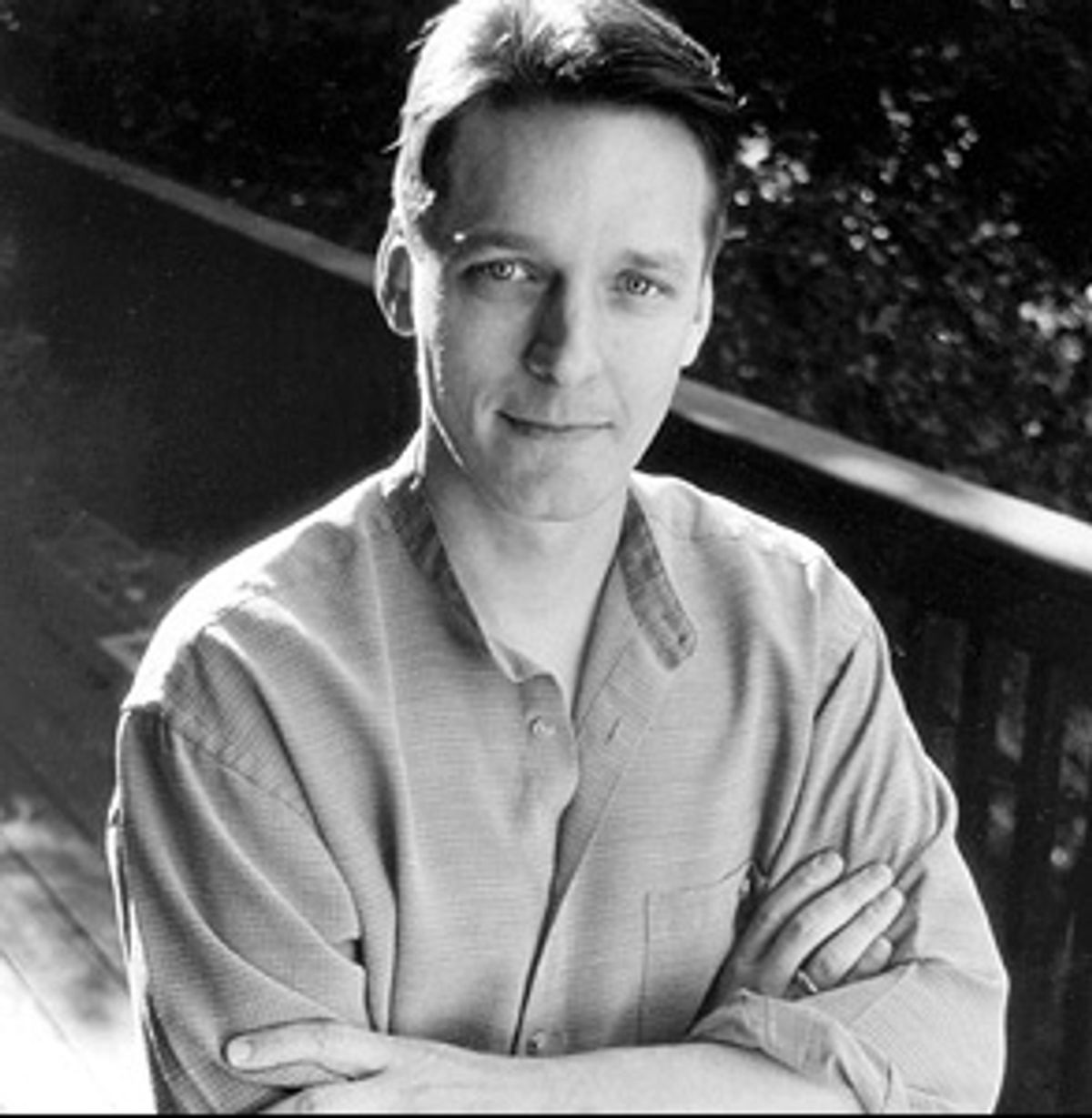

It strains believability that Mark Salzman has produced a book that captures the inner life of a middle-aged, cloistered Carmelite nun. The guy is an agnostic. As a graduate of Yale, a celebrated author since his 20s, an expert martial artist and an accomplished cellist, he enjoys a privileged spot among the cultural elite. To make matters worse, he now lives in that swamp of earthly delights, a sunny Los Angeles suburb, and has a wife in -- what else? -- the film industry. He's even been blessed with golden-boy good looks, which were fully exploited when he played himself in "Iron and Silk," a film based on his post-college memoir about teaching English in China.

So Salzman is an unlikely renunciant. He seems to love the world's many temptations too much to shut himself away in pursuit of an illusive higher goal. Yet that's exactly what happened. In the process of writing his unearthly new novel, "Lying Awake," he became a sort of literary penitent. For six grueling years, as he sat down each day to work on the book that he felt was failing miserably, he experienced his own version of St. John of the Cross's dark night of the soul. He wrote and rewrote -- adding first years of research then cheesy love stories to appeal to imagined masses, all the while listening to his agent's disappointed comments. His home office with its cats and other distractions bothered him so much that for a full year he cloistered himself in his car, a towel wrapped around his head to muffle sound. Demon-like, the cats pursued him, sitting on the car sunroof and delivering a graphic reminder of his place in the universe.

Finally, after he'd decided to admit defeat, he went off to a writer's colony to do nothing and think about his next book. It was there he had an epiphany that allowed him to sit down and rewrite the book from scratch in five weeks. The grand realization? He wasn't so different from his main character after all -- his faith in writing was every bit as illusive and irrational (and almost as sacrificial) as his character's burning faith in God.

In the wake of publishing this book, Salzman created not one but two stories. The novel is about a nun who learns her religious visions and channeled poetry may not be ecstatic gifts from God so much as symptoms of temporal lobe epilepsy. Her conflict revolves around choosing between physical health and the psychic fireworks she has come to associate with her relationship to God. The other story, which he's turned into a performance piece and used as a marketing tool to sell the book, is about the tortured novelist who endures hell until he experiences a transcendent empathy with his own protagonist.

If the allegory of the struggling writer as devout mystic sounds a little self-inflating, it doesn't feel that way when you listen to Salzman detail his humiliations. In a culture enchanted by the pains and pleasures of the writing life, the tale of the self-mortifying novelist is a familiar one. But rarely does the story have such an inspirational ending, because Salzman's book feels so genuinely the product of miraculous forces.

Salzman spoke with Salon about the spirituality of doubt, the pleasure of well-earned fame and stalking a cloistered Carmelite nun in New Mexico.

I've read that you consider yourself an agnostic. How did you come to write a book that takes place inside the head of a Carmelite nun?

I don't really know! I can tell you the history of the beginning of the idea: It started after I read an essay by Oliver Sacks about temporal lobe epilepsy where the person would experience an intensification of interest in religion and spirituality. And I thought: What if somebody already committed to a religious life discovered they had this disorder and they had to make a decision about whether or not to be cured? I did research into the various contemplative orders and I discovered that Teresa de Avila -- the founder of the Carmelite order -- had all sorts of terrible illnesses and headaches along with her visions and so she was a possible candidate for having epilepsy. I thought, Wow, if the founder of the order had this disorder, you couldn't do any better than that.

Then I had to learn about Catholicism, which was a lot more involved than I'd thought. I read the mystics and essays about the Carmelites, but it was only when I started talking to real Carmelite nuns that my understanding of their lives changed.

It seems the Catholic contemplatives have been experiencing a renaissance -- Hildegaard von Bingen is selling millions of CDs; people are reading the mystical poets. What do you think it is about these characters that speak across the centuries to people who don't even hold their beliefs?

I think it's because the mystical traditions deal with doubt more than a lot of other religious people. It's true of Thomas More and St. John of the Cross, and true of the contemplatives in general. They put the struggle with doubt right in the forefront of religious experience. They say that it's when you think you know God that you're farthest from knowing him.

We live in an age when certainty is passed off as spirituality -- like the fundamentalists who are so sure of their beliefs -- and what I love about the contemplatives is that they are willing to acknowledge their doubt.

One of my favorite moments came when I was talking to a Carmelite nun and I asked her what she struggled with most and she said: "Doubt as to God's existence. Every day we're searching for God -- you have to confront that you have doubts."

So it appeals to those of us that think we don't know the answer.

How did you research the book?

The neurology side was much easier and that was a lot of fun. I read essays and talked to neurologists. Learning about the religious side was much more difficult. Of course I did all the reading, but it took several years to meet with a Carmelite nun. There was one person -- a prioress in New Mexico -- who took a real interest in the book. As the friendship developed between us, I had a human model of what a cloistered nun might be like.

What were your conversations with her like?

We sat in a parlor on either side of a barred window. What surprised me was how much fun the conversations were and what a great conversationalist she was. I pictured someone who wasn't used to talking and was nervous or awkward but it couldn't have been farther from that.

Unlike the nuns in the teaching orders who experience a lot of tension between their religious ideals and the outside world -- the stereotyped strict nun -- I think the cloistered nuns seem more relaxed because they have both feet in the cloistered world.

The prioress asked me, "Are you Catholic? Are you religious?" and I said no, and I thought that she would say, Well, we feel uncomfortable about you writing about this. But instead she said that's not a problem at all.

How did you find them?

It's kind of a wonderful story. I was having trouble finding any Carmelite nuns -- I got an address of an abbot in New Mexico and he invited me to visit his monastery. [While I was there] I took a walk and I found a road that had a sign for a Carmelite monastery. I decided to walk down the road to the monastery and knock on the door.

And a voice answered: "Praised be Jesus Christ, may I help you." I explained that I was writing a novel and wanted to talk to a nun. She invited me to go into this little parlor. And she drew back the curtain to look at me and said, "I thought a novelist would be older."

The book takes place in the present in Los Angeles rather than 16th century Europe. Was this based on some factual Carmelite mission?

No, but it's surprising: There are often cloisters tucked away in cities ... And interestingly enough there are more young people interested in cloistered orders right now than the so-called modern orders.

Did your own vision of religion and religious people change in writing the book?

Absolutely. I'd always felt that there was a real gulf between those who were religious and those who weren't. People who devoted themselves to a faith -- it was always so foreign to me, I couldn't grasp it. But through the crisis that I had in failing to write the book, I realized that there was a connection between my faith in art and their faith in God. I take it on faith that art is worthwhile and that it's good for the world. But it's not rational. My own struggle to maintain faith in my writing is the same process so it gave me a sense of kinship with these people. It's so much more familiar to me now.

There's a theme in much of your work about wanting to be good at something. In "Iron and Silk" you confess this desire to one of your Chinese friends. But in some way Sister John is struggling with the same desire -- in some sense she wants to be good at her calling: to be totally unselfish. Yet ironically, this is also a selfish desire in some way -- or at least she suspects it is. Do you think the desire, say, to be good at martial arts is roughly equivalent to her spiritual ambitions?

A better comparison would be my early interest in Zen Buddhism -- and the idea of becoming enlightened. I thought it would make me datable. You want something that's really transcendent but you also want something for yourself and it's sort of a contradiction. The same is true of wanting to become holy --

I do think that's a universal problem with reaching for an ideal. You feel called to move toward it and you reach for it but fall short. What's the point? It's a recurring theme and one of the great challenges we all face being idealists and having to be realistic. And yet you've got to move on, you've got to have some kind of faith.

Talk a little about how you struggled to write this book. Did you ever grow bored with the subject matter?

By the third year, I became really confused -- I had to wear a tin-foil skirt to keep the cats off my lap and a towel on my head. Oh, it was just terrible. Now it's a good story, but my wife would be the first to say it was not fun at all. My confidence was destroyed. I wanted to give up but I couldn't. I'd invested so much in it already. I was putting her through hell. So I started again from scratch.

I decided to give up on the nun and neurologist being attracted to each other -- I threw that away and at the end of that draft, I thought, this is really good. I passed my test. So I sent it off to the agent and she said, "I missed the doctor." I went back and read it and it was bad -- she thought the problem was that I'd gotten rid of the doctor but it was that it had no real life to it. I hadn't figured out what my root of it was.

That's when it occurred to me: What have I dedicated my life to? What reason do I have to dedicate my life to art? No rational reason. So I started again.

In the end it was "easy," but after years of anguish. Did you learn anything about the futility or worthiness of "trying"?

I haven't learned anything. I'm writing a new book and really feel like [I'm] stumbling around blind. The only thing is I created a deeper reservoir of confidence. I can say: I've been here before -- don't give up. I've added to the evidence I have that when I stick to something I can make it work. And I think that's the most precious currency that writers have.

You've had a tremendous response to this book. Sister John would have been very fearful that such worldly accolades would infect the purity of her pursuits. Do you ever feel worried that your growing fame affects your creativity?

None at all -- it feels so damn good. I can imagine how there are ways success can hurt a person, if they're young. But if you've paid your dues and you get praise, then I don't see how it hurts. I'm enjoying it -- that's all I can tell you.

What are you working on now?

I'm working on a nonfiction book about teaching creative writing in juvenile hall for kids about 15 to 17, who are waiting to be tried as adults and now they're waiting to be sentenced. Most of them are charged with murder and come from the most chaotic and tragic backgrounds.

I fell into it by accident -- a friend of mine had invited me to his class so they could meet another writer and I just dreaded it. I thought, What could be more depressing? And I went down there and they were so unlike what I had imagined. They were so clearly hungry for people to take interest in them.

They had all prepared a little essay to read to me and their hands were shaking, and seeing the looks on their faces when I responded to what they had written ... The writing was amazing. So I decided to volunteer to teach my own class.

My dad was a social worker and he said do anything but don't be a social worker, it'll break your heart. So I'd always stayed away from stuff like that. Of course, there's a very serious side to it -- these kids don't have much of a future and they've killed people in some cases. These are kids who are so poorly socialized, most of them are addicted to drugs and they've been so abused by adults. And yet what we do in that class is so uplifting, I find it the opposite of depressing.

Shares