It’s hardly the first, but it’s a gargantuan, wide-ranging volume that anyone with an interest in the field should be aware of. “The Big Book of Science Fiction” collects more than 100 stories, beginning with an H.G.Wells piece from 1897 and closing with a 2002 tale by the Finnish writer Johanna Sinisalo. In between are well-known authors like Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Philip K. Dick, Ursula Le Guin and William Gibson, as well as writers not associated with the field (Borges, Karen Joy Fowler) and authors from two dozen other countries. (The editors say they wanted to include a story by Robert Heinlein, but were not able to get his estate to give them the rights.)

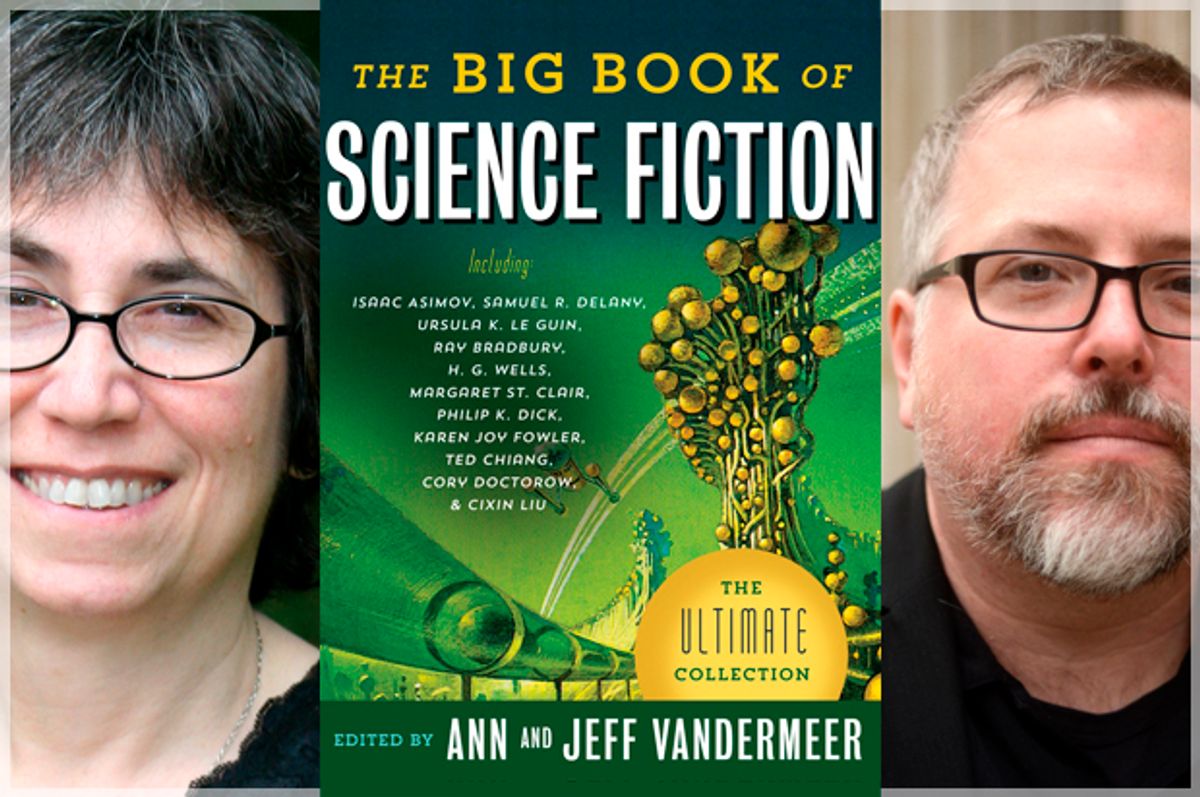

The anthologists are another reason for excitement: Ann VanderMeer is one of the best-regarded editors in the field – she’s a former editor-in-chief for Weird Tales who now acquires titles for Tor.com. Jeff VanderMeer is the critically acclaimed and bestselling author of the Southern Reach trilogy.

We spoke to the editors from New York, where they were on a book tour. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

There are all kinds of ways to define science fiction, and it’s been described in different ways in different periods. What was your working definition when you put together this book? What was within the bounds for you?

Jeff: There’s always a lot of infighting about that question, both within the genre community and outside of it. So we decided to keep it pretty simple. We didn’t want to make any grand claims, like that Gilgamesh was the first science fiction book, or things like that – the kinds of claims that have been made in the past to legitimize science fiction.

We just thought, really, science-fiction — if you want the most basic definition — is simply any fiction that takes place in the future. We don’t have a lot of steampunk because it seems to have more of a fantasy feel. And there are far-fiction stories where the science is almost indistinguishable from magic, and we thought we’d reserve those stories for a fantasy anthology down the road.

But it eliminates discussions we don’t find that useful about the difference between genre and mainstream.

One of the things that sets your books apart is the huge amount of international science fiction. I wonder if you can talk about a country from which the work has been especially strong, and describe what’s distinctive about it. How different is it from the Anglo-American tradition?

Ann: I think a lot of people can agree that there’s a lot of amazing science fiction that’s come out of Russia in the past few decades. One of the reasons that’s happened is that it was a very good way for the writers in Russia and the Soviet Union to tackle these issues in a way that wasn’t going to get them put into prison. They were still censored in many ways, but that was one thing you saw, not just in the Soviet Union but also Eastern Europe.

We’ve also found many writers from South America – Brazil, Argentina, other countries. We found South American writers to be a little more playful and absurdist.

It sounds like the spirit of Borges is still alive down there.

Jeff: It is true that the Latin American impulse is not driven by a conflict-driven plot or by the kind of adventure tradition that the American pulp fiction still influences, sometimes in very good ways.

There have been political tensions in the field for decades, but the last few years has seen them become more explicit. A group of macho reactionaries tried to take over the Hugo Awards, while the Nebula awards this year went almost entirely to women. Are things coming apart, or being resolved? How significant is all this?

Jeff: As anthologists we take the long view; it’s really useful. There have been Hugo controversies before, like in the ‘50s and ‘60s when the New Wave came around. What really happens is that the controversies get subsumed by whatever becomes successful either critically or commercially. It can seem to the participants that they’re in a life and death struggle. But in the case of the Hugos, it’s really irrelevant to where the energy is in the field.

It’s like what used to happen in the technology and gaming industries – you have a few quote-unquote token women, and that was just fine for the men involved. But once you get beyond 30 or 35 percent, it’s perceived as a threat.

In the last 15 years, women and women of color have come into the field in unprecedented numbers. But what this means is that we’re in a full flowering of potential for science fiction because we’re getting science fiction from so many different kinds of voices. So what this era will be remembered for is that.

As for the Nebulas being all women, I’ll be absolutely honest, in terms of short fiction especially, the writers in science fiction I think are the best are almost all women, for whatever reason. I don’t see that as ideologically based.

Ann: I’m in full agreement with what he’s saying. The way I look at science fiction, I want the world to be as full as it can possibly be. I don’t like to put constrictions and barriers and borders around things. I embrace all the different voices and points of view. I would like everyone to have a piece of the pie.

For a book like this, you’re looking back over a full century, and taking in almost the entire globe. To what extent did your early 21st century perspective — where we’re conscious of climate change — shapes your choices of what was important?

Jeff: Yes, definitely. There are certain things that become more or less relevant and make a story more or less appealing to a modern reader. So if we had two stories of equal quality, we would include the one that had more of an environmental theme. And there were other writers, like F.L. Wallace, who had a story called “Student Body” that was completely overlooked when it came out, but now it’s prescient, seeing the future. While a lot of what was award-winning at that time really doesn’t speak to a modern audience at all.

Ann: It’s quite interesting that there were a lot of stories that did deal with global warming and the environment back then. I also remember a novel I read years ago that made me a lot more conscious of the environment. It was “Nature’s End,” by Whitley Strieber and James Kunetka. I can’t remember details, but I remember how it struck me when I read it, in the ‘80s or ‘90s.

I immediately got involved in the World Wildlife Fund. I also think science fiction, and fiction in general, can make a difference. It can make a difference to how people perceive the world, and it can move them to action. I know that in my case it did.

Shares