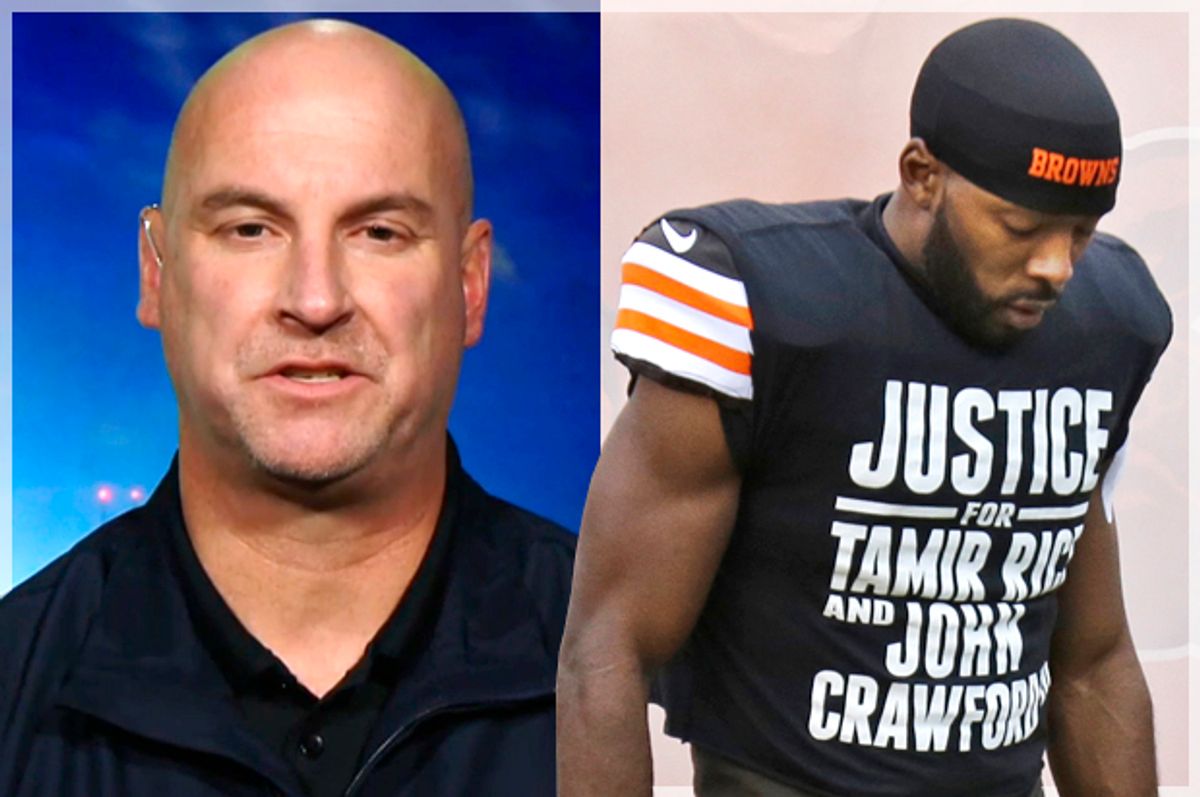

“We’re not apologizing to anybody.” This is how Cleveland police union chief Jeffrey Follmer answered a question about whether the city’s police department regrets demanding an apology over Andrew Hawkins of the Cleveland Browns’ on-field protest, but he might as well have been talking about Tamir Rice’s parents. Or John Crawford's family. Or the protesters who have been filling the streets night after night and shutting down police precincts in a show of focused and necessary rage.

Because the cops aren’t sorry. We know they’re not sorry when Follmer goes on national television and calls the killing of a 12-year-old black kid (a “male”) holding a toy gun “justified.” We know they’re not sorry when they explain away the use of deadly force against an unarmed 18-year-old by calling him a “Hulk Hogan” who grew stronger as each bullet entered his body. We know they’re not sorry when they try to ban a public official from attending police funerals because he didn’t fall sufficiently prostrate in defending the officer who choked a father of six to death because he had the audacity to say, “I’m tired of it. It ends today.”

But the cops should be sorry. Not just because remorse is a human and healing emotion and a signal that law enforcement recognizes when it has done harm. But because it’s the last hope they have for credibility with a public that is increasingly aware that the police act with impunity, and that there is nothing brave or honorable or just about the regular murder of unarmed children in playgrounds and dads on street corners and guys in their own buildings and the bathrooms of their own homes. The facade of “to serve and protect” is falling away, being replaced by the more stark and violent reality of how policing really works (or, really, doesn’t work) for people of color.

I don’t mean to overstate the case. This is a potentially transformative moment, but I’m also aware of how stacked the system is. And how complacent people, mostly white people who aren’t touched in the same way by this violence, can be in the face of gross injustice. Even minimal reforms, like the appointment of special prosecutors to handle state violence cases, an incentive structure that doesn’t reward cops for shooting first and asking questions later or using federal funding to compel police departments to alter current infrastructures and training procedures, will take an extraordinary amount of time and struggle.

But people are out doing the work. And the reality is the people protesting, people like Hawkins and thousands of others, aren’t asking for apologies from cops when they kill with impunity. They are demanding accountability from a system that empowers cops to kill with impunity. And that’s something the cops can’t control anymore. The narrative has escaped them as the public has made its demands increasingly clear: It ends today.

I’m reminded here of what Kimberle Crenshaw told me recently about the “levers and dams” that might be used at this moment to redirect power, namely taking some from the police and putting it back in the hands of communities:

What are the political levers available for us to break these moments when the systemic dimension of this just reproduces itself, that amplifies the anti-blackness that’s in the culture?

Are we stuck with this all through the system, or are there ways to build dams into this that redirect racial power in a different direction? Whether it’s episodic in cases that are more high-profile, or more systemic. We figure out ways that the institution of policing had dams put in them so that the reproduction of this kind of culture has some kind of cost associated with it and some possibility to divert some of these energies in a different direction.

These are the kinds of conversations that Follmer isn’t willing to engage in, instead repeating the stock line that the killing of a child on a playground was “justified” and hoping people will believe it and go back home. But people aren’t going home. They are, as Jeralynn Blueford, the mother of Alan Blueford who was killed by an Oakland police officer in 2012, said this week, working to "disrupt business as usual" and hold space until these demands are impossible to ignore. And, like Follmer, they're not apologizing to anybody.

Shares