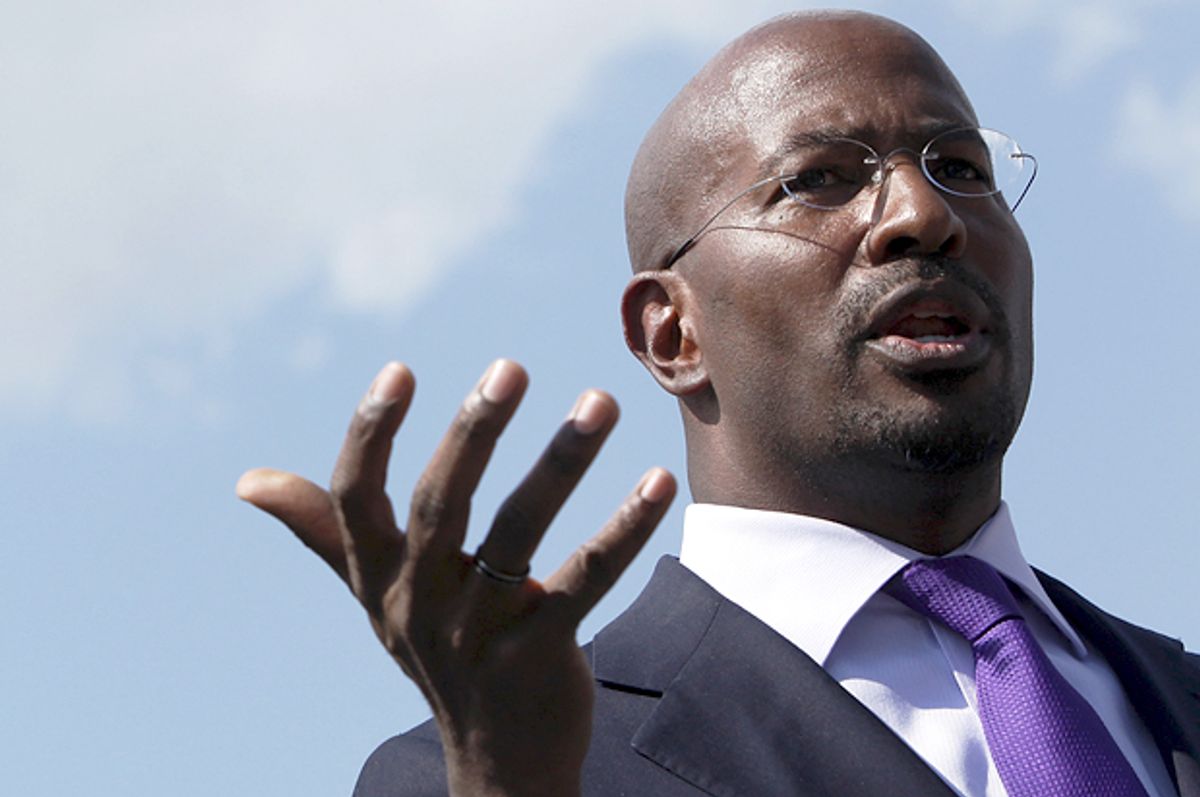

In an Op-Ed published by CNN.com last month, Christine Leonard, the executive director of the Coalition for Public Safety, and Van Jones, a former green jobs adviser to President Obama and the president/co-founder of #cut50, claimed that "a historic surge of momentum" had made "bipartisan criminal justice reform" a real possibility in Washington, D.C.

Noting the president's much-publicized efforts to raise public consciousness of the problem, the significant number of pro-reform figures among the leadership of both parties, and polling that shows Americans of all stripes — Democratic, Republican and Independent — want to see systemic changes, Jones and Leonard argued that after "[d]ecades of failed policies and wrongheaded politics," America had finally "reached a tipping point in the quest for justice." But though the culture has "tipped," they wrote, there was a lot of work left to be done.

One piece of that broader effort will take place in mid-November, when #cut50, Operation New Hope and the Ford Foundation will come together to launch "Operation Reform," a bipartisan two-day summit for experts and activists to discuss systemic and realistic fixes. And many reformers also hope Speaker Boehner will make good on his promise to bring the Safe Justice Act up for a vote in the House soon. If the bill passes, and if reports of Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley's willingness to compromise are true, change may arrive sooner than you think.

Recently, Salon spoke over the phone with Jones about #cut50 and the Safe Justice Act. Our conversation, which also touched on reformers' strategies and the relationship between the progressive establishment and the Black Lives Matter movement, has been edited for clarity and length and can be found below.

What is #cut50?

#cut50 is a campaign to safely and smartly reduce the U.S. incarcerated population by 50 percent. The key for us is using proven, bi-partisan solutions as the basis of the campaign. So, we're a bunch of progressives at our core, but we work hand-in-glove with everybody from [Sen.] Cory Booker to the Koch brothers [for] change.

Actual bipartisanship is pretty rare nowadays. So how did this project get started?

I was working with [former Speaker of the House] Newt Gingrich on CNN on a show we were doing together called "Crossfire," and Newt and I basically disagreed on every topic — except for the problem of excessive incarceration.

And we had so many discussions in which he helped me understand that conservatives were becoming very uncomfortable with the direction of things. He pointed out that it was beginning to look like the incarceration industry was a big, failed government bureaucracy that was gobbling-up more money and stealing more liberties without producing defensible results; and that everyone [on the right], from fiscal conservatives/libertarians to Christian evangelicals, was unhappy with how the criminal justice system was functioning.

And you're concentrating right now on getting the Safe Justice Act through Congress?

That is our current focus, yes.

I had some questions about the bill, or rather some of the strategic decisions it represents. For example, why such a focus on the policies of the federal government when so many of the people who are incarcerated right now are locked up in state programs?

Because if you have President Obama in the Rose Garden, with Senate Majority Leader McConnell and Speaker of the House Boehner next to him, signing a federal bill — with law enforcement and formerly incarcerated people in the front row — that sends a huge signal to the rest of the system; that means every governor, sheriff, county executive knows that the water is safe and that they can push their own set of reforms.

So what are the points of agreement, policy-wise, that both sides are supporting and trying to implement?

Well, from a data-driven and evidence-based point of view, lengthy mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenses cannot be justified any more. We no longer let judges judge; prosecutors have massive super-weapons to aim at anybody who's caught with any quantity of drugs; and we've basically criminalized addiction.

That's a point where I think conservatives and progressives agree — that it doesn't make sense to put somebody in jail for 30 years for a nonviolent drug offense. You only get 25 years for shooting a cop. So rolling back some of those mandatory minimums is common ground.

That raises another question I have about the strategy. We talk a lot about nonviolent drug offenders, and I get why, since those tend to be the most sympathetic victims of the system, in the abstract. But the problem can't really be solved without dealing with violent offenders, too, right?

Because you can't split a log with the fat end of a wedge. Probably 80 percent are nonviolent drug offenders — they just didn't get caught [laughs]. So I think people can really have sympathy and understanding for those kinds of mistakes.

The tougher offenses that people commit, we have to have a discussion about those at some point as well. Since about 90 percent of these people are coming home anyway at some point, how long do we want to keep people [incarcerated]? And what can we do to make sure that when people come home, they're able to stay out of trouble?

So at some point it has to extend beyond nonviolent drug offenders; but I think that it's important that we try to start where there is common ground.

OK. So where else is there common ground between the left and the right?

Also the fact that not only do we criminalize addiction but we also criminalize mental illness. We have a lot of people who are in prison because they're mentally ill — and who get worse while they're incarcerated, not better. That's another area of common concern.

And everybody agrees that when people return home from prison, they need to be leaving better than they were when they went in, and more capable of being a good citizen than they were when they went in; and that is just a massive failure across the board. Corrections does not correct anything any more (if it ever did).

And lastly, there are issues about [the experience of] confinement, issues including prison rape and the abuse of solitary confinement.

How do you and your partners decide how to divide your energies between keeping people out of prison and changing what it's like to be in prison?

The whole system is the problem, which is why we're fighting for a comprehensive [reform] bill. You do have, unfortunately, some reluctance on the part of both Sen. Chuck Grassley and Rep. Goodlatte to really take up a comprehensive bill. But the reality is that a series of tiny, piecemeal bills — some of which may pass, some of which may not — is not going to get us to the outcome that we want.

Well, that brings me to something that I wanted to ask you about, because it's an aspect of the criminal justice reform movement — and especially its more avowedly bipartisan corners — that gives me pause. Namely, it's the emphasis often placed on how criminal jutice reform will reduce costs. Do you ever worry that, by focusing so much on costs, the movement makes itself vulnerable if the crime rate were to reverse itself from its longtime downward trajectory?

That focus on costs would absolutely be a thin foundation on which to build the movement. But the interesting thing is, that doesn't seem to be the main motivator [for conservatives].

Let me put it this way: If we were just talking about trying to find a low-cost solution, maybe we could just put a chip in people's heads and, y'know, bug-zap them in their homes; that might be the lowest-cost solution. But I don't think [cost-cutting] the full motivator for either the left or the right. There's a stereotype of conservatives only caring about money; they may argue in those terms, but when you talk to them, there's a whole array of motivations for the conservatives who are engaged.

I wanted to ask you another question about the experience of working in a bipartisan way on this issue. How do you handle race? It is obviously so central to this whole dynamic, but we usually try to keep race on the sidelines when the goal is maintaining bipartisan support for something. Do you try to avoid it when working with conservative partners?

Well, whether you're talking about Sen. Rand Paul or Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner, they've been willing to say the obvious, which is that [our criminal justice system delivers] an especially horrible set of consequences to people of color — and young men of color, in particular.

So I think that, from a rhetorical point of view, more conservatives are comfortable acknowledging the obvious. From a solutions point of view, we'll see how they respond to policies that are explicitly racial in their intentions. But, right now, just trying to reduce the overall size and scope [of the criminal justice system] is the main thing.

But, listen, at #cut50, we talk about race all the time, and it doesn't seem to have blown-up any of our relationships [with people on the right]. Where we disagree, we just disagree. People have so little experience having a decent conversation ... that they can't imagine that people could actually sit down and actually work together even though they don't agree on everything.

What do you mean?

I just don't agree with the Koch brothers on environmental policy — and I fight them on it every day. I don't agree with them on their "$1-for-1-vote" view of American democracy — and I fight them on it every day. When I'm on the phone [with their representatives], I'll sometimes mention that [my team] was just talking about how to beat them on this thing or stop them on some other thing. And they'll laugh and indicate they've had similar conversation on their side.

But then we talk about the one thing we want to work on together. That's how democracy is supposed to work. A dictatorship, everybody has to agree; a democracy, nobody has to agree and where you disagree is where you're supposed to fight. That is very basic. But our culture has become so addicted to conflict ... that the idea that people who passionately disagree about something could work together [on something else] — they can't get their heads around it.

On that conflict-addiction point, I wanted to ask you for your thoughts about the moment between former Gov. Martin O'Malley, Sen. Bernie Sanders, and Black Lives Matter protestors at Netroots Nation last month? Was that an example of the kind of short-sighted fighting you're criticizing? Or was that a good thing because it pushed the Black Lives Matter movement's issues to center-stage?

That was an absolutely important and necessary moment for the Democratic Party.

I've been warning the white populists in the party, behind the scenes, for several months, that their continued insistence on advancing a color-blind, race-neutral populism was going to blow up in their faces; that they literally are in the middle of the next chapter of the black freedom struggle; and that they have to acknowledge it.

The next chapter in that struggle is being written before our eyes. And to be a part of a political party that has to have 95 percent of black voters vote for Democrats every presidential election, and to refuse to acknowledge that? It's stupid and wrong. And I've been saying that behind the scenes for months: You cannot have people — even people I love, like Sen. Elizabeth Warren — stand-up and describe the 1950s as some kind of utopia to this generation of African-Americans. It's not going to work.

The Obama era of black silence on issues of specific important to black people is over. Period. We will not accept trickle-down economics from the right wing and we will not accept trickle-down justice from white populists in the Democratic Party. We have specific pain and specific problems and they need to be addressed specifically. And every other part of the [Democratic Party] coalition gets that treatment without controversy.

Go on?

There's no controversy about specifically addressing the needs of the Latino community with regards to immigration; there's no controversy about specifically addressing the needs of our lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender sisters and brothers when it comes to marriage and other rights; there's no controversy about specifically addressing the interests, needs and passions of the women's rights movement; there's no controversy about specifically talking about the environmental agenda.

We are the only part of the coalition that if you speak specifically about our issues, people get uncomfortable. And that's not fair. So that moment [between Sanders and the Black Lives Matter protestors] was incredibly important and had to happen — and Bernie Sanders should know better.

How so?

How can you be a politician of his age and standing, and want to be president of the United States, and in a part as diverse as [the Democratic Party] and then give speeches that sound like they come out of the 1930s when it comes to race? You can't do it that way.

Listen, real economic populism that tries to deal with the question of income inequality cannot fail to talk about the criminal justice system. I mean, a major driver of income inequality — and certainly racial inequality — is that you have whole categories of people who are being herded off to prison for stuff that kids are doing on Ivy League campuses right now. But they have nothing on their records, while you've got poor kids, living 20 minutes away, who are called felons. As long as that's happening, you will have income and racial inequality in this country.

I'm focusing on Sanders here but, as you said, this isn't really a problem specific to him so much as it is one generally for white, populist Democrats. Are you seeing any signs that this bloc of the party coalition is starting to understand the issue here?

I think that, at least rhetorically, that was the last that you will hear of this kind of bullshit — trying to replace "Black Lives Matter" with "All Lives Matter" and all that nonsense. That's over.

Shares