Johann Rupert, the owner of Cartier, is worried that the commoners are ready to run the jewels.

Speaking last Monday to the Financial Times Business of Luxury Summit in Monaco, an event reported on by Bloomberg, the South African billionaire said the social dangers created by the entrenched structural inequities of late capitalism “keeps me awake at night.”

“How is society going to cope with structural unemployment and the envy, hatred and the social warfare?” he said. “We are destroying the middle classes at this stage and it will affect us. It’s unfair.” Continuing in dire terms, he said: “We’re in for a huge change in society. Get used to it."

"And be prepared.”

So it was that Johann Rupert—worth an estimated $7.5 billion as owner of more than 20 luxury brands—worried aloud to the congregated capitalists that luxury-goods markets will suffer during widespread unrest and class war, and that, as Bloomberg paraphrased, “the rich will want to conceal their wealth.”

But that might be even a little too optimistic, according to Cartier's top customer and unpaid advertiser Jay Z.

Jay, while rich and often Cartier-adorned, maintains a more street-level perspective than Rupert, and he concurred with the Cartier chief’s assessment during a 2013 appearance on “Real Time with Bill Maher.” “I don’t really want to scare America, but the did the real problem is there's no middle class, right?” he said. “So that the gap between have and have-nots is getting wider and wider.”

But that’s not the scary part, and Jay put the threat in much more dire terms: “It's going to be a problem that no amount of police can solve, because, you know, once you have that sort of oppression, you know, and that gap is widening, it’s inevitable that something is going to happen.”

Jay foresees a problem that the state will not be able to contain. A revolution, in other words, or at least an uprising, the moment at which the state loses its grip on power and “no amount of police” can bring order back.

Earlier this month, Salon’s Elias Isquith spoke with veteran journalist Chris Hedges, who, like Jay Z, described the untenability of the current economic trajectory and the incipient “revolutionary moment” that has resulted: “If you read the writings of anthropologists, there are studies about how civilizations break down; and we are certainly following that pattern.”

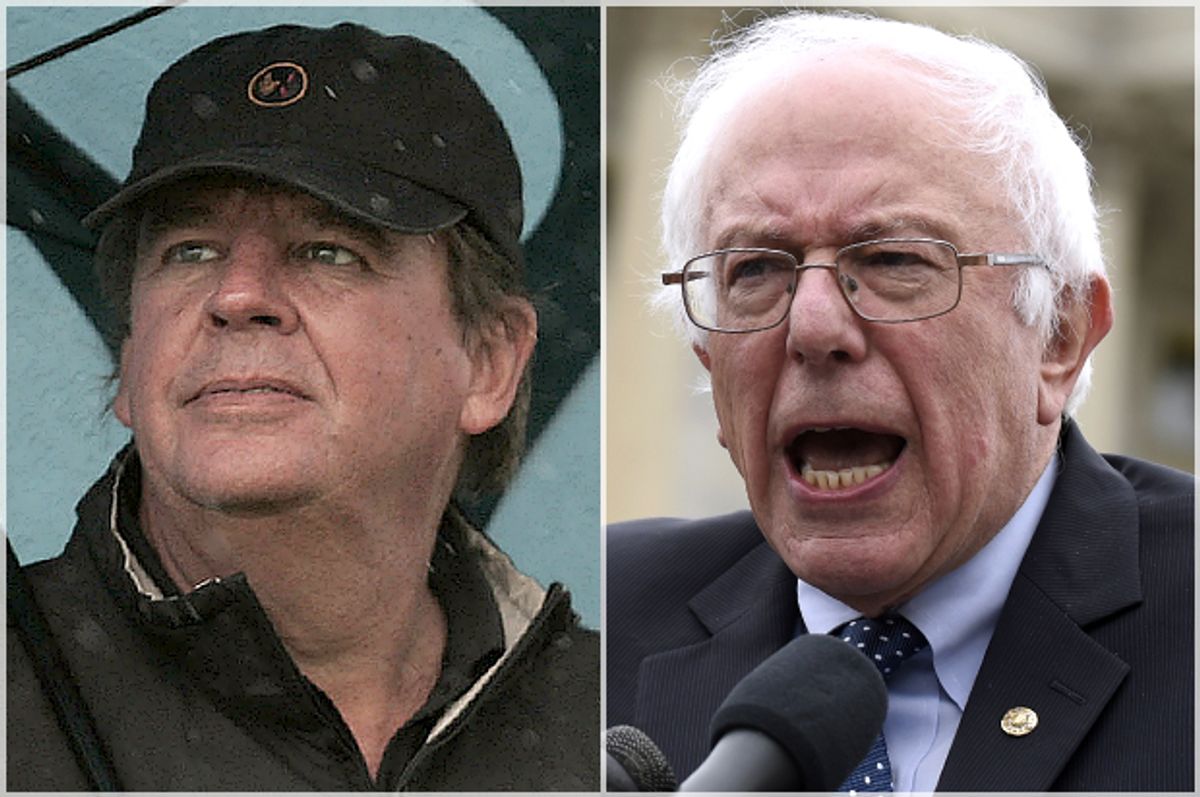

The “revolutionary moment” has even begun to imbue the 2016 presidential campaign with a hitherto unseen character of insurgency from the left. Hillary Clinton’s most credible challenger in the early going, democratic socialist Senator Bernie Sanders, calls for a “political revolution” against what he calls oligarchic rule. What's especially interesting is that Sanders is relying here on a rhetoric that is actually echoed by Johann Rupert.

“We cannot have 0.1 percent of 0.1 percent taking all the spoils,” said a Sanders-esque Rupert at the Monaco event. “It’s unfair and it is not sustainable.”

Sanders has relentlessly hammered these same points on the campaign trail, echoing Rupert’s charge that the conditions of the “new normal” mean that the elite reap most of the economy’s gains created by the rest of us: “There is something profoundly wrong when the top one-tenth of 1 percent owns almost as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent and when 99 percent of all new income goes to the top 1 percent,” he told the thousands gathered at his campaign announcement in Vermont in May.

Rupert might be correct in his assessment of social conditions and their eventual effects, but his imagination still only extends as far as his own businesses’ sales and his customers’ worries about conspicuous wealth. But whether or not you’re wearing a Cartier bracelet might be the least of your worries when the very society and manner of exploitation on which your wealth and safety depends is threatened with revolt. Rupert’s revenue and the accessory game of his elite customers are not the only victims in a revolution. The danger is far more broad, for everyone involved.

Revolutions are something to avoid if possible, something to render unnecessary by correcting the conditions out of which they emerge. But Rupert, as least as the reporting went, did not propose anything to ameliorate the explosive conditions he so fears. The revolution he worries about is not here yet. It could be avoided, provided the elite sort who pal around in places like Monaco to talk about their toys get to remedying the clearly identifiable causal factors.

In fact, they might consider advocating for politicians like Sanders, if they’re Americans, or his counterparts in other countries if they’re not. Sanders’ democratic socialism, modeled on Scandinavian systems, is, in the end, capitalism. There are still corporations and profits, rich and not-rich, wage-earners and owners and everything that makes capitalism capitalism. It just places bounds on how poor and powerless and how wealthy and powerful people can get.

It’s a compromise, what Sanders proposes, not a revolution. The candidate’s proposals surely sound abhorrent to the Cartier crowd, but they might consider the alternative that Rupert fears. And that frightening eventuality, given our current course, is not something fantasized by Occupy activists and anarchists; the threat is already on its way if you ask Rupert, Jay Z, or Hedges; or if you ask a former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, a former National Security Advisor, or the Davos crowd.

It seems that the rich and powerful are beginning to recognize the grave error in the direction they’ve led governments and economies. If this threat is real and impending, we have two ways to address it: either in the halls of legislatures or in the streets. The former would be merely uncomfortable for the rich, but the latter would be dangerous, unpredictably so. Uprisings aren’t polite. They tend to invite themselves over, and Rupert’s customer’s tennis bracelets are the very least of their concerns at that point.

Shares