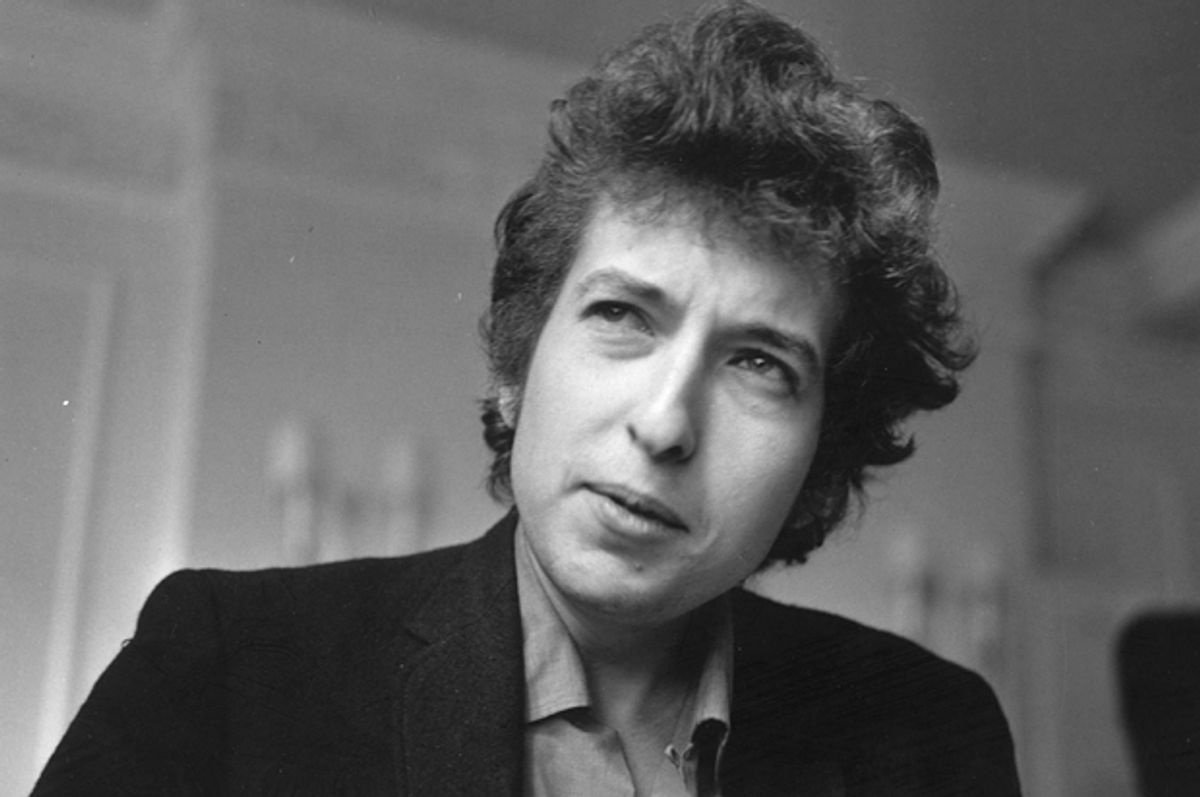

When Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize for Literature last month, he became the first musician and the first American since Toni Morrison in 1993 to win the coveted international award. While it took the Nobel committee — which heralded him “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition” — decades to herald Dylan’s genius, he has been well established in academia for years. The Nobel will likely nudge him even deeper.

“The Nobel legitimates him somewhat, but Dylan had already crossed over to literary or academic respectability,” said Evelyn McDonnell, a onetime Village Voice rock critic who now heads the journalism program at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. “This might be the final stamp of respectability that takes away their last opposition.”

The first university class on Dylan is believed to have been taught in the 1970s, and in 1998 Stanford hosted what is thought to be the first academic conference of Dylan studies. In addition to tomes of lyric and sheet music, and Dylan’s memoir, “Chronicles Volume 1,” there are about 1,000 books on Dylan in English. Besides stand-alone Dylan courses, there are classes on the history of rock, on the '60s and on American studies in general in which he figures.

“Since [Greil Marcus’ book] "Mystery Train," it’s become pretty clear how you fit Dylan into a serious discussion about American culture,” McDonnell said.

But the complicated question seems to be which Bob Dylan we are taking about. Is Dylan a poet, a musician or a representative American? More specifically, is he the socially conscious folk songwriter, seeking racial justice in early acoustic songs? The brash, surreal, electric troubadour? The man from Minnesota who left home for Greenwich Village and embodied a certain strain of American myth? The ethnic Jew who for a time became a born-again Christian?

Is he a man of the page — whose work needs to be "close read" like John Donne’s? A creature of the stage, whose electric guitar playing at the Newport Folk Festival (and in a series of triumphant and controversial British shows) scandalized his fans and who has led what has been called The Never Ending Tour? Or the brilliant and frustrating figure who abused and stonewalled reporters sent to interpret him?

Over all, Dylan has proved to be as complex and mercurial a figure as he appears in the movie “I’m Not There,” in which he is portrayed by six people, including an Australian woman and a black teenager.

“To me Bob Dylan’s greatest creation or invention is Bob Dylan himself,” said Don McLeese, a veteran music writer who taught “Journalism and Bob Dylan” in 2014 at the University of Iowa and is preparing to offer the course again next fall. Dylan, he said, was created by his songs, music and actions but also by the media — by the writers, filmmakers and documentarians who have tried to capture him. “Media,” McLeese as termed it, “that Dylan has both resisted and manipulated.”

As a result, there is no real consensus vision of the musician. He said, “Different people perceive a different Bob Dylan,” including his students. “I try to help them put the entire puzzle together.”

***

Forget Bob Dylan, huffing on his harmonica. For hundreds of years the academy didn’t know what to do with literature in English. Studying (or “reading”) literature at Oxford and Cambridge — and the ivy-covered American schools that emulated them — meant “the classics,” the works of Greek and Roman antiquity like Homer, Sophocles and Ovid. Even in the early 20th century after the now-canonical British writers landed on the list of what was considered worth teaching, it was decades before American writers like Longfellow and Hawthorne were considered of sufficient weight.

There were back and forth fights over figures as straightforward as Charles Dickens. As late as World War I, the English literature taught at Oxford ended with the Romantics. (In many British universities, Anglo-Saxon poetry was required until around 1970.)

Pre-rock musical genres like the blues and jazz endured similar fights to earn academic credibility, and in some ways are still undergoing them.

Some of this academic stuffiness was still alive when Anthony DeCurtis completed his English doctorate degree just at the time of the release of Dylan’s “Slow Train Coming” record. When he entered the academic job market, he found that his interest in contemporary American literature — Philip Roth, Don DeLillo, Toni Morrison, others — put him near the end of the queue. “The question I got most often was, ‘Which of these authors is likely to last?’” When he brought up Brian DePalma’s film “Carrie” at an academic conference back then, he was sneered at, he recalled.

A turning point that opened the door for Dylan was — ironically, given his fraught relationship with feminism — what is sometimes called “Madonna studies.” This interdisciplinary field, exploring Madonna's songs and politics and especially her women’s-empowerment narrative, began to filter into academia in the late 1980s.

Around the same time, French literary theory, including deconstruction and post-structuralism, which looked at culture with new methods infiltrated academic English departments. Then cultural studies invaded campuses. “Once theory become a really significant part of the humanities scene, everything is fair game,” said De Curtis, who will teach a Dylan course at the University of Pennsylvania. “Whether the text is Bob Dylan or the text is Chaucer, you're coming at it with the same set of analytic skills. The pop culture doors just blew open.”

McDonnell pointed out, “In a lot of ways popular music studies has gone way beyond Bob Dylan by now.” She pointed out that her university today “has a president who makes EDM" or electronic dance music.

When DeCurtis shared with colleagues his fear that his Dylan course was too contemporary for an Ivy League school, he recalled, “My friends would be laughing." They said teaching Dylan is almost as old school as teaching Shakespeare. "There are classes offered regularly [around the country] on Beyoncé and Tupac.”

***

Of course, even with the transformations inside academia and the inevitable triumph of baby boomers' I-was-at-Woodstock taste, it’s still not clear what the best way is to teach Dylan.

McLeese teaches Dylan as a media figure and assigns a volume of his Rolling Stone interviews. He also shows the 1967 documentary “Don't Look Back,” in which the musician patronizes journalists (and just about everyone else) and discusses his own experience with Dylan in the '80s before the release of the “Empire Burlesque” album.

“Obviously, I was scared to death because I’d seen 'Don't Look Back' and had read interviews with him being elusive and mysterious," McLeese said. "He was a terrific interview, soft-spoken, but he said at one point that he liked to talk. He also had the weakest handshake of anyone I’ve ever met.”

DeCurtis, by contrast, asks students to "close read" Dylan’s songs “to get inside them.” A course at St. Mary’s College of California, taught by the poet and musician Chris Stroffolino, explored Dylan’s music in relation to his peers and inheritors, including Conor Oberst of Bright Eyes.

Other courses consider Dylan’s relationship to his early girlfriend Suze Rotolo, Dylan at Newport, Dylan as a Jew — or Dylan (by former Oxford professor and Victorian poetry authority Christopher Ricks) and biblical sin.

Not long ago, “Hamilton” star Lin-Manuel Miranda appeared on "Saturday Night Live" as a substitute teacher, greeting a class at an urban high school with announcements of his down-with-the-kids hipness: When he declared his shared fondness for “dope beats” or tried to startle the students by proclaiming William Shakespeare the first-ever rapper, they rolled their eyes because they had heard it all before.

It may be that Dylan hits a funny sweet spot in academia today: To many professors, he still stands for literary ambition and '60s rebellion. And for many students — born in the last years of the 20th century — he is so distant from the streets where they live he might as well be John Keats.

Shares