In a surprise move without precedent in the history of college sports, Northwestern University football players have petitioned to form a labor union.

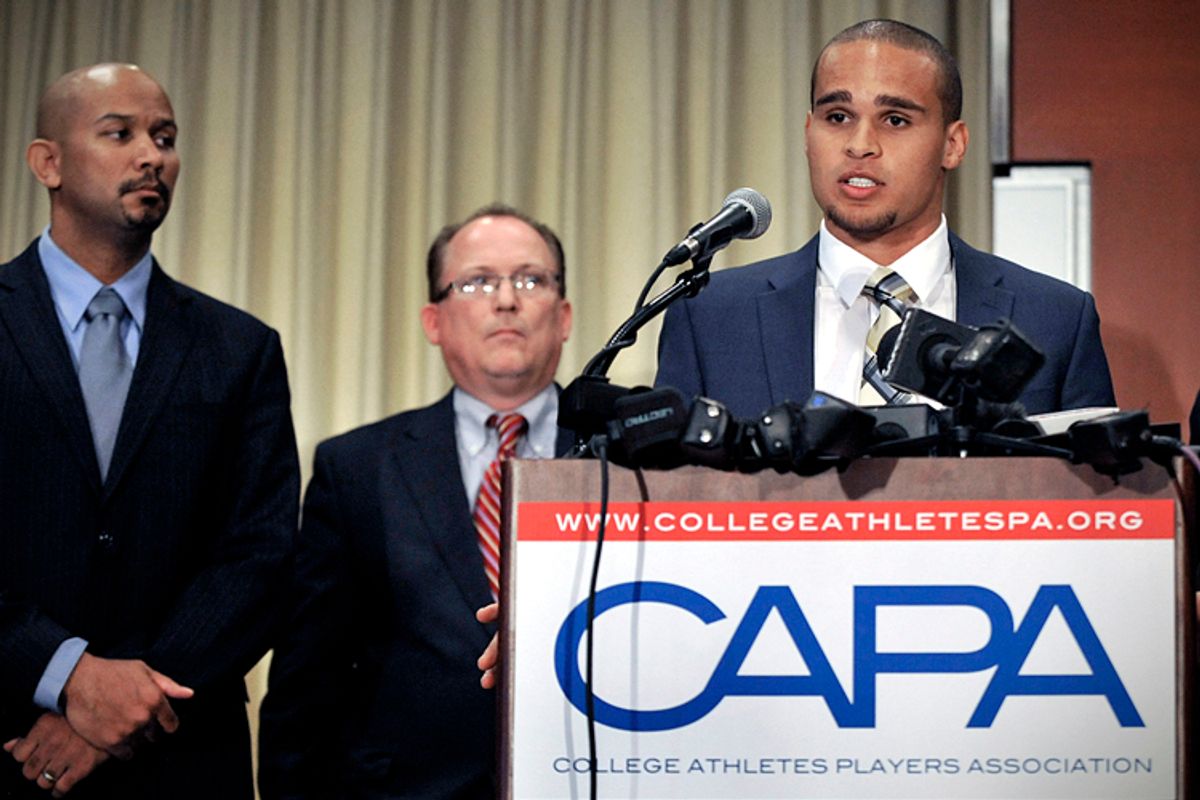

“Something we talked to the players about – we said, look, we don’t know what the timeline is, there could be a number of appeals, and many of you could be gone,” said Ramogi Huma, a founder of the new College Athletes Players Association. “It’s possible that many of you will never directly benefit. But we said … if you believe it’s the right thing to do, then it’s a chance that no other college athlete’s had, to stand up in this area for not only future players at Northwestern, but future players across the nation.”

“And the response,” said Huma, “was just overwhelming.”

Huma filed the petition Tuesday with the National Labor Relations Board, the federal agency responsible for enforcing and interpreting most private sector labor law. Huma also directs the National College Players Association, a non-union group that, as I’ve previously reported, has mounted increasingly aggressive challenges to the NCAA since Huma, an ex-UCLA linebacker, founded the group in 2001.

An NLRB spokesperson told Salon the agency will hold a hearing on the petition Feb. 7. That could be the first step in a multi-year, precedent-setting legal battle, as both Northwestern and the NCAA insist the athletes aren’t employees covered by the New Deal National Labor Relations Act. “I think it is likely that they will prevail,” said former NLRB chairman William Gould. But “the matter could take two to three years at a minimum,” given the “long and convoluted process that is embedded in American labor law, that the university will take full advantage of.”

In an emailed statement, Northwestern vice president of athletics and recreation Jim Phillips said the students’ NLRB petition was in line with the school’s urging that they “be leaders and independent thinkers who will make a positive impact,” and that the “health and academic issues” they’d identified “deserve further consideration” – but that the school “believes that our student-athletes are not employees and collective bargaining is therefore not the appropriate method to address these concerns.”

An NCAA spokesperson referred Salon to a statement from the league’s chief legal officer, Donald Remy, which offered a similar upshot to Northwestern’s, though a less conciliatory tone. “This union-backed attempt to turn student-athletes into employees undermines the purpose of college: an education,” warned Remy. He added, “Student-athletes are not employees, and their participation in college sports is voluntary. We stand for all college athletes, not just those the unions want to professionalize.”

Huma dismissed that response as “more hypocrisy,” saying the athletes “are paid in the form of scholarships, on the condition that they provide a service and continue playing football or basketball. If they don’t show up to play in the games, that payment goes away.” Further, he told Salon, “I don’t think you can name another employee that the university has more control over than its football and basketball players.” NCPA notes over a billion dollars in additional revenue coming to the NCAA from its most recently negotiated contracts; scholars note that the sport’s influence over players’ lives extends to what they consume year-round and how they spend their vacation time.

In interviews with Salon last year, former UCLA power forward James Keefe recalled players “busting their butt four hours a day, five hours a day” even during the off-season; former University of Kentucky cornerback Anthony Mosely described anxiously awaiting a financial aid check that determines “whether you can pay rent” – while the university profited off of selling apparel with his jersey number. “I don’t see how you can really describe it as anything but a job being an athlete,” said UCLA punter Jeff Locke.

The unionization push (not formally directed by NCPA) opens a new phase in the college athletes’ efforts, which have previously included petitions, reports and an act of on-the-field collective action: players affixing the letters “APU” – for “All Players United” to their uniforms during nationally televised games last fall. As recently as last year, Huma told Salon that if a group of athletes sought support for a union drive, he would need to bring the question to NCPA’s board.

What changed? “We’ve appealed to lawmakers, and we got a few laws passed; you know, we’ve talked to Congress, we’ve helped on lawsuits, we’ve put together intense public pressure campaigns,” Huma told Salon Wednesday. “But it’s clear, you know, in a multibillion-dollar sports business, for players to have protections, that the answer is to form a labor organization so that the player can collectively bargain for things on a comprehensive level.”

Huma said it was after personally reaching that conclusion that he got a phone call from Kain Colter, a Northwestern quarterback who participated in September’s “APU” action. Huma said Colter told him “we need a players association just like the pros,” and “he was confident that his teammates felt the same way. And after meeting with him over the weekend, King was obviously right.”

“Right now the NCAA is like a dictatorship,” Colter told ESPN. “No one represents us in negotiations. The only way things are going to change is if players have a union.”

The new CAPA union effort is backed by the United Steelworkers, which has supported NCPA for over a decade. Huma said CAPA had not formally affiliated with the USW, and that any decision about whether to do so would be made by members after securing legal victory. The union effort was also hailed by the nation’s main union federation: In an emailed statement, AFL-CIO president Richard Trumka said, “Under the system that the NCAA and its member institutions like Northwestern have established, college football and basketball are big business and treat athletes that way.”

As I’ve reported, both the AFL-CIO and the USW have taken on an increasing role in backing “alt-labor” groups like the NCPA, which have sought to raise standards without collective bargaining. Some of those groups, like OUR Walmart or the AFL-CIO’s non-union affiliate Working America, remain focused on legal, political, media, consumer or industrial activism tactics to secure changes without bargaining; other efforts, like the Milwaukee immigrant/ workers’ group Voces de la Frontera – and now the college athletes’ – have laid the groundwork for NLRB unionization efforts. Like port truck drivers or home care workers, whether given groups of college athletes have the legal right to secure collective bargaining is subject to debate.

And it could vary by state. While the NLRB covers private sector companies, like Northwestern, across the country, most NCAA teams are at public universities, where any unionization bid would be governed by state-by-state public sector labor laws. That means collective bargaining rights are entirely off-limits in some states, but could be easier to achieve for public university players in more pro-union states than for their private sector counterparts at Northwestern. Thomas Frampton, the co-author of a Buffalo Law Review essay on the topic, last year told Salon that in at least 14 states, if officials “were to follow their own law” and precedent, “the case is incredibly compelling, and in some states overwhelming.”

The NCAA and the CAPA each expressed confidence their side would ultimately be vindicated in the Northwestern legal battle. Gould, now a professor at Stanford, predicted that the case would ultimately be appealed from the NLRB into federal court. Asked whether collective bargaining at Northwestern alone would be feasible, Huma said, “potentially,” but that the goal would be to organize college athletes across the country, at which point “various options” would present themselves, including a nationwide agreement. If Northwestern athletes establish a precedent that they have the right to organize, Huma told Salon, “That would be a big domino to fall.”

College athletes, argued Huma, are “the most visible marketing arm of the institution, and the institution has to respect that.” The Northwestern football team, he suggested, is no mere outlier: “Players across the nation feel the same way … They’ve never felt like they had a voice, and they’ve never had a seat at the table.” Added Huma, “We know the people that these players have. It’s really never been channeled this way.”

Shares