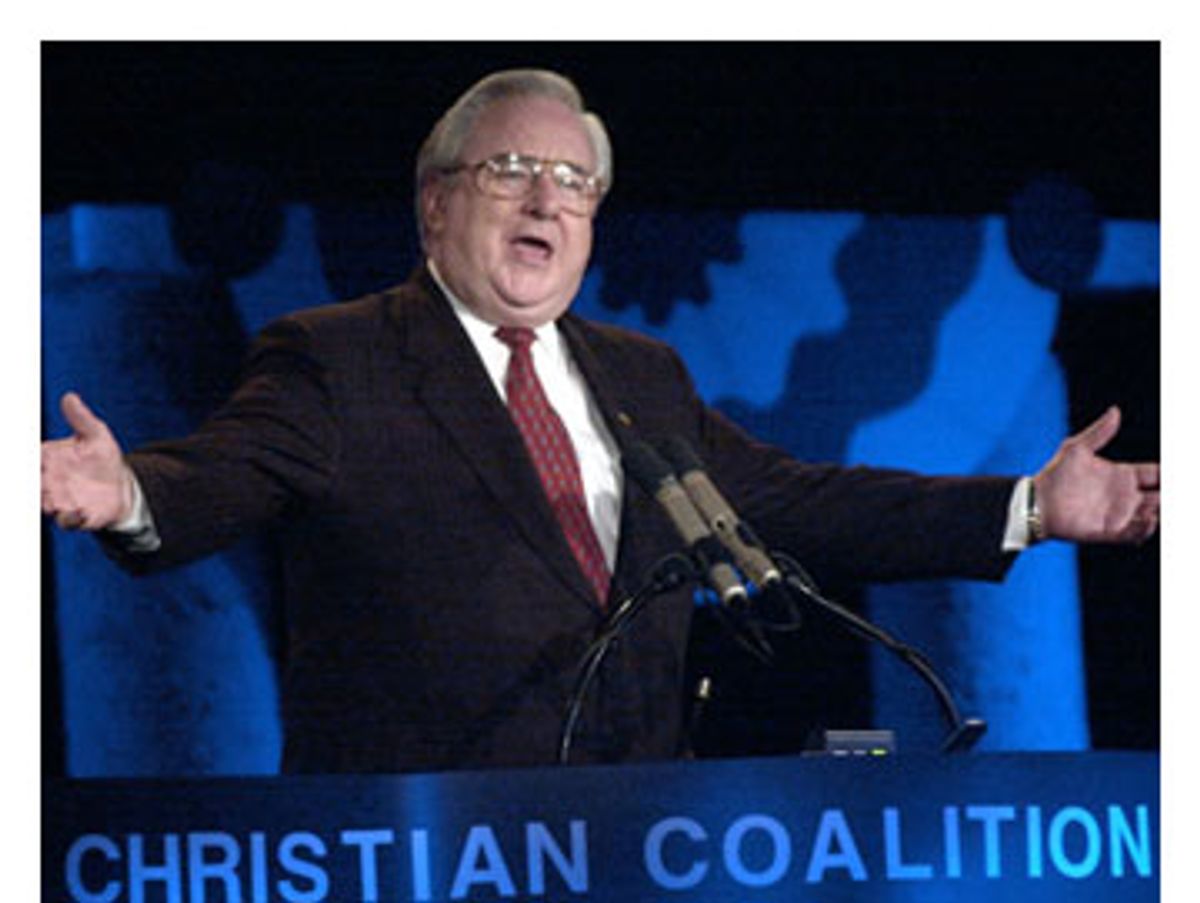

One never wants to speak ill of the dead, but in the case of Jerry Falwell, how can one not? Falwell will always be remembered for his "700 Club" comment in the wake of Sept. 11: "I really believe that the pagans, and the abortionists, and the feminists, and the gays and the lesbians who are actively trying to make that an alternative lifestyle, the ACLU, People for the American Way, all of them who have tried to secularize America, I point the finger in their face and say 'you helped this happen.'" Even though Falwell later apologized, the damage had been done: A sacred moment had been used for profane purpose.

And that, really, is Falwell's legacy. To the religious life of the United States he made no significant contribution. But to the political life of the country, he made one: He founded the Moral Majority. In so doing, Falwell managed to take something holy -- one does not have to be a Christian to admire the life and teachings of Jesus Christ -- and turned it into something partisan and divisive. Falwell, the quintessential conservative Christian, was always more conservative than Christian. To the extent that history will remember him, it will be as a politician, not as a preacher.

Even Falwell's political contribution, despite the success of the Republicans during the Reagan years, left a mixed legacy behind. But the Moral Majority disbanded in 1989, prompting the inevitable thought that Falwell's ideas were neither moral nor in the majority. The movement of conservative Protestants into the base of the Republican Party was far too important a task to be entrusted to a man as oblivious to public relations as Falwell. Once the Ralph Reeds and Karl Roves took over the task of blending religion and politics, there was no room for Falwell. Longing for Washington, he had to settle for Lynchburg, Va.

But then there was cable television, the perfect medium for someone as shallow as this man. Falwell appeared so many times on cable news that one tended to forget how little influence he actually wielded. Had it not been for cable television, Falwell would have been forgotten long ago (and I would not be writing about his legacy). He was perfect for the world created by Fox: extremist, polarizing, Manichaean. (The Manichees, a Persian sect that for a time attracted the great Saint Augustine, adhered to a black-and-white reality in which evil was always in an endless struggle with the good.) Five minutes of hate followed by a commercial break: It is not a format fit for all, but for Falwell, it fit like a glove.

Conservative Christianity has been trying to recover from Falwell for the past two decades. Just as his political views were too buffoonish to make the Moral Majority a reality, his religious sensibilities were too shallow to spread evangelical Protestantism. Evangelicalism grew in the exurban megachurches, and the megachurches, implicitly and occasionally explicitly, rejected Falwell's approach to the faith. Rick Warren, Joel Osteen, Bill Hybels -- these inclusive preachers inherited the mantle of Billy Graham, not Falwell and his great rival Pat Robertson. With the maturation of American evangelicalism has come an interest in social justice, environmentalism and peace. The people who represent evangelical Protestantism's future want little or nothing to do with injustice, pollution and war.

Of course America's megachurches offer a thin theology equivalent to 12-step therapy. But Falwell's contribution to American religion was even less than that. Falwell's university -- Liberty University -- never achieved anything resembling serious academic status, although it did produce a decent enough basketball team. Falwell's church, Thomas Road Baptist Church, with its Scopes-trial era insistence on hell and damnation, was not what American Christians wanted to hear. Falwell's 1980 book, "Listen, America," is an embarrassing string of clichés. "Sin is a transgression of God's law and God's law is unalterable," Falwell wrote. "To sin is to voluntarily disobey God and His divine laws." But it was not the sinfulness of human beings that preoccupied Falwell; it was the sinfulness of the country in which they lived: "Sin brings reproach upon a people. This is the reason we are in a nosedive as a nation." Less than 50 years after the defeat of Nazi Germany, Falwell could write of America that "we have become one of the most blatantly sinful nations of all time." Falwell's theology, such as it was, never made clear how America could be both the promised land and Gomorrah at the same time.

Instead of pondering Jerry Falwell's legacy, we would be better off asking how this man ever became a public figure in the first place. America has had more than its share of religiously inspired demagogues -- Dr. Fred Swartz, Billy James Hargis, Carl McIntyre come to mind -- but they are forgotten figures, marginal even to the times in which lived. One would like to believe that the United States has become a bigger and better country since the days when men like them preached about captive nations and denounced the pernicious influence of rock 'n' roll. But then there is Jerry Falwell. In death, as he did in life, he reminds us that demagoguery never dies; it just changes its form. Jerry Falwell expressed great hate for a lot of his fellow Americans. It is no wonder that so many of them will greet his death with something less than love.

Shares