I’ve got maps on my mind again, having recently found W.W. Jervis’ "The World in Maps: A Study in Map Evolution," published by Oxford University Press in 1937. I discovered this book quite unexpectedly one recent afternoon, running errands in my Queens neighborhood. New York’s mild winter has teased out the book vendors who usually wait until spring before returning to the sidewalks with their tables. With an emphasis on Spanish-language titles and genre fiction, at first glance the books on offer appear mundane. But if you take the time to really look, something of interest is sometimes dug out of a box.

I’ve got maps on my mind again, having recently found W.W. Jervis’ "The World in Maps: A Study in Map Evolution," published by Oxford University Press in 1937. I discovered this book quite unexpectedly one recent afternoon, running errands in my Queens neighborhood. New York’s mild winter has teased out the book vendors who usually wait until spring before returning to the sidewalks with their tables. With an emphasis on Spanish-language titles and genre fiction, at first glance the books on offer appear mundane. But if you take the time to really look, something of interest is sometimes dug out of a box.

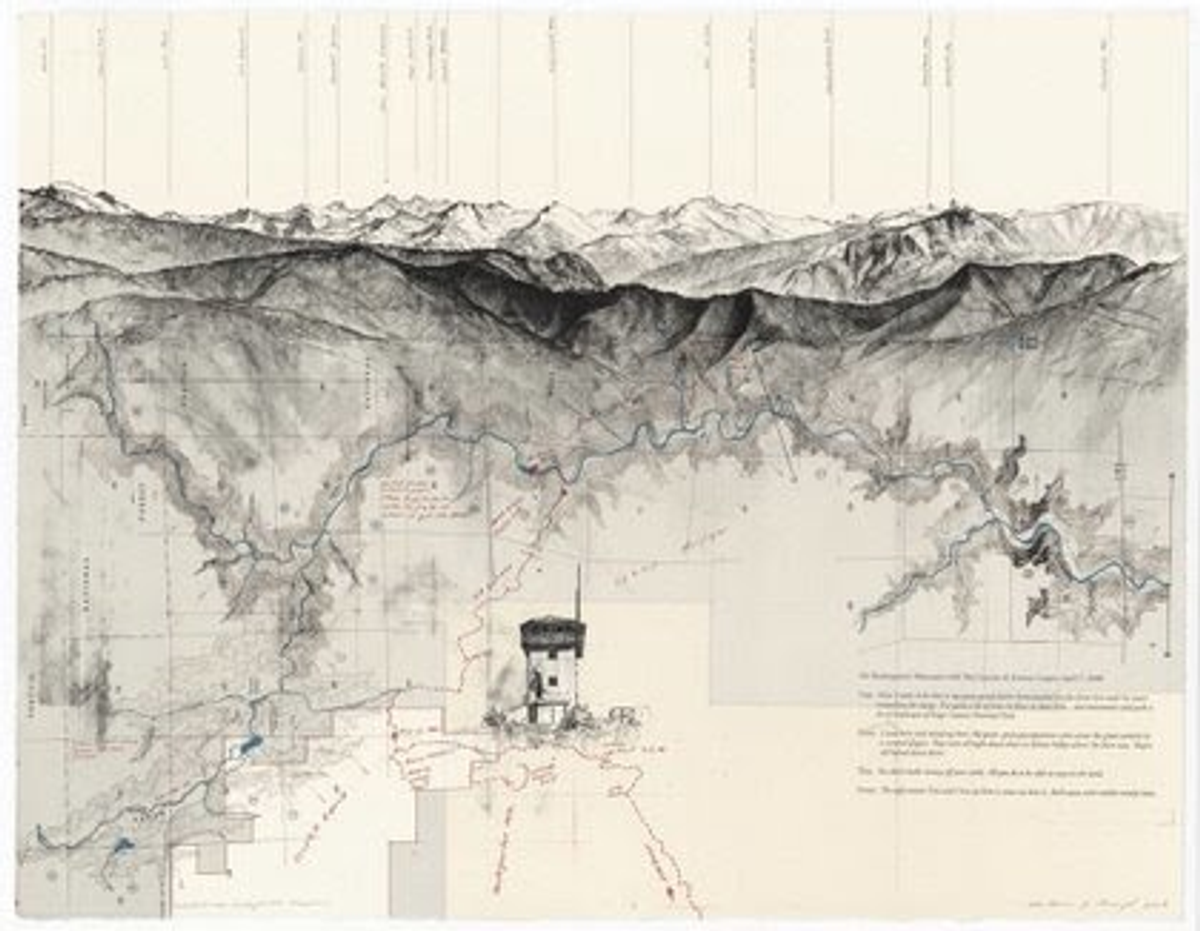

[caption id="" align="alignleft" width="420" caption=""Due East Over Stokes Mountain""] [/caption]

[/caption]

The book, on the whole, is a droll history of maps, from Herodotus’ rendering of the world in 450 BC to topographical maps being able to represent a location’s scenery. Jervis picks apart the development of map making with a dash of subtle Colonial snobbery. In examining the issues involved with determining distance, for example, he cites the “krosh” a unit of measurement in India defined as “two statutory miles, there or thereabouts.” Apparently, “in the jungly parts of Bengal,” branches torn off trees were used to measure a krosh; once the branch wilted, a krosh had been traveled. As Jervis points out, this is a very subjective measurement in which seasonal factors and just how quickly someone walks come into play. He concludes this section by taking a swipe at the idea of a krosh, and India, by writing, “This is also the reason why the most perfect forms of early maps were restricted to areas of higher civilization – Egypt, Babylon, Greece and China.” In this sense, the book serves as an interesting historical document that reflects a broader cultural attitude.

Ultimately, however, Jervis loves maps, as this passage indicates: “Maps are inventions, and like other inventions that have complicated life and made civilization, they have grown and developed. They started, like the motor-car, crude, comic and almost useless. They have developed in two or three thousand years as the motor-car has developed in twenty. Both are now things of beauty, of perfection almost, and of abiding utility.”

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="420" caption=""Due East Over Shadequarter Mountain""] [/caption]

[/caption]

Over the course of leafing through the Jervis books, I also happened to stumble upon the map-based art of Matthew J. Rangel. In “a transect – Due East” Rangel uses the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, rising from California’s San Joaquin Valley, to explore “the ways in which human constructs of land influence our experience of place.” Between 2006 and 2008, Rangel walked a combined 200 miles, documenting the landscapes he encountered by fusing his vision of nature, sublime in the tradition of Romantic landscape painting, with the bureaucratic and commercial boundaries that delineate and define today’s idea of wilderness. Layering his drawings and field notes on top of photographs and government-commissioned maps, the series forces viewers to consider the complex implications of human limits and expectations being imposed on the majesty and uncontrollable force of nature, as seen in jagged mountain peaks and tumbled boulders.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="324" caption=""Due East Through Elliot Ranch""] [/caption]

[/caption]

“The aim of the cartographer is to give a graphic expression to the features of the landscape.” This is Jervis again, but his definition certainly applies to Rangel’s work. You wouldn’t want to use his maps to trek through the Sierras, but in recognizing how our understanding of the natural world is intimately and inextricably linked to the confines of our manmade constructs, Rangel’s work strikes me as true, which might not be as practical as a traditional map, but it certainly might be more useful.

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2011.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America's oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.

Shares