Though I've known Aleksandar Hemon over the years — we first met at the book party for his second work of fiction, "Nowhere Man," at his publisher's house in New York — I've only had a chance to really sit and talk with him in Chicago, my native city and his adopted hometown. I interviewed him in 2009 for Bookforum, about "Love and Obstacles," his last collection of stories, when he told me he hated memoir — which made me laugh, especially since his editor published James Frey, whose loose interpretation of the form landed the "memoirist" in hot water with the formidable Oprah Winfrey. But I remember thinking, as we parted ways, if anyone should be writing memoir, it should be Hemon, a man who has led at least two distinct lives: one in Sarajevo just before the siege, and then his life as an accidental, now naturalized citizen of Chicago, after a junket to the States left him stranded here, unable to return to his war-torn home. And while he has expertly mined this bisected existence for his fiction, I was eager as a reader and as an acquaintance, to learn the "true stories," as they call them in Bosnia (Hemon explains there are no words in Bosnian for "fiction" or "nonfiction," per se).

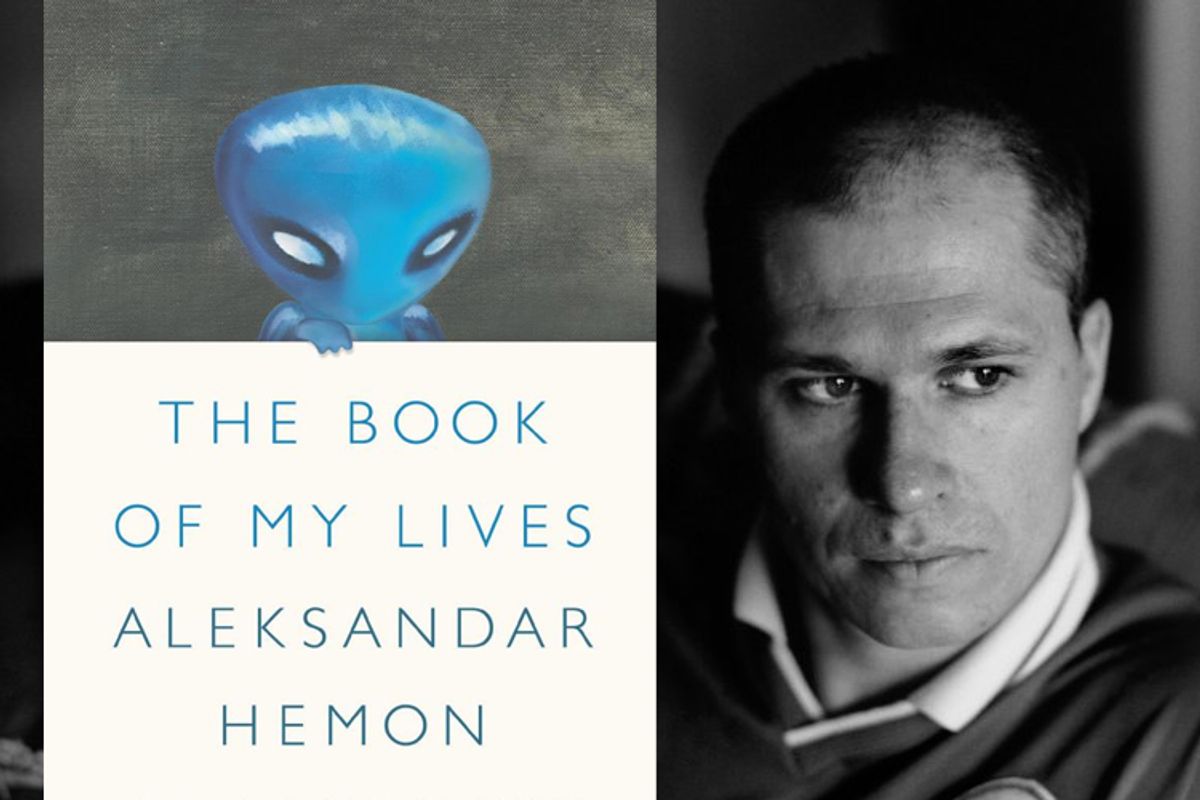

Then his essays started to appear in the New Yorker and Granta and the Guardian, and are collected here, in "The Book of My Lives," which recounts the "stories" before and after the war, in Sarajevo and Chicago, and how the two lives entwined (he has visited Sarajevo many times since his first visit back, in 1997). The tales of his youth, before the war, are darkly funny, as he describes a family trip to Africa that almost didn't come to pass after his father's money belt was stolen; and he is hilariously merciless as he makes fun of his adolescent, snobbish artistic pretensions, recalling his ennui-ridden nihilistic conceptual stunts that got him on the radio, testing his literary mettle by reading short stories and assuming the authoritative voice of a faux historian about a made-up historical figure — and one stunt that caught the attention of State Security, who mistook him for a Nazi sympathizer. And then there are the stories that are more challenging to tell — of the mentor who revealed himself to be a fascist of the worst order, of the hell of bearing witness from afar to an unimaginably brutal war that destroyed everything he ever knew. And, the most devastating and brave of all, his painful recollection of the sudden illness and death of his baby daughter, Isabel, nearly three years ago.

Hemon spoke with me by phone as he was driving the hour-and-a-half trip from Chicago to Milwaukee for a reading on his book tour. We revisited the memoir conversation, and he explained what it is that bothered him about the genre as it has been defined. We also discussed intellectual disillusionment, hedonism as an assertion of agency. And finally, how the vivid imagination and resilience of his oldest daughter, Ella — now 5-1/2, and a storyteller in her own right — inspired him to tell the story of Isabel.

You and I spoke in 2009, when "Love and Other Obstacles" was published, and I remember you told me you hated the genre of memoir.

When I was thinking of the memoir, I had a more narrow definition — the confessional memoir. I could not stand that and I still can’t. I cannot stand that whole game of confession, that is: Here I have sinned, now I’m confessing my sins, and describing my path of sin and then in the act of confession I beg for your forgiveness and redemption. That whole game is played out in public, and sometimes Oprah participates and sometimes not. I really don’t feel that any of the pieces I wrote were confessions; there are no revelations about secrets in my life, and actually I have nothing to confess and I certainly do not ask for redemption and there is no reward for confessing that I expect. The whole James Frey narrative trajectory -- he had to go ask for forgiveness twice, publicly.

I think that sometimes comes from the publisher, too, that desire for an inspirational story arc, where there’s this teachable moment, and an emergence from the morass of sin.

I think that’s the mode of memoir that I think is fundamentally puritan, in the sense that you have to publicly accept your sinfulness and describe your path of sin so as to be forgiven. The whole game annoys the hell out of me. But I grew up reading memoirs of concentration camp survivors and I would have never described them that way. Memoir has turned out to be meaning this mainly confessional memoir, but there’s this whole range of things, there’s an aspect to memoir that’s bearing witness. In Bosnian, there’s no distinction in literature between fiction and nonfiction, there’s no word describing that. I am going to have a hard time defining this book there, because "nonfiction" is not a word, "fiction" is not a word. The closest I can get to it is “true story” and “personal essay.” Memoir over there means a different thing. True stories and personal essays, but I think of them as stories, and some of the pieces were commissioned by editors because I actually told them the story personally, and they said, "Why don’t you write it and we’ll publish it." So in that sense, they were initially told rather than confessed.

There are stories here that are not exactly confessions, but certainly a revelation to readers — wonderfully absurd, like your admission that you, at 5 or so, tried to strangle your baby sister, Kristina, to death.

My sister and my parents have known for many years [laughs]. They were not shocked to find out.

That was a classic sibling Freudian moment.

I remember she started vomiting and my mother remembers that she started vomiting, so I remember that I effected that. Could be residual guilt or jealousy. I owned up to it right away.

And then, much later, when you were late teens and ennui-ridden nihilists, at your friend Isidora’s birthday party — she opted for a decadent Nazi theme, a prank that got out of hand because the party was mistaken for a Nazi meeting, which caught the attention of the government. That must have been terrifying.

It was terrifying.

Later you talk about the professor who was once a mentor, Professor Kojevic, until you discovered he'd become Radovan Karadzic’s right-hand man. You described needing to unlearn everything he taught you, because his evil had far more influence on you than his literary vision. Do you really believe that?

I do, I do, I do. Because I liked him when he was a college professor, and I had to work against what I thought about literature before the war, before he came out as a fascist, and had to seriously rethink the whole thing. I had another professor who I hated from the first day who also joined the Serbian fascists, and he was said to have kicked a human head like a soccer ball, but I had no trouble dismissing everything that he taught me as he was teaching me. I was caught up in my professor, Kojevic, and his approach to literature made sense to me and I built a whole aesthetic based on that, as it were, and this is what I had to take down and see what’s left of it. And so this requires a lot of reading and rereading and which also coincided with my need to acquire English so I could write in English by reading. It was a twofold project, as it were, in the early '90s. I also had to think, and almost every one of my friends was thinking, should I have known? When I was in college, did he show his fascist proclivities? Was I not paying attention?

Those proclivities may not have been fully realized at that point.

What I concluded in the end, is that, in thinking that I may have had a chance to notice such proclivities, it sort of assumes psychological and therefore moral and ethical continuity. And it’s not exactly how it works, because the rupture of something like war, it activates dormant potential in them so without war, he might not have been a fascist. Or he might have just been a Republican [laughs]. But the war offered an opportunity for people like that to pursue their worst potentiality, he actualized the worst parts of himself, and after the war, some people turned to being good neighbors. But you cannot undo what’s done by reverting back to be a decent human being because what’s done cannot be undone.

You describe this hedonistic, hysterical oblivion just before the war breaks out, a euphoric determination to seize life, party, drink and dance in the face of destruction, like it's a big "fuck you" to war.

There were people on the siege — obviously I was not there — but they continued some of those things, the means of resistance, including watching movies. It was important to continue some form of social life or celebration of life, even if it was euphoric, as a means of resistance. I remember a friend telling me they would party, there was a club at the Academy for Dramatic Arts, and people would play music really loud, whatever was cool at the time, the new Nick Cave album or Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, and they would crank it up and turn the speakers toward the mountains where the Serbs and snipers were and say, "Fuck you, listen to this music!" Obviously it didn’t stop anything but they were somehow seen as resistant. If you could dance or see a movie under those circumstances, you still had agency. A friend of mine told me a story, she was a doctor and operated daily on wounded people and shot people and people died in her hands, but she ran under sniper fire in 1993 or '94 to see “Terminator 2.” She was willing to risk her life for “Termination 2” and I can’t imagine “Terminator 2” provides such rewards that it’s worth risking your life. But it was the act of going to see a movie that was really worth risking your life because without that, what is life?

Your parents had a country getaway 20 miles outside of Sarajevo that you describe in the essay "The Magic Mountain," where you sought solace and cleared your head and read for hours at a time. Have you found something like that here?

No, alas, no. Only when I fly across the ocean, six hours at a stretch, so I can read a book on a flight. I just read the biography of Iggy Pop on my flight [laughs], speaking of that euphoria. So no, I don’t have a treat like that at all. I long for, not a writer's retreat — I can write in any situation — but a readers’ retreat.

Music plays a strong role in your work — you have an essay here named for David Bowie's "Sound and Vision," for example — and punk and new wave; it is almost as integral to your aesthetic as the books you were reading. How old were you when you discovered American and English punk and new wave in Sarajevo?

There was a moment when I converted to punk and new wave; I talked a friend in elementary school into buying a record. He was going to buy “Dark Side of the Moon,” Pink Floyd. And I somehow talked him into buying the Clash’s first album, and he hated it. He only liked one song [laughs]. And I exchanged a Led Zeppelin album for an XTC album and I never looked back. Though I do have some Led Zeppelin now. I was 11 or 12. I was in elementary school.

Have you gotten David Bowie’s new album?

Yes.

So, what do you think?

I like it. I’ve listened to a few songs, I like that I have to listen to them thoroughly. Because I was reading the Iggy Pop biography, and then I went back to the Iggy Pop and Bowie albums that they recorded in Berlin in the '70s. But reading about it made me want to listen to them again in detail and pay attention. And then I listened to the new Bowie album, and that’s nice. I’ll pay more attention to it once I get over the relistening of these old things, “Lust for Life” and “Heroes.”

Do you still feel like your life is bisected?

I have managed to convert Chicago into an adopted hometown for myself. I love it here. I have the network. I still have a strong connection to Sarajevo. My parents have an apartment there and go every year from Canada. My sister who lives in London, she comes down with them. And I usually go too. I feel a connection with Sarajevo as it is right now, however uncomfortable and complicated. It is not just revisiting my youth; I’m visiting many people I know and like and some people I work with, so it’s a full long connection.

When was the last time you were there?

Spring of 2011. But before that, I’d gone two or three times a year, since 1997. I wrote almost half of my novel "The Lazarus Project" there; I was there for six weeks, in 2005. When I go there, I have people to play soccer with. I easily fit into the life. There’s some catching up with people that I haven’t seen, but it isn’t 10 or 15 or even two years of catching up, it’s the past few months of catching up. So I feel like I have layers, and a lot of it is Sarajevo and a lot of it is Chicago. Not to mention that there are a lot of Bosnians in Chicago, a lot of people from Sarajevo.

Someone on Facebook, a Chicagoan in the literary community, said today, "You know you’re a Chicagoan if you refer to Aleksandar Hemon as 'Sasha.'"

[Laughs] My wife and I maintain this list, and we have a party once a month that we call Chicago Literary Salon, people who are in any way connected to writing and literature in Chicago and then some others who are friends, artists or photographers, they come by. We made quite a lot of new friends doing this because they brought friends.

So this is a tough question and I'm not even sure I know how to approach this without sounding grating, so I'll keep it simple: How did you know when it was time to write about losing your baby daughter, Isabel?

I don’t remember exactly. I was telling someone about Ella [his older daughter, now 5-1/2 years old], and essentially I wanted to write about Ella, but I could not set it up without Isabel’s illness and death. At which point I was talking to the New Yorker editor and I asked her if she wanted to see that if I wrote it. The New Yorker editor, she’s a friend of mine and she’s very sensitive and delicate about it and so I decided to try to write it, and then I wrote it. Long story short, I could not not write it. I realized that I had to write it because it would have meant that I can’t confront this thing, which would have been the first step on the way to erase and diminish the memory of Isabel and everything that she was and is for us. I have been confronting and dealing with it and Ella was the inspiration,; she provided a way to understand so I decided to write it.

How did your wife feel about you writing about it?

We discussed it. The other thing with memoir, a large part of that book is about other people, and other people are more than relevant to my life, they constitute me. She conceives of privacy differently and so she would not have written it, but she told me that if I had to do it, I should do it. She obviously read a draft or two and the final version that was published in the New Yorker. I have to say that, when we were in New York (teaching), Ella went to this school in Chelsea and they had to describe and draw their family, and Esther, my youngest, was born. And Ella drew five of them. Between Esther and Ella, there’s Isabel. Of course, Ella knows that Isabel is dead, but her life and death has been integrated into Ella’s life and our life too, and so it didn’t happen because I wrote a piece, but writing a piece was part of that integration, so that we could not avoid talking about it or thinking about it. There are pictures of Isabel all over our house, we talk about her, Ella talks about her, she knows what happened. It’s not something I wanted to cover up because it was too difficult to deal with. Writing it doesn’t make it easy to deal with, but at least I’m dealing with it and continue to deal with. But I miss my child every day and I don’t look for ways to tranquilize myself.

Shares