When I was about 10, my older brother sometimes called me "Pug." I didn't like it, but it never really galled me the way my brother hoped it would, because as insults went, "pug" was pretty tame. This was the '70s, when the black-is-beautiful movement was in full swing and my light complexion and fine hair -- which could never muster enough kink to be whipped into the requisite Afro -- made me worry that I wasn't black enough; my broad nose actually helped counter that worry and kept me in vogue. Of course, this new affirmation didn't mean that a certain ancient self-hatred had disappeared entirely, but black people at least seemed to have evolved past the musty obsession with chiseled noses as the chief standard bearers of beauty -- something I grew up associating with all those tragic-mulatto potboiler novels from the late 19th century in which the secretly black heroine's aquiline nose was like a talisman that always protected her from harm and preceded her in good fortune.

Now history may be cycling back on itself, with some intriguing modifications. In March, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons -- with 6,000 members the largest plastic surgery organization in the world -- publicized a study that appeared in its medical journal, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, about new techniques in reshaping the African-American nose. The study, "Rhinoplasty in the African-American Patient," advanced a novel-sounding theory that nose jobs for blacks are now less about diminishing ethnic appearance than about preserving it. Anticipating the skepticism that lay people like me might feel, the association quickly detailed its position. It explained that the timeworn European standard of beauty "has stepped aside, encouraging African-Americans to retain their unique ethnic characteristics while improving their overall look." The pitch contended that "with this shift in attitude, plastic surgeons who appreciate ethnic concepts of beauty and the unique anatomic characteristics of the African-American nose can create the most consistent and best results."

Good self-empowerment language, but I wasn't convinced. This didn't sound like progress, but American hucksterism at its most conniving. It looked like the ultimate in having it both ways, the plastic-surgery equivalent of a Ginsu knife ad that promises to cut ferociously and never hurt countertops. It also still felt like a massive fundamental contradiction: Why would a black person interested in preserving his or her ethnic identity consider having a nose job at all? Why would a plastic surgeon who embraces ethnic concepts of beauty want to make those alterations?

The lead author of the study, Dr. Rod Rohrich, chief of plastic surgery at the University of Texas in Dallas, insists the premise is both aesthetically logical and racially ethical. He sees plastic surgery not as a tool of black assimilation -- that's old school -- but as a means of individualization, of sculpting each nose in proportion to each face to achieve what he calls "nasal-facial harmony." Rohrich, who is white and who has been performing rhinoplasties for 15 years, says he won't straighten a black nose unless the patient has angular features to match. When doctors do graft a Northern European nose onto a black American face, it results in what he diplomatically calls "racial incongruity" (and what the rest of us might call Michael Jackson syndrome). With nose jobs among blacks on the rise -- which the ASPS can support only anecdotally -- Rohrich believes the time is right for surgeons to take a more nuanced approach to altering black noses, for the good of the profession and patients alike. "Too many surgeons just give people what they want without considering what's best for them," he says, with some distaste. "But I won't give somebody a pencil nose just because they ask for it."

I don't doubt Rohrich's sincerity or the assertion that nose jobs are actually becoming more enlightened (I can see the "Oprah" promo already). But my initial suspicion of black folks getting nose jobs holds. It's difficult for me to believe that anybody black getting their nose done isn't doing it to some degree to look more white and less black -- such is the still considerable burden of history. Because of a tortured struggle for mainstream acceptance that began with slavery and has never ended -- drugstores still sell skin-lightening cream in the beauty aisles, after all -- changing black faces is almost never a purely aesthetic consideration. As they are so often in matters of appearance, racial considerations are never far from the surface.

Plastic surgeon Julius Few understands the maddening complexity of what should be superficial and straightforward -- a nose job -- though he's optimistic, like Rohrich, that the "self-hatred" stigma of the procedure has abated to the point that most blacks reshaping their noses are, like the majority of rhinoplasty patients, merely correcting anatomical inconsistencies. Few, who is black and an assistant professor of surgery at Northwestern University in Chicago, praises the study and says that, given that nose jobs among blacks are increasing, this is an opportune moment to promote the validity of whole black facial aesthetic. "We [blacks] grew up believing that seeking out plastic surgery was tantamount to wanting to be more white," says Few. "But with increasing information on this subject, blacks can achieve what other groups have long had" -- plastic surgery without the stigma of ethnic loathing -- "and understand they're not doing anything against their upbringing."

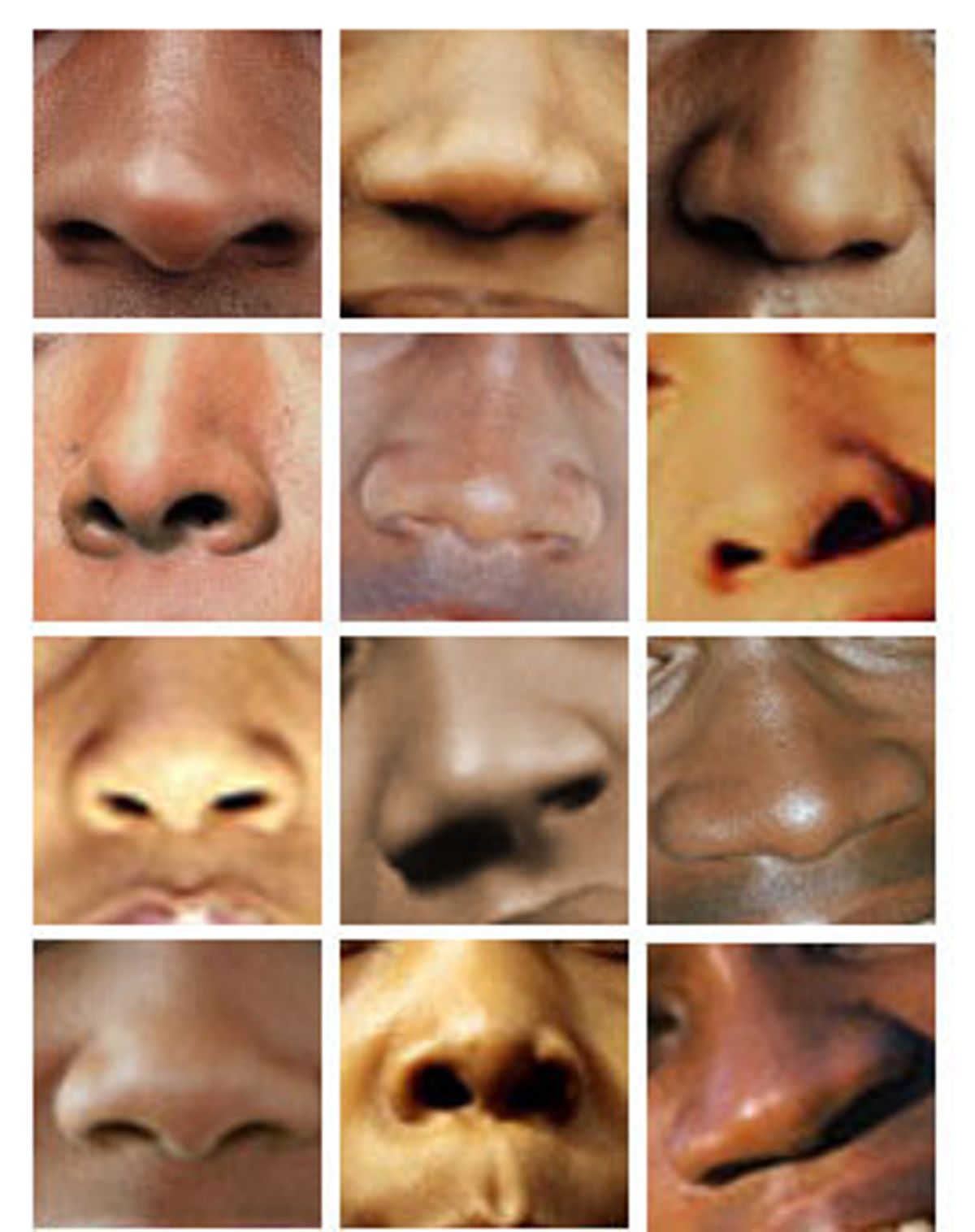

In the photos of pre- and post-op black patients included in Rohrich's study, the women did wind up with noses true to their faces -- nasal-facial harmony prevailed. But frankly, I didn't see much disharmony to begin with (this despite the women looking a bit haggard and bare faced in the "before" pictures, nicely made up and hair-doed in the "after" ones -- an old fashion-magazine makeover trick to heighten contrast where too little exists. And the fact that the "after" photos invariably featured lighter, brighter complexions and straighter, neater hair should be lost on no one.) Sure, I'm making aesthetic judgments here -- one person's bothersome pug nose is another's perfection. Yet ironically, those photos reminded me that black faces can better accommodate broad noses -- the so-called imperfection that the plastic surgeons are targeting -- and so it makes less sense to change them. But cosmetic surgery is predicated on ideals, which are elusive at best, unattainable at worst, and always in the eye of the beholder. "We don't really judge," says Barbara Porter, Rohrich's assistant. "We just want to get the problem straightened out." So to speak.

More than one of the photos revealed altered noses that were narrower and more pinched -- not quite faithful to the original and not Michael Jackson either, but something in between. It is that gray area that plastic surgery is really good at staking out and that black people, like all other people, probably want: a change that is better than nature, but not obviously so. Blacks, who according to the ASPS make up 6 percent of all plastic surgery patients, may be more inclined than most to want to triumph over that nature, given that their looks have historically been used against them and been such an integral part of their oppression. Rohrich's study unwittingly evinces that oppression in the medically dispassionate descriptions of the typical characteristics of a black nose: "Broad and flat dorsum," "Slightly flaring alae," "Ovoid nares." It detailed one patient's complaint of having a nose that was "large and unrefined" -- a common complaint that always involved flaring alae -- which a surgeon transformed into a "narrowed, more refined nose with improved tip definition." The study is commendable for putting the phrase "African-American beauty" in a sentence more than once, but it is a beauty still clearly searching for mainstream context. Few admits he winced at the descriptions himself because it made blackness feel like something not to celebrate but to overcome. Few hopes that his field, the last place anyone would look to for reinforcing the idea that natural is best, will in fact do just that. "Medical technology doesn't make black noses sound attractive," he says. "But they are. They have an inherent beauty."

Certainly they do -- that's what we've been telling ourselves since the '70s. I personally don't know any blacks who've fixed their noses or plan to. The procedure (which costs about $12,000) is perhaps being done more frequently though not more overtly, which may mean that blacks still fear that their inner tragic mulatto could rear its ugly head at any moment. As for me, I'm still pretty content with my pugness. Not only does it harmonize with my face, but it also helps me assert myself racially and otherwise -- when I get mad, nothing makes the point better than flaring alae. Of course, I still have misgivings about the size of my butt. But that's a final frontier in the black-image war that may be a few years -- and a couple of cosmetic-procedure trends -- in the future.

Shares