kieslowski's longtime co-writer, Krzysztof Piesiewicz, "Red" is "a film against indifference." It is Kieslowski's "Tempest"; the judge, a formidable magician and authorial stand-in, is his Prospero. Like Shakespeare's play, the film is aware of its own theater, and of its place as the summation of an oeuvre.

Undaunted by the tremendous emotional and moral valence he has by now invited us to expect, Kieslowski controls the film magnificently, putting to use the shapely formal precision he took an entire career to work out. After sustaining the increasing complexity and momentum of the whole trilogy by riffing and rhyming and ducking and dodging through it, he builds a celestial climax, beautifully braiding the three installments into a moving and deeply satisfying conclusion.

For this final magic act, Kieslowski unleashes his tempest on a ferry full of more than a thousand people, rescuing only a handful -- who happen to be the trilogy's main characters. By sparing his darlings, and bringing them safely together, he claims a small but potent victory for the director's prerogative, not to mention the last of the revolutionary concepts, fraternity.

Kieslowski never subscribed to the pompous idea of filmmaker as an engineer of human souls. He began as a documentarian but eventually found it disingenuous and gave it up, choosing only to intrude on lives that he'd invented (most often in collaboration with Piesiewicz). But the documentary work served him well. He became an illusionist with no illusions, a conjurer of relativity but not a relativist. For all his empathy, the truth about people could not help but make him an ironist.

What made Kieslowski a master, though, was that he remained capable of awe, and made a conscious effort to transcend pessimism, to manage the unmanageable proportions of life -- while bowing to its beauties and mysteries -- through his own creative process. "Three Colors" is a supreme example.

It's almost funny how everything in these films, even ugliness, is beautiful. That's not the gloss of French money, it's a declaration from the director. Watched in order of their release, the films progress through a literal warming, a triumphal emergence from isolation into community, from the numb, bloodless chill of "Blue" through the pale fire of "White" to the blushing, blossoming heat of "Red." And it happens largely without the detachment and abstraction of lens filters; instead, mostly, through objects within the environment: food wrappers, clothes, upholstery, vehicles, furniture, walls. What fun (or madness) it must have been to work in Kieslowski's art department! Like the chapters of the "Decalogue," the "Three Colors" films were photographed by various cinematographers but governed by a single vision.

In each case, the title color is vibrant and portent, variously associative: Blue can be water or ink or memory, white can be pigeon shit or a wedding dress or Warsaw ice and possibility, red can be blood or bubble gum or enchantment. The synthesis of the three, inevitably, is a perfectly balanced composition. As Matisse said, anybody can throw two colors together, but it takes a master to add the right third one.

Of course, the visual arrangement of the French flag was old news by the time Kieslowski came around. But the notion of colors as concepts was a deceptively simple way of making explicit the filmmaker's career-long crusade for a deeper perception of everything that remains beyond our perception.

This wasn't just art-house hogwash. Kieslowski invented a cinematic vocabulary for these films so he could speak more clearly to his audience. When he winks, it's a magician's wink, or a favorite uncle's -- or a favorite uncle who is a magician, not the dime-store kind but a quiet and sublime old wizard -- telling you: "Pay attention now, here comes something special, just for you." When he allows a perplexing gesture, it's to remind you to stay engaged, to wonder about the perplexing gestures that surround you, and to get some life out of them.

After "Three Colors," Kieslowski retired; he'd become impatient with every part of making movies that wasn't casting or editing (not surprising, given the doting just-rightness of his casts and cuts), and he was exhausted from the trilogy's merciless production schedule. He said he simply wanted to read and smoke in peace. It had a whiff of "OK, I can die now," and so he did, too soon thereafter, at the too-young age of 54. In some ways it seemed all right for him to go. He'd covered everything.

OK, maybe not. We still have our moral agonies and spiritual quandaries, our confounding and unknowable possibilities. And, although we might not have realized it until he showed us, we have the elastic and resilient heart to deal with them. In truth, Kieslowski hadn't really stopped working. He and Piesiewicz had a new trilogy in mind, about Hell, Purgatory and Heaven. The audacity! Again, the tantalizing promise! Were they serious? Kieslowski suggested that he was, reportedly telling Miramax head Harvey Weinstein that Hell clearly had to be set in Los Angeles.

After her fashion show in "Red," Valentine meets the judge in the now-empty theater; they're alone together, nestled gorgeously in a swath of plush-red seats, with the tempest just outside batting at the doors. Valentine says she feels like something important is happening around her and she's scared. The judge takes her hand and says, "Is that better?" It is. And it is to Kieslowski's credit that even with all the magic and maneuvering that has brought him, his characters and us to this point, nothing can match the power of this simple gesture. It will always be the pinnacle of a work of art that's out of this world, but so close to home.

Shares