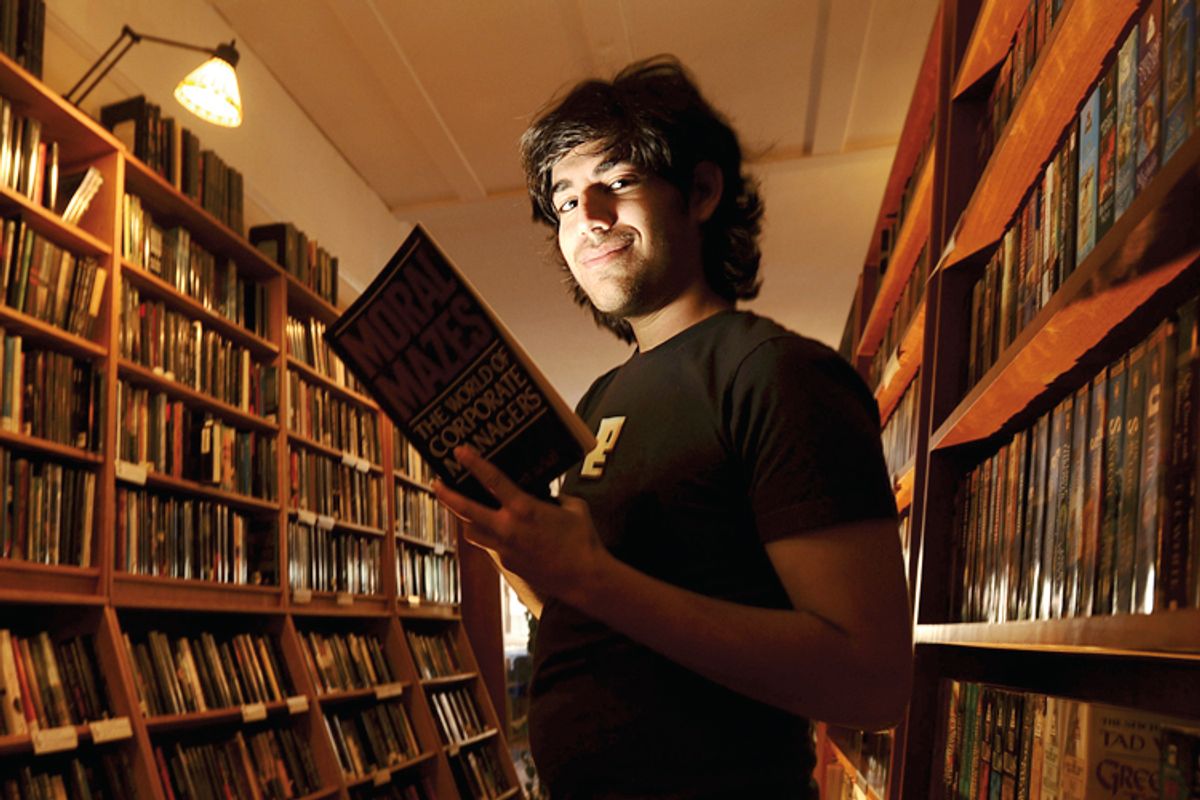

Friends and defenders of Internet activist Aaron Swartz are angrily denouncing the report released Tuesday investigating MIT's role in his prosecution (and, implicitly, responsibility for his suicide). Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, Swartz's partner at the time of his death, immediately released a harsh statement: "MIT’s behavior throughout the case was reprehensible, and this report is quite frankly a whitewash."

The reaction is understandable. At first glance, no one who supported Aaron Swartz could be expected to be happy with a report that MIT's own president, L. Rafael Reif, summarized as supporting his belief that "MIT's decisions were reasonable, appropriate and made in good faith."

But after reading the full report, I'm not so sure that President Reif is fairly characterizing the thrust of its analysis. On purely technical issues, the report gives MIT a passing grade, while explaining the sequence of events that pushed MIT to adopt a position of "neutrality" on whether Swartz should be prosecuted. MIT didn't actively seek Swartz's prosecution, but it also didn't make any public comments criticizing or opposing it. (This was in sharp contrast to JSTOR, the online archive that could actually make a case for being harmed by Swartz's actions. After JSTOR reached a settlement with Swartz, the federal prosecutor's office was told that the archive opposed further criminal prosecution.)

Swartz advocates looking for an explicit challenge to the neutrality position will be disappointed. But on the question of whether MIT's actions lived up to its own culture and important position in the world of computer technology, the report is actually quite critical.

Let's start with the concluding paragraphs:

In closing, our review can suggest this lesson: MIT is respected for world-class work in information technology, for promoting open access to online information, and for dealing wisely with the risks of computer abuse. The world looks to MIT to be at the forefront of these areas. Looking back on the Aaron Swartz case, the world didn’t see leadership. As one person involved in the decisions put it: “MIT didn’t do anything wrong; but we didn’t do ourselves proud.”

It has not been the Panel’s charge for this review to make judgments, rather only to learn and help others learn. In doing so, let us all recognize that, by responding as we did, MIT missed an opportunity to demonstrate the leadership that we pride ourselves on. Not meeting, accepting, and embracing the responsibility of leadership can bring disappointment. In the world at large, disappointment can easily progress to disillusionment and even outrage, as the Aaron Swartz tragedy has demonstrated with terrible clarity.

Reasonable? Appropriate? Good faith? Do President Reif's characterizations jibe in any substantive way with the shame that leaks through every sentence in those two paragraphs?

Now let's back up from the conclusion. In a section devoted to questions that the MIT community should be mulling over in the aftermath of Swartz's suicide, the authors of the report include a damning summation of what MIT has historically stood for.

MIT celebrates hacker culture. Our admissions tours and first-year orientation salute a culture of creative disobedience where students are encouraged to explore secret corners of the campus, commit good-spirited acts of vandalism within informal but broadly -- although not fully -- understood rules, and resist restrictions that seem arbitrary or capricious. We attract students who are driven not just to be creative, but also to explore in ways that test boundaries and challenge positions of power.

In the context of MIT's decision to maintain a position of "neutrality" on the question of whether or not the U.S. government should prosecute Aaron Swartz, the "hacker culture" quote can be read as nothing other than condemnation of MITs' actions. JSTOR could make a reasonable case that its access rules were broken and its operations imperiled by Swartz's activities. But MIT, an institution that prides itself on allowing open access to its networks, refused to take a stand.

"MIT’s position may have been prudent," says the report, "but it did not duly take into account the wider background of information policy against which the prosecution played out and in which MIT people have traditionally been passionate leaders."

If the Review Panel is forced to highlight just one issue for reflection, we would choose to look to the MIT administration’s maintenance of a “neutral” hands-off attitude that regarded the prosecution as a legal dispute to which it was not a party. This attitude was complemented by the MIT community’s apparent lack of attention to the ruinous collision of hacker ethics, open-source ideals, questionable laws, and aggressive prosecutions that was playing out in its midst. As a case study, this is a textbook example of the very controversies where the world seeks MIT’s insight and leadership.

I can't read the report any other way: MIT's decision to be "neutral" betrayed what many people believe MIT as an institution should stand for. It was an abdication of leadership.

Shares