This week, former Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice appealed his indefinite suspension from the NFL. We all know what preceded the NFL's latest move on the matter. Earlier this year, Rice assaulted his partner in an Atlantic City casino elevator, ultimately knocking her unconscious. After the assault, the NFL had in its hands a confession from Rice, a detailed and damning police report, a grand jury's indictment and security footage showing Rice dragging Janay Rice's limp body into a hallway. In response to the evidence presented, the NFL benched Rice for two games and deployed its media team to spread the word about what a good man he really was. But the NFL changed its tune after video of Rice striking Janay was released, not because the details changed, but because the optics did.

The NFL's cynical, inept and increasingly flailing responses to Rice -- and to other domestic violence cases within the league, like those of Carolina Panthers defensive end Greg Hardy (convicted on domestic violence charges) and Minnesota Vikings running back Adrian Peterson (facing child abuse charges in Texas) -- have made the public pretty angry. Which has made advertisers nervous. Which has moved a string of corporations to condemn, however weakly, the NFL's handling of domestic violence among its employees. Which has had the weird effect of turning massive and terrible corporations into de facto arbiters of morality and agents for social change, at least when it comes to the NFL.

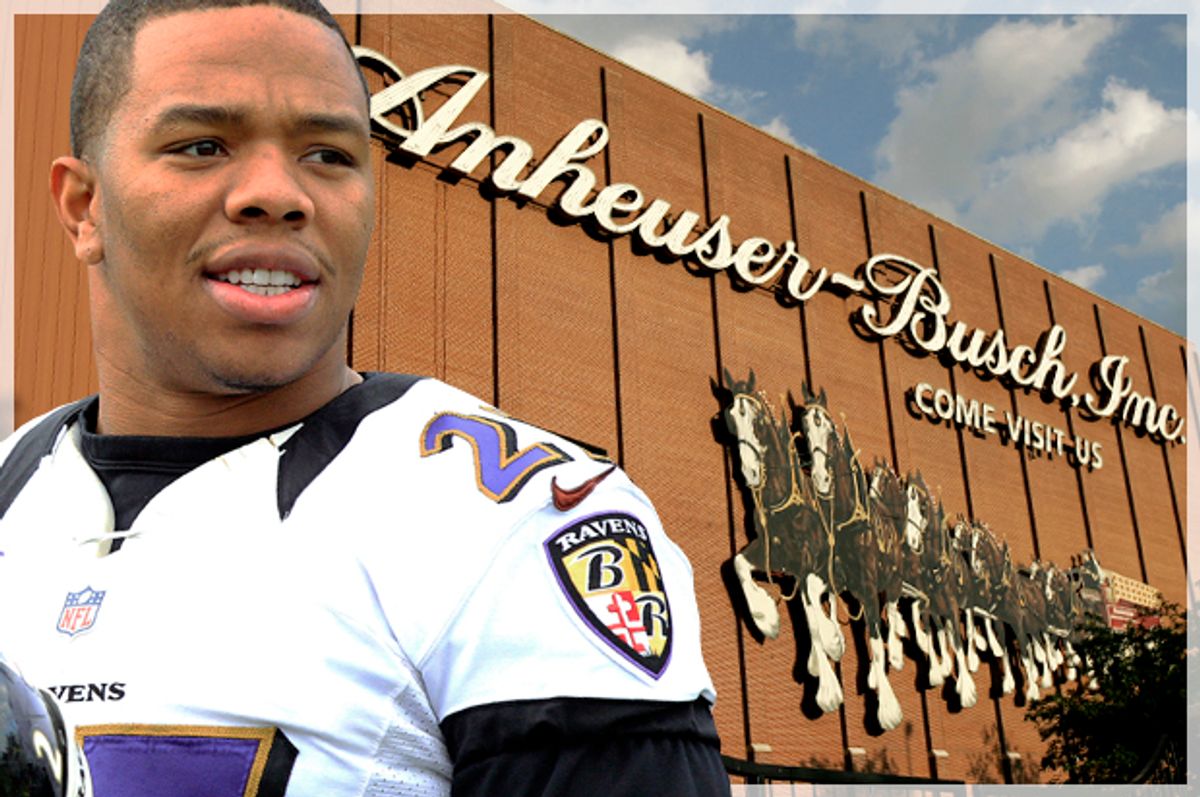

If public outrage hasn't been enough to unseat Goodell and implement systemic changes within the NFL's highest ranks, a serious economic hit -- in the form of massive sponsor defections -- might be the thing to force the change. Does that make, say, a beer company an uneasy but strategic ally in the movement to make violence unacceptable? Or, more to the point, to make the appearance of indifference to violence immensely unprofitable? And what does all of this say about us as a culture, when, as one of my colleagues put it, our new standard of "morality" is dictated by the point at which corporations become too embarrassed to advertise?

There are certainly some strange alliances and fractures forming in the wake of the NFL's continued indifference to its domestic violence problem. Last week, senior digital editor for the American Prospect Adele Stan started a meme calling on CoverGirl, the “official beauty sponsor of the NFL,” to break its financial ties. The company's response to the viral campaign was tepid. “We developed our NFL program to celebrate the more than 80 million female football fans,” CoverGirl said in a statement. “In light of recent events, we have encouraged the NFL to take swift action on their path forward to address the issue of domestic violence.”

CoverGirl's lukewarm response came as a disappointment to activists who thought its bottom line -- women's dollars -- would force the company to act. And as Scott Soshnick pointed out at Bloomberg on Wednesday, women-led corporations like General Motors, Pepsi Co. and Campbell Soup Co. have been pretty silent on the matter.

But this week, Nike dropped its contract with Peterson in the wake of the child abuse charges. (I will leave you to sort out Nike taking a stand against child abuse, given its labor history.) And the comparatively strongest statement on Peterson and Rice, at least among other major NFL sponsors, seems to have come from a beer company. In the light of the Rice case and the Vikings' deactivation (and reinstatement and deactivation) of Peterson, Anheuser-Busch issued a statement expressing its apparent concern. "We are disappointed and increasingly concerned by the recent incidents that have overshadowed this NFL season," a corporate representative said in a statement. "We are not yet satisfied with the league's handling of behaviors that so clearly go against our own company culture and moral code. We have shared our concerns and expectations with the league."

While months of sustained outrage from activists and fans were largely ignored by the NFL, the beverage giant's concerns were addressed immediately. "We understand. We are taking action and there will be much more to come," said NFL spokesman Brian McCarthy.

This is a familiar pattern. The money says jump, and the response is, "How high?" But while the corporate actions that have been taken are no doubt driven by the same cynical forces that drove the NFL to drop Rice and temporarily bench Hardy and Peterson -- namely, egregiously bad publicity -- they may be able to level the kind of blunt impact that will make the NFL, say, force Goodell to resign. Or Harbaugh, or Vikings owner Zygi Wilf or [insert gross millionaire here]. Which makes them kind of useful in this whole matter of bringing the NFL to account, even while the companies themselves remain terrible.

It's long been clear that the NFL is (to quote writer Jessica Luther's astute phrasing) a "soulless behemoth of a money-making machine," but it's also possible that other soulless behemoths of money-making machines, if public pressure remains strong and direct about its objectives, could be the thing to bring it down.

Steve Almond, who wrote "Against Football," believes the NFL will only change if fans turn away. He makes a persuasive point. "The NFL is a huge and hugely profitable corporation," he told me last month. "Regardless of what we're talking about, violence against women, attitudes about drugs, their extortion of cities -- that's all power that we gave them. Don't like it? Then turn away from it. Don't give it your money."

But the corporate shaming of another corporation may be the closest we'll come to change, short of fully opting out. If pressure from the public keeps this ugly enough that advertisers go further than issuing statements of disappointment and actually turn away, we might just see the kinds of structural reforms that offer some measure of reform at the NFL. (Like, say, bringing more women into leadership positions. Since the NFL's diversity report was dismal again this year on the issue of gender.) But that won't happen unless consumers force the issue, and it seems like now is the time to do it. Until then, the NFL will be content to remove players to appease a public hungry for accountability while the rot in their C-suites continues to fester.

It's fighting big money with big money. It's an uncomfortable fight, to put corporations that routinely act against the public interest in the role, however superficially, of social justice actors. And it's a limited fight, since the sins of the NFL extend far beyond what we're seeing play out right now. But, however flawed, it seems like the fight we have before us.

Shares