Nick Nolte has become the movies' magnificent wreck, an image of battered masculinity that is far more beautiful than any preserved and mellowed good looks could ever be. There have been other stars who could be described that way, the older Humphrey Bogart for one. But where Bogart appeared graven, sepulchral, Nolte's face retains a fleeting trace of youth. There is a suggestion of unformed boyishness in his cheekbones, and expectancy in his narrow, hooded eyes. It's a face that, for all the hard knocks it looks to have undergone, seems unprotected, as if the crags and hollows were still tender to the touch instead of evidence of the emotional scar tissue he has formed. The tension in a Nolte performance has always been between his huge, lumbering body, the voice that sounds roasted to a husk, and the jackrabbit energy that expresses itself most often in some sudden, raspy exclamation.

Too knocked around to seem like undamaged goods, and too wily to seem down and out, Nolte shakes the potential sentimentality out of the traditional movie icon of emotionally bruised hero. If he's in touch with the sources of his pain he's also in touch with the things that bring him pleasure. It's even odds that will win out in any Nolte performance, and that balancing act is the perfect metaphor for the dazzling new movie in which he stars, Neil Jordan's "The Good Thief."

It was a gamble for Jordan to attempt a remake of a movie as esteemed as Jean-Pierre Melville's French classic "Bob le Flambeur," as much of a gamble as any that Nolte's character undertakes in the course of the movie. This long shot pays off -- in spades. Not only has Jordan made a movie that's looser, hipper, freer and -- abetted by his great cinematographer, Chris Menges -- more sheerly beautiful to look at, he's also made the best movie of his career.

Melville's suave elder statesman of the underworld here becomes Bob Montagnet (Nolte), the son of a French mother and American father, living in the South of France. A former thief who's taken to scouring the backrooms of seedy clubs for poker games, indulging his love of heroin when he's not at the tables ("Gambling and dope don't mix" is one of his maxims), Bob is on one long losing streak. He's down to his last 70,000 francs and when a bad day at the track takes care of that, he's game for the plan his associate Raoul (Gérard Darmon) has in mind.

Raoul's scheme is the Holy Grail of crooks: knocking over the casino at Monte Carlo. Except there's a twist. Instead of the money in the vault, Raoul proposes going for the priceless art masterpieces the casino's Japanese parent company has stashed in a secret underground vault. (The owners are so nervous about the paintings that they've decorated the casino itself with top-notch forgeries.)

One big haul and then we get out has been the setup for so many hard-boiled tragedies ("Rififi," "The Asphalt Jungle," "The Killing") that you think you see where "The Good Thief" is headed barely before it's begun. But nothing Jordan (who also wrote the script) does conforms to genre expectations, least of all his conception of his hero. Bob could so easily have been the beautiful loser, the man whose grace is revealed in loss. Except that on Nolte, whose specialty is a combination of gruff, bearish physicality and emotional vulnerability, grace never looks especially graceful -- or at least what we think of as graceful.

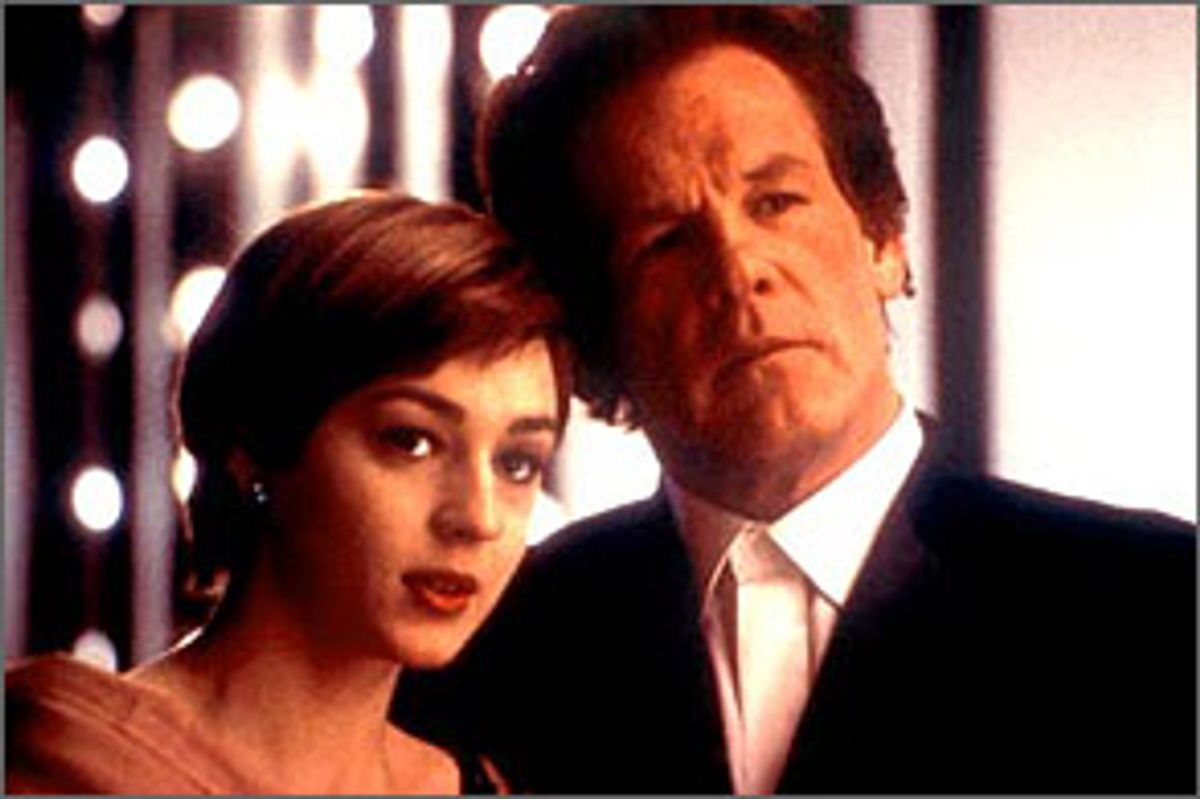

Bob is, to be sure, an enormously attractive, even romantic figure. Having a chat with Roger (the wonderful Tchéky Karyo), a cop who's much more his buddy than his nemesis, Bob looks momentarily at peace savoring his bleary-eyed heroin high. And when he takes in the young Russian hooker Anne (the stunning newcomer Nutsa Kukhianidze) to save her from the beatings she's receiving at the hands of her pimp, he's very much the crook with the heart of gold.

But, thankfully, the movie isn't about Bob's salvation. (Why do directors think salvation is such a good idea for movies anyway? Everything we like about raffish heroes is usually washed out of them when they're redeemed.) It's about how Nolte's particular brand of beauty shines as Bob gets to put his brains and talents to work, as he gets a chance to once more be the best crook he can be. Nolte has given great performances before -- in "Affliction," "Life Lessons," "The Prince of Tides," "Weeds" -- but with the possible exception of "Down and Out in Beverly Hills" he's never had the sheer fun he seems to be having here.

Bob may be on a losing streak but there's nothing of the fool about him and almost no desperation. "The Good Thief" isn't about a down-and-outer's last desperate stab at a big score. Bob is almost existentially resigned to the reversals of fortune that gambling and thieving (and taking dope) entail. The movie is about how he regains perfect harmony with a life of taking risks -- as the stakes get higher you can almost hear his insides thrumming like a tuning fork. As the risks mount, Bob becomes more confident, almost relaxed in his attention to every detail of the crime. Even his approach to kicking heroin is matter-of-fact (he handcuffs himself to the bed with a bucket and a tub of ice cream). You wouldn't think of Cary Grant or Fred Astaire watching Nolte's performance, though it has one big thing in common with that level of classy elegance: The sweat doesn't show. (Bob makes only one lapse in taste -- he insults French rock 'n' roll just after we've heard Johnny Hallyday's terrific version of "Black Is Black" -- called "Noir C'est Noir" -- which cuts the Los Bravos original.)

Jordan rewards Bob's cool, witty composure -- and us -- with a long sequence where Bob and Anne gussy themselves up (Nolte in a gorgeous Armani suit) and head for the casino. This part of the movie recalls the glamorous tension of the gambling scenes in Jacques Demy's "Bay of the Angels," and the lighter spirited scenes between Daniel Auteuil and Vanessa Paradis in "Girl on the Bridge." Watching Nolte and Kukhianidze at the roulette and blackjack tables, reacting with perfect élan to every spin of the wheel, every new card laid down, is like listening to a great jazz solo. You have no idea where the soloist is headed and yet his sheer confidence never makes you doubt he'll get there. It's a sustained sumptuous cliffhanger.

That devil-may-care spirit is entirely Neil Jordan's contribution. You won't find it in "Bob le Flambeur." Jean-Pierre Melville is a hard director to make up your mind about. I enjoy the gloomy fastidiousness of his gangster films like "Le Samourai" and especially "Le Cercle Rouge," which is currently making its way around the country in the only complete version that has played here, and which I'd take over Jules Dassin's "Rififi" any day. But if you've seen Melville's hothouse adaptation of Jean Cocteau's novel "Les Enfants Terribles" it's hard to resist a sneaky suspicion that in his dedication to genre films Melville was consciously working beneath his capabilities. He wasn't a born genre filmmaker, as the deliberation and self-seriousness of his crime dramas show. He wanted to invest them with more import than they could bear (import that doesn't feel like a stretch in a movie that's at home in the genre, like the great noir "Out of the Past").

"Bob le Flambeur," from 1956, is an obvious link between the professionalism of '50s French cinema and the more poetic approach the New Wave directors took to the crime genre, in François Truffaut's "Shoot the Piano Player" and Jean-Luc Godard's "Breathless." (In that film, Godard drops a reference to the hero of "Bob le Flambeur," and Melville himself appears as the author who says his greatest ambition is "to become immortal and then die.") "Bob le Flambeur" is a terrifically enjoyable movie even if its doomed romantic fatalism feels like an inevitable and predictable sop to the genre. The movie is the product of an intellectualized infatuation with Serie Noire paperbacks, '40s American noir, and the luxuriant self-pity of Edith Piaf songs.

Essentially, Melville was indulging himself in a form of weepy cabaret while, here, Neil Jordan is making jazz. There's a playful springiness to the movie that keeps any hard-boiled sogginess at bay. You hear it in some of the movie's lightning-fast exchanges. The actors aren't talking noticeably fast; they just live in a world where everyone functions at the same syncopated tempo. The wit of the dialogue sometimes catches you on the rebound.

The best movie Jordan made previous to this, "Mona Lisa," did not escape a certain noirish sentimentality. That didn't hurt the picture. You wanted it to be a gorgeous, sad song, like the Nat King Cole number it was named after. "The Good Thief" is, like "Mona Lisa," a noir reverie, but one that sees through the sop in which noir can revel. My gut tells me that, for all the darkness noir brought into standard Hollywood sunshine, it also brought another form of sentimentality in disguise. The best noir films escape conventional morality, but much of the genre often makes just as sure as conventional Hollywood movies ever did that bad people, no matter how much we liked them, get punished.

"The Good Thief" is cheerfully guilt-free about our fascination with thieves and our complicity in wanting to see them get away with it. The photography by Menges (himself the director of such films as "A World Apart," "Second Best" and "The Lost Son") is so warm and beautiful that it feels like we're being flattered just sitting in our seats drinking it in. Menges is such a master of lighting that even the scummiest dive-bar backroom has a palpable glow. Nolte's house, with its peeling walls, exudes an air of chic decay. And the beauty Menges gives the surroundings extends to the actors' faces, which feel both utterly individual and as iconic as anything in a Sergio Leone film.

You bask in the landscape of faces. First there is Gérard Darmon, whose long, pointed mug makes him look something like a chiseled French Fred Gwynne. Then there's Bosnian director Emir Kusturica, a hirsute, doughy presence who turns up as a security expert involved in the heist for the sheer pleasure of defeating his own security system. (Kusturica might be auditioning to succeed Robbie Coltrane as Hagrid in the "Harry Potter" series).

There's a lot of good acting throughout the movie. As Bob's young protégé Paulo, who falls in love with Anne, Saïd Taghmaoui (he was the Iraqi soldier who tortured Mark Wahlberg in "Three Kings") has a baby-faced softness. When his anger and jealousy threaten the entire heist, you feel as if you're watching the outburst of a heartbroken little boy. And young Georgian actress Nutsa Kukhianidze is just about the most charming presence the movies have seen in the last couple of years. She seems all limbs, with her exquisitely long neck and bowl haircut giving her head the shape of a delicate mushroom. She speaks in the most extravagantly bored deep voice since Eszter Balint sang the praises of Screaming Jay Hawkins in Jim Jarmusch's "Stranger Than Paradise."

Jordan has been very smart to conceive of Anne as an essentially good-hearted tough cookie. He gets rid of the misogyny of his source. When a young woman betrays the hero of the Melville film it's for no reason other than honoring the noir convention of woman as duplicitous Eve. Some of this movie's most intricate plotting -- and some of the way it confounds expectations -- centers on Anne, and Jordan doesn't do either his character or his actress wrong, allowing Kukhianidze to make her way through the movie like a languid breeze.

The biggest acting surprise comes from Ralph Fiennes, who shows up in two scenes as a shady dealer in stolen art and who has more sexiness, vitality and presence than he's ever shown. It's Fiennes who encapsulates the movies when, assessing a Picasso painting and pointing to its borrowings from Ingres and Modigliani, gives it the accolade, "He was a good thief." The movie is an ode to the joy of thievery, both for the characters and for Neil Jordan. He's lifted Melville's movie, as well as the lurid and glamorous conventions of noir, to pull off his own ingenious heist. Johnny Hallyday may know how to rock but here he gets it wrong. Noir isn't quite noir in "The Good Thief." It's more like a creamy cup of hot coffee with a shot of good bourbon on the side -- invigorating, relaxing and ending with a warm mellow kick.

Shares