Sexual tourism is a red-hot button on the scale of politically correct travel. While ostensibly about pleasure, jetting off to partake in exotic, erotic smorgasbords for a price is an activity that taps directly into deeply ingrained perceptions of gender, race and uncomfortable global intercourse between First, Second and Third World cultures. For San Francisco Bay Area photographer Reagan Louie, this rich territory, spiked with ideological land mines and oases of sparkling female beauty, serves as something more complex and ambiguous.

As a second-generation Asian American, Louie has made a personal and artistic practice of traveling East in a photographic search to reclaim his roots. In the 1980s, he visited his father's birthplace in China, creating a visual record of the eye-opening, vibrant color pictures that for him, and many viewers, create a link between China and Chinese American identity. "A psychologist might say that my search had been caused by 'cultural marginalization,'" he wrote of that series, "In Search of a True Life" -- something that for him became an ongoing project about postcolonialism.

In the mid-1990s, during picture-gathering trips to Asia, Louie homed in on the sex trade, which is the basis of his recently released book, "Orientalia," as well as an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, "The Photographs of Reagan Louie: Sex Work in Asia" (through December 17).

These are portraits of women in China, Japan, Thailand, Korea and Southeast Asia that, for the artist, express a dynamic of Asian male sexuality as seen through images of women. The pictures are crisp and colorful visions of clothed and unclothed prostitutes -- hostesses in karaoke bars, masseuses, or employees in betelnut kiosks or glassed-in shacks on roadsides that sell various pleasures to go. Sometimes these women are seen with men, but more often they look to the camera and, by extension, to the photographer from a difficult-to-read position. As SFMoMA curator Sandra Phillips describes them in her wall text, the pictures "offer a dispassionate examination of a topic that is both controversial and conflicted."

This is the angle Louie takes in conversation about his art. "All my work is about how society shapes an individual to some degree," he says. "The first time I went to Asia in 1980, I experienced a different kind of dynamic between men and women. Not that we [Asian men] are exactly emasculated in the U.S., but we're somewhat neutered. Asia has very masculine societies; men have a dominant role. I was aware of it from the beginning, but I didn't know what to do with it."

His first-ever visit to a sex emporium in Hong Kong, where he was shooting during the hand-over from the British in 1997, was an eye opener that jumpstarted the project. Louie, a family man with wife, kids and a dignified job as a professor at the San Francisco Art Institute, entered a new world that offered very distinct examples of the gender dynamic.

"Asian men and their interactions with the sex industry are like a frat party; there's a lot of joking around and playfulness. It's not just about sex -- there's a full sense of socialization. It's a very Asian thing, and I saw it often in different countries. " The primary venues, he says, are karaoke parlors with private rooms. A photograph taken in China in 2000 depicts such a scene, with three women smoking, singing, eating and drinking with a couple of men in what looks like a living room but may be a private karaoke chamber in the Enjoy Business Club, a glitzy, neon-trimmed establishment photographed elsewhere in the series. The image is far more social than salacious. In another, perhaps taken in the same location, a man and a woman chastely croon together while watching the video screen.

More often, the pictures are of women on their own or in an artistic encounter with the photographer. Few of the models look directly at the camera -- their indirect glances serve as a protective mark of professional distance. "I'm shy," Louie admits. "The camera allowed me to enter those places and to meet those people."

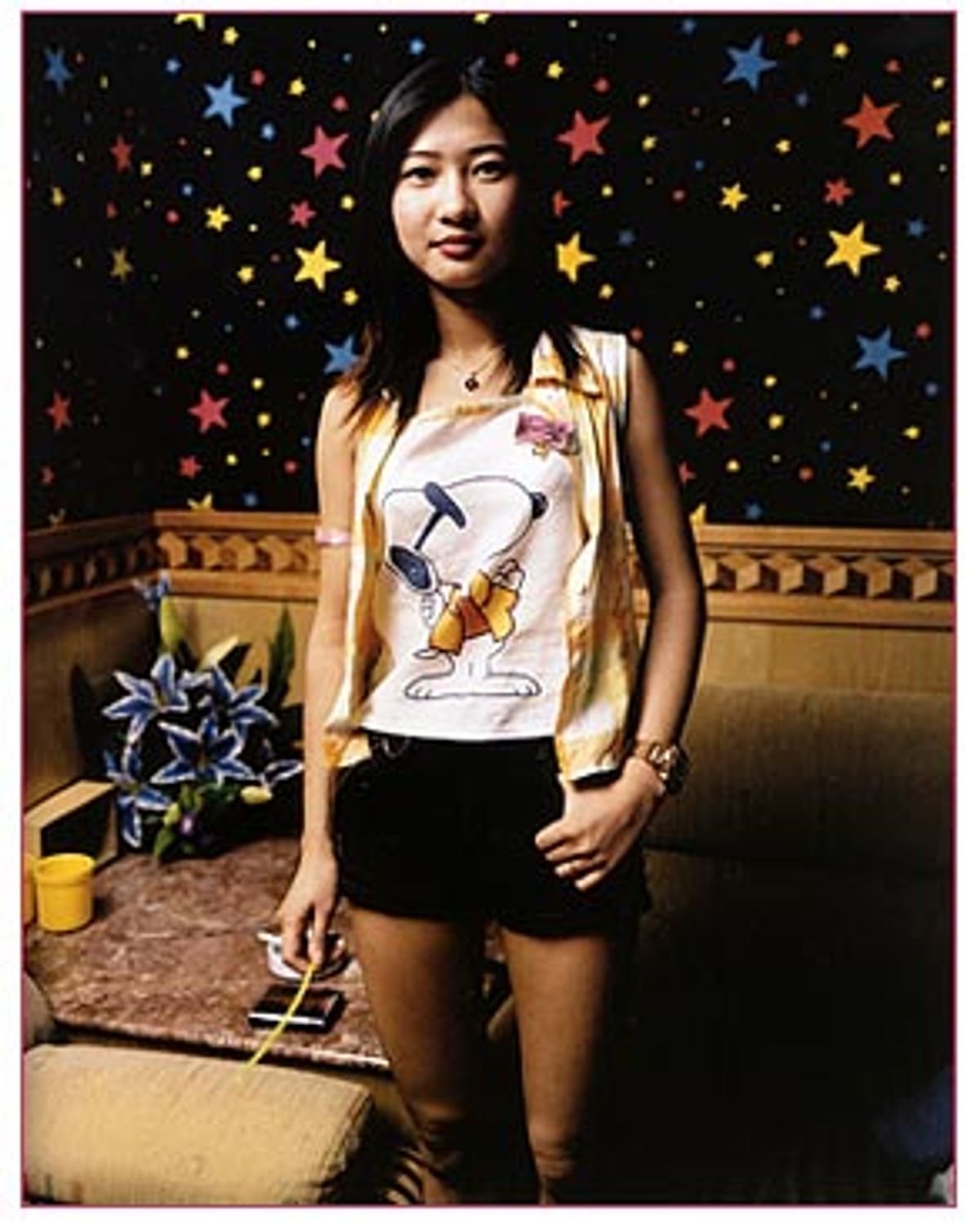

Once inside, he finds multiple layers of social evidence. He photographs a Chinese bar girl named Ting Ting in front of star-patterned wallpaper. She appears to be in her early 20s and is wearing a miniskirt and Snoopy T-shirt, an element that subtly introduces a specter of Western influence (evidence that appears frequently in the photos). It takes a moment to notice the tag that reads "N-30" taped to her shoulder, clearly a number identifying her as merchandise. It's not easy, however, to discern her internal state as her expression is a blank, vague smile, and the lighting is at a professional level that eclipses a sense of documentary spontaneity. This, like all the others, is clearly a posed picture.

There's a similar quality to the much raunchier "Yuan Yuan, Macau," a 1999 hotel room scene that depicts a nude woman sitting in a chair, matter-of-factly exposing her genitalia. Her head is tilted back slightly into the executive-gray curtains, her face made up and her eyes hidden beneath stylish wire-rimmed sunglasses. The picture, in some ways, addresses the difficult dichotomy between body and mind with an almost shocking brazenness.

Such images raise lots of difficult questions. Are these women being demeaned or empowered? Are they exoticized or exploited? The ambivalence is much of what makes these pictures interesting, as is the way that they are framed both in the book and the exhibition.

"I didn't do anything furtively -- without the girls there would be no pictures. I paid them for their time, which introduced a collaborative nature. Most of the pictures are staged -- the women arranged themselves for the camera." Clearly the notion of the artist entering an economic transaction with a model parallels the usual parameters of the hooker/john interchange. It's a thorny, provocative aspect of these pictures that raises the obvious question: Did the artist partake in the services on the menu? Louie responds coyly: "Is taking pictures a form of sex?" Was he even tempted? "Sometimes they're sexy, they're good at their job. They know how to draw a man in.

"I'm full of contradictions and conflicts," he continues. "I implement myself, but it's not a 'Heart of Darkness' vision. I wanted to depict survivors, not victims."

Louie is quick to point out, in the standard porn terms, that all the models are over 18 (at least that's what they told him), and he's wise to avoid that political quagmire. But his project doesn't completely skirt potentially controversial topics. There are images that depict interracial desire -- a white woman with a Japanese man, an Asian female with a white man in Hong Kong -- as well as ones that point to aspects of community, commodity and fetishized identities. Louie doesn't attempt to cover all the bases. He doesn't photograph male sex workers or offer a critique of sex tourism -- an aftereffect of global capitalism that often illustrates incredible international inequities and the enduring specter of racial stereotyping. He's aware of all these things, but in the end, he admits this is more the product of an artistic vision, something that began to fascinate the artist and consumes him. He leaves the theorizing to others, especially other artists, whose work he has included in his own show to provide a historical context. Pictures by Picasso, E.J. Bellocq (famous for his early 20th century portraits of New Orleans whores -- see Brooke Shields in "Pretty Baby"), Cindy Sherman and Japanese photographer Yasumasa Morimura offer other takes on the sex industry.

Another to whom Louie turns is self-proclaimed "activist hooker" Tracy Quan, whose iconoclastic opening essay in "Orientalia" challenges various mainstream readings of the business, mainly the zones between selling fantasy and the realities of carnal commerce.

Quan writes that her job is "about enchantment, not just service." She feels a profound sense of shame when she learns that the pricing system at a Hong Kong brothel, as seen in a sign in one of Louie's pictures, is predicated on ethnicity (Malaysian and Philippine women go at bargain basement rates). Yet she also admits to identifying with the fantasy of Julia Roberts in "Pretty Woman," and weighs in on the side of pleasure over politics. She admits, for example, that for those low-priced women she hopes "not for 'social justice' ... but the outright privilege of being a special, exotic treat."

She has more pointed opinions about the hegemony of feminism. "I envy the prostitute who hasn't been confronted daily, as I was from an early age, with feminist attitudes and ideologies," writes Quan. "When I look at these pictures, I imagine that these women are much freer because they are not bogged down by feminist arguments."

Such statements seem constructed to deflect criticism, but may also fuel the show's controversy. "What does it say about the current dialog that they're contextualizing these photographs with the words of a strong, activist hooker's voice who doesn't necessarily identify with feminist or activist concerns?" ponders Tina Takemoto, a professor of visual studies at California College of the Arts in Oakland. "Would these pictures still be interesting without Quan's statements?"

"Without Tracy's kind of progressive view of sex workers, I couldn't do this project," Louie admits. "I chose to do this work to explore if an artist could successfully take on a loaded subject like that on its own terms, and not sugarcoat it." Some will argue that Louie's extremely glossy pictures, presented in the museum in an impressive, life-size scale, do just that: put a plastic product sheen on a complicated situation.

Ultimately, it's these unresolvable questions that make Louie's project memorable. It's impossible not to be seduced or rankled by them, and to clarify our own stance in relation to the issues. "At the end of the day, you have to give shape to your own experience," Louie says. "I work very intuitively. I wasn't calculating that I was going to find my roots, I just take the pictures and follow their lead."

Shares