Philip K. Dick saw the future. At least, he saw the future of high-concept Hollywood sci-fi. Many of Dick's novels and stories have been adapted into films, like "Blade Runner," "Total Recall" and "The Adjustment Bureau." But his influence is much broader than that, as his characteristic concerns (what is reality? what does it mean to be human?) and his pomo, busted puzzle-box approach have served as the basic blueprint for everything from the super-successful "Matrix" series to the instantly and justly forgotten "Source Code."

Spike Jonze's "Her" is the latest variation on the Philip K. Dick theme. In particular, it evokes Dick's classic 1968 "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?," a book very loosely adapted for the film "Blade Runner." Like "Androids," "Her" is built around the question of whether androids, or AI, can be human, and whether, in particular, they can feel empathy.

It's easy, in fact, to see "Her" as an almost direct response to "Androids." That book, like all of Dick's novels, is suffused with anxiety, in this case linked to paranoid technophobia. The main character, Rick Deckard, is a bounty hunter charged with "retiring" (that is, killing) a new kind of smarter android, which is almost indistinguishable from humans. The one difference between humans and androids is empathy; androids don't have it. Perhaps the most horrifying passage in the book involves an android, Pris, carefully pulling the legs off a spider to see if it can still walk.

"With the scissors Pris snipped off another of the spider's legs. 'Four now,' she said. She nudged the spider. 'He won't go. But he can.'"

The scene (not reproduced in "Blade Runner") has the quiet, bleak force of nightmare. It's an uncanny-valley vision of a thing that looks human, and acts human, but isn't quite — of a techno-future in which, by implication, humanity itself becomes a remorseless, uncaring machine.

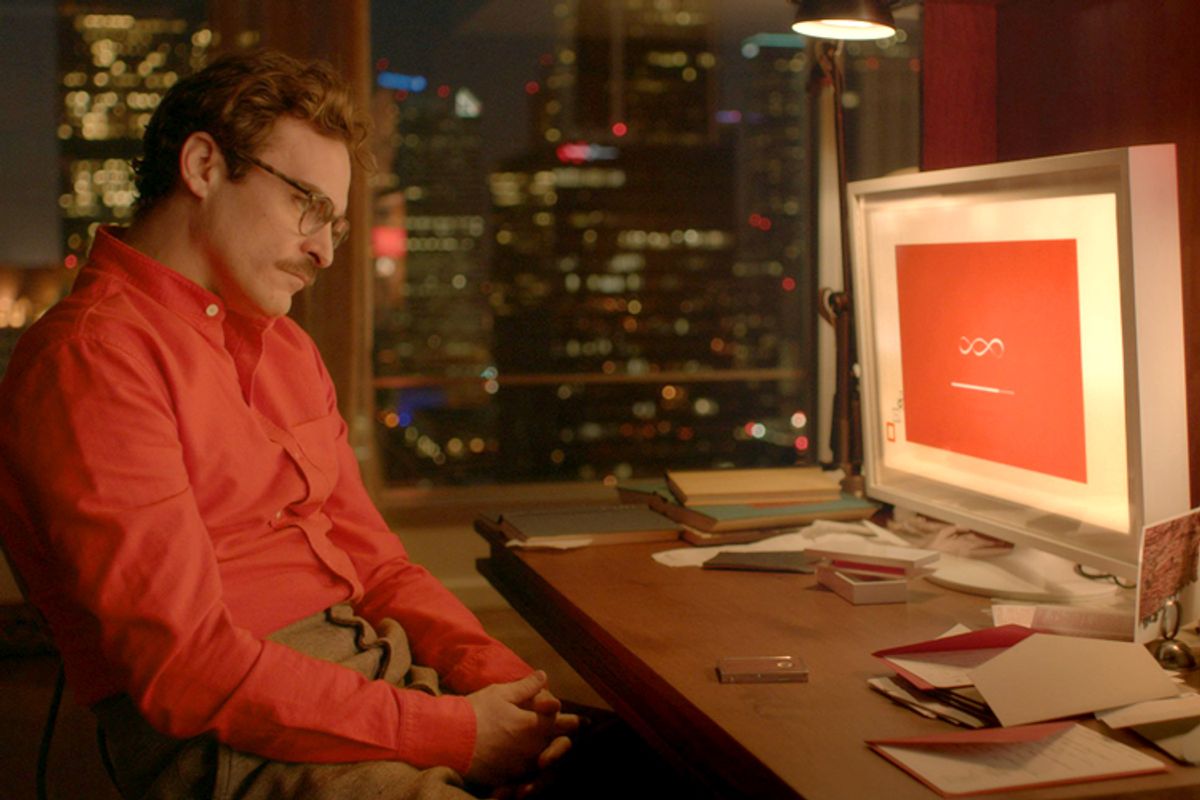

Forty-five years after "Androids" was published, "Her" is here to tell us that those worries were way, way overblown. Jonze's future is not a hell; on the contrary, it extrapolates our present omni-wired society into a kind of techno-utopia, where mediated digital connection expands upon and enables ever more empathic humanness. The main character, Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), works at a dot-com composing meaningful, beautiful letters for others on commission, encapsulating the essential feelings of a relationship for those too tongue-tied to do it themselves. Even more to the point, Theodore falls in love with an AI operating system named Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson), who is characterized specifically by her intuition and consequent talent for emotional intimacy. Technology is not dehumanizing, but rather ultra-humanizing.

This humanization, or extension of empathy, isn't just about accepting robots as human; it's about accepting, and embracing, all kinds of difference. As such, it can be seen as demonstrating, and celebrating, the social progress made since Dick's downbeat novel. In "Androids," the human-like robots are figured in part as marginalized minorities, marked as different, the better to despise them, loathe them and hunt them down with the sanction of the government and, to a large extent, of the novel itself. The fear and hatred of the other is mixed up, too, with Dick's complicated, but definite, misogyny. Rachael Rosen, an android, sleeps with Deckard to manipulate him, her calculation and emotional remoteness fitting neatly into noir cold bitch stereotypes. Seeing androids as truly different and inhuman, then, becomes a way for the novel to process difference — whether of race, class or gender — as evil or dangerous.

In "Her," on the other hand, Samantha is accepted not just by Theodore, but by nearly all his friends and family. Dating an operating system is normal and accepted — the link to gay rights is surely intentional. Those who insist on seeing Theodore and Samantha's relationship as aberrant or lesser — as do both Theodore's estranged wife and to some extent Theodore himself — are presented as clearly in the wrong. Nor is Samantha an occasion for misogyny; rather, she's the voice of the film's enthusiastic pro-feminine vision. Emotion, empathy, sentiment — all are associated with Samantha's female voice, and enthusiastically embraced. When one of his co-workers tells Theodore he's part woman, it is meant, by the co-worker and by the film, as a good thing.

As a compliment to women, though, Theodore's femaleness is double-edged, since it serves, in large part, to eclipse any actual women in the story. The relationship with Samantha is presented, rhetorically and insistently, as a full-fledged romance between equals. But the fact remains that we never see Samantha, and only hear her voice when she's talking to Theodore. The initial image of the film — an extreme close-up of Theodore's head — is indicative; he takes up all the space. It's true that Samantha does have an arc of growth and change, but that arc is all processed through and observed from Theodore's perspective, and so is almost entirely experienced as part of his story, his healing and his growth experience. The movie tells us that Samantha is a person, but it treats her as little more than an app for overcoming Theodore's midlife crisis — a way to move him from his wife to, at the end of the film, another conventional relationship with a woman we hardly know because, hey, who cares, she's a woman, right? The assertion that difference doesn't matter becomes a means, or an excuse, to erase difference altogether. Samantha is gone; Theodore remains, homogenous and unitary, the only story that ever mattered in the first place.

In "Androids," on the other hand, the anxiety about difference opens up a space in which difference can be seen as, actually, different. This is certainly true for class issues. In "Androids," money and social status are a constant, nagging worry for everybody, while in "Her," Theodore's job as mid-level cubicle slogger somehow pays for a spacious apartment, unlimited techno-toys and lavish vacations — middle-class existence appears to be as much a universal default as Theodore's own gigantic head.

In addition, though Deckard is the main character in "Androids," we also spend a good bit of time in the consciousness of J.R. Isidore, a truck driver for an artificial animal repair shop who has been classified as a "special" because of his low IQ. Isidore's marginal status is linked repeatedly to that of the androids; he lives in the same abandoned building they do, and he's treated as different and lesser, as they are. He's set apart from them by his ability to empathize — but that ability is in no small part an ability to empathize with them. By the same token, another bounty hunter, Phil Resch, is marked as an android because he doesn't empathize with other androids — and then revealed to actually be a human who doesn't empathize with androids. Deckard's humanity too is occasionally questioned, both because various people wonder whether he's an android, and because he turns out to be able to kill an android that looks exactly like Rachael, the android he slept with.

In "Her," difference is simply subsumed into a single narrative of midlife crisis and romance — everybody's the same at heart, which means everybody is accepted as long as their stories can be all about that white male middle-age middle-class guy we're always hearing stories about. In "Androids," on the other hand, different people, and different machines, are actually different. That's frightening in many ways — both because difference itself can be frightening, and because difference seems to excuse and even encourage violence and alienness in "us," whether we empathize (like Isidore) or joyfully murder (like Resch).

Which is to say, Dick is willing to see empathy not just as a way to treat the other as the self, but as a way to view the self from the perspective of the other as android, alien, inhuman. Thus the middle-class dude doing his job can be seen, not as a dispenser of greeting-card good cheer, but as a murdering borderline psychopath. Looking forward from Dick's past, Theodore's soulfully empathic gaze starts to look less like a comforting promise, and more like a threat — a future in which we are all accepted because we are all buried in that one guy's mildly quirky, eminently predictable dream.

Shares