"Ripped from the headlines."

That's the phrase NBC uses to promote its drama "Law & Order." On the short commercials plugging this week's show, the announcer sensationally enunciates the line, as if to suggest that because the fictional show takes its inspiration from real life, the program will be even more dramatic.

That might have been convincing before Sept. 11, when terrorist attacks destroyed the World Trade Center towers live on television. There, of course, we saw headlines come to life in the most unimaginable ways during typically perky morning news shows. The footage wasn't "just like a movie" or really like anything we'd ever seen on TV before, except perhaps for footage of events like the Challenger explosion. This was real-life drama with incredible real-life consequences playing out on our screens a few seconds at a time. The headlines were writing themselves with a cathode ray tube.

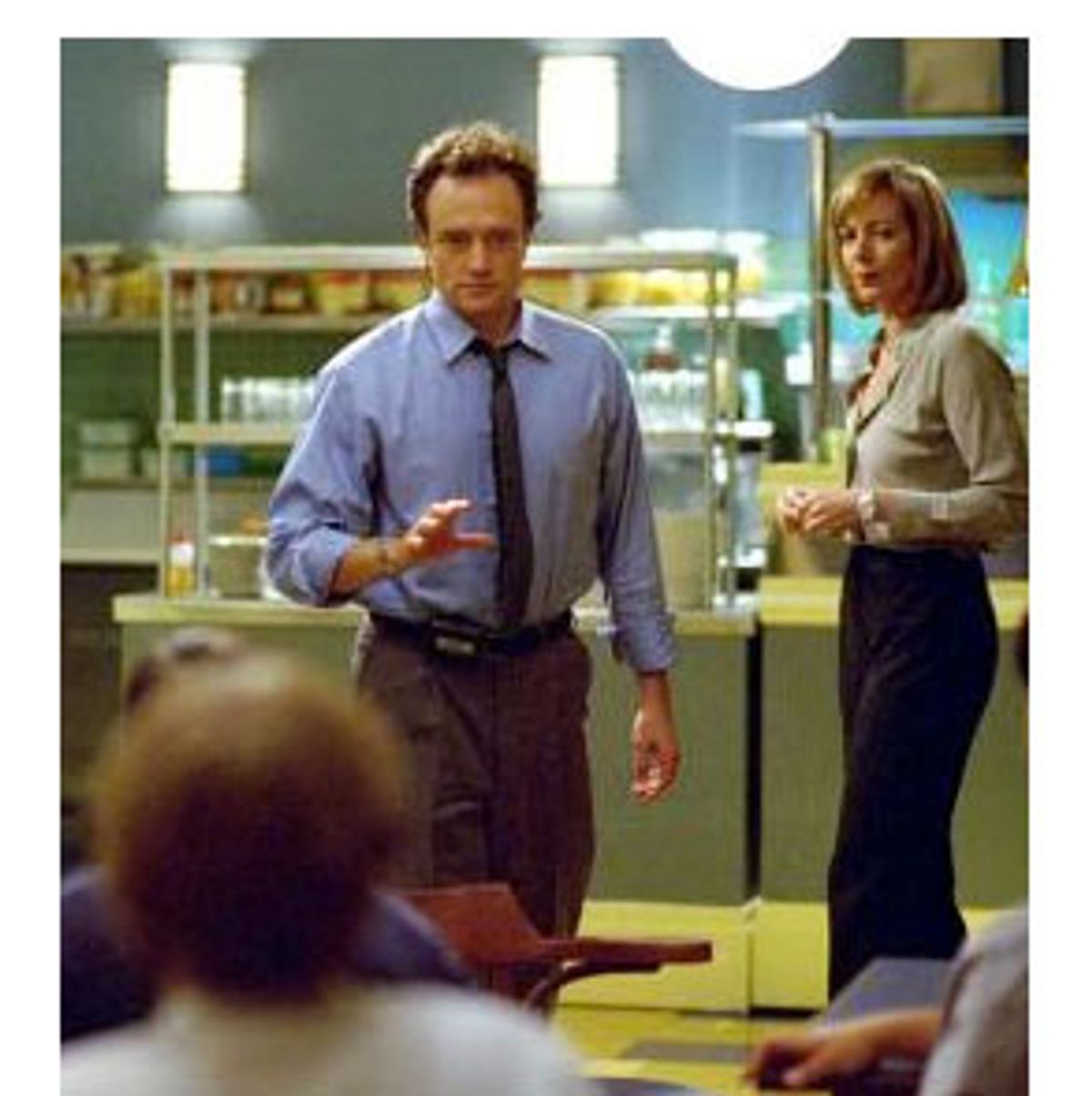

This Wednesday night, the only drama on TV that has truly been ripped from the headlines -- or at least the headlines we've seen in the last three weeks -- is a "very special episode" of "The West Wing." Unlike the "Law & Order" spot, "The West Wing" is being promoted by a solemn commercial featuring stars Martin Sheen and Bradley Whitford. "In the wake of the events of Sept. 11, we decided to postpone our premiere," says Whitford. Sheen continues, "We wanted to set our continuing story lines aside for a night and try something different. We hope you'll join us on Wednesday, Oct. 3, for this new episode." Titled "Isaac and Ishmael," the episode finds the staff of "The West Wing" "dealing with some of the questions and issues currently facing the world in the wake of the recent terrorist attacks on the United States," according to NBC. Series creator Aaron Sorkin wrote the hourlong show, which was rushed into production last week -- so fast that there were no screening tapes available for critics.

While "The West Wing" will be the first fictional show to deal with the terrorist attacks, it's not the first show to acknowledge them -- or to react. Other shows quickly made changes. CBS's CIA drama "The Agency" dropped its pilot, which began with a hostage gagged with an American flag being blown up in Cairo. "24," a new Fox show that was shot in real time and will unfold an hour at a time throughout the season, edited out of its first episode a bomb exploding on a commercial airplane. Scenes of airport troubles were deleted from the season premiere of "Friends," and "Law & Order: Special Victims Unit" reportedly removed shots of the twin towers from the show.

The first entertainment shows to come back on the air after the attacks were the late-night talk shows, but they weren't the same as they'd been. First David Letterman returned, teary-eyed alongside an also-shaken Dan Rather; a somber Jay Leno came back the next evening. Later, an equally choked-up Jon Stewart delivered an unexpectedly poignant and moving monologue at the beginning of the normally biting and satiric "The Daily Show."

Although soap operas have returned to their daytime slots and laugh tracks are again resounding during prime-time comedies, television has a different tone. And while some of the changes made in the name of sensitivity seem like overreactions, the decisions generally make sense in the context of the unimaginable events of Sept. 11. Watching a jet blow up just to make a suspenseful drama a bit more entertaining has a different meaning now. But what happens a month, six months or a year from now? Will TV and pop culture ever be the same?

In the past decade we've witnessed the rise of nonfiction and nonfiction entertainment. We dive into memoirs and personal essays, and even eagerly read biographies of almost-forgotten presidents. On television, first came talk shows, brash representations of fringe America that we couldn't turn away from. Then game shows made a resurgence in prime time, finding audiences rallying around an individual contestant and playing along in their living rooms. Somewhere in the midst of all this, documentaries sprang back to life. "The E! True Hollywood Story" introduced us to the gritty back stories of our real-life cult icons, and later we tuned in to follow Crocodile Hunter Steve Irwin, as he inexplicably picked up and pissed off deadly creatures for our education. Finally, in the past year and a half -- although the format has been around for 10 years -- reality TV moved to the front of our pop culture psyche.

But now, we've collectively experienced something that was more real than anything we could have imagined seeing in person or on TV. Most of us only experienced it through our television sets and computer screens, but we watched what happened to the twin towers live -- the aftermath of the first plane's impact, the almost unbelievable footage of the second plane flying directly into the other tower and then the unspeakable shots of the towers crumbling and people fleeing mammoth billowing clouds of smoke and debris.

Television's impact and immediacy suddenly seemed more obvious than ever. We're far more used to seeing the aftereffects of disasters and catastrophes-- the destruction left by an earthquake, even the empty shell of a building left after a bombing. While traumatic, those kinds of images seem easier to deal with, perhaps because we didn't actually experience the event live.

Television, as a medium, has a tremendous ability to communicate a process, to tell stories from their beginnings to their ends and to keep us tuned in throughout. Our most captivating cultural moments have been those that we watched from start to finish; would we have sat through the O.J. trial had we not seen the bloody crime scene and the dramatic chase live on TV? Maybe that's why, after Columbine, oversimplified shows about high school life didn't get pulled off the air (although the season finale of "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" was, even though the episode was anything but simple), and post-Oklahoma City, explosions were still commonplace on TV. Although horrific, most of what the public saw from those was secondhand. Three weeks ago, though, we watched as people jumped to their deaths from atop burning skyscrapers -- and that was just the beginning.

After that collective experience via television, there's an understandable rush to change things, to change habits, to quickly airbrush existing shows and redefine the future. Adweek reports that a recent survey conducted after the attacks found just under half of those surveyed agreeing that "the attack on the World Trade Center has made me more sensitive to certain themes and story lines in the TV programs I am willing to watch." Additionally, the survey found "57 percent of respondents indicating they are now less interested in watching" reality TV shows.

The reaction is reasonable. In the shadow of something so life- and perception-altering, entertainment seems irrelevant. But, at different speeds for different people, that shadow will slowly go away. For some, escape is necessary right now; the survey also found 57 percent of respondents wanting to watch more comedies right now.

Now, in the weeks following the disaster, it seems obvious that silly sitcoms seem even more irrelevant than before. And as far as heroes go, the winners of "Survivor" aren't even on the same planet as the firefighters who raced into the twin towers before they collapsed. (Sadly, there's some crossover: The winner of Fox's "Murder in Small Town X," Angel Juarbe, was one of the firefighters who responded to the scene, and he is still missing.) And whatever actions the real president takes will be remembered far longer than whatever happens to Martin Sheen's character this season on "The West Wing."

But all of that has always been true. Wouldn't gagging someone with an American flag and blowing that person up have been distasteful before Sept. 11? Didn't "Friends" always deal with ridiculous story lines? That sudden realization by television executives has them rushing to change their lineups now, and some are forecasting the end of reality TV because of a few low-rated shows or the results of a survey. Some of the changes are small, but others could be overreactions that shift the direction TV has been moving in.

For some viewers, it may be too early to laugh with "Friends" or scheme with players on "The Mole 2." But escapist, entertaining shows aren't going anywhere. Maybe they'll remain the same; maybe their creators will be struck by a newfound sense of responsibility and change the shows' directions. Because we've never been through a national crisis with our current burgeoning entertainment world, we have no idea what this will do to today's television culture.

Television's power is that it can be both ridiculously trite and overwhelmingly real at the same time. It can show us how a snake reacts when a feisty Australian holds it by the tail, or it can teach us about our relationship to the world and the human condition through footage of a crumbling building. And they don't cancel each other out.

Shares