In conjunction with the various sanctions President Obama unveiled Thursday against the Russian government in response to that nation's alleged hacking of Democratic Party servers, the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security released a report that supposedly provides evidence pointing to the Russian Federation as responsible for the cyber-attacks.

But the document, termed a “Joint Analysis Report” (JAR), contains nothing of substance pointing to Russia as responsible for any of the attacks and will do little or nothing to assuage public doubts about who conducted the security breaches.

Furthermore, the analysis appears to be a re-release of an earlier report that was distributed confidentially in October, and contains no newer information. A related webpage set up by a DHS agency to accompany the Thursday release mentions that the report was originally distributed on Oct. 7.

The 13-page JAR appears to be more of an advisory for government server administrators than anything else. Private-sector reports about the DNC-Clinton hacks have been much more thorough and informative.

Security academic researcher Thomas Rid, a professor at the University of London who has written extensively on evidence indicating Russian involvement in the DNC hacks, criticized the released document on Twitter, saying that the U.S. had “erred on the side of caution today and did not release the best evidence they have.”

He further added: “It would’ve helped, really, to publish a thorough, precise, historically informed and technically honest attribution report in plain English.”

That simply is not what the DHS-FBI document is. Instead, after a brief summary, the report provides a general description of what happened in attacks, saying only that they targeted “a U.S. political party” and attributing them to two separate organizations within the Russian intelligence apparatus. Those groups are termed “APT28” and “APT29.”

The second section of the report is a description of one of the attackers’ methods, a common and unsophisticated practice that has been in use among “black hat” hackers for more than a decade. The technique, called “spearphishing” by the security industry, is a technique whereby an email is sent to a target claiming to be from a legitimate source that actually contains a virus-infected file or a link to a fraudulent website designed to steal passwords.

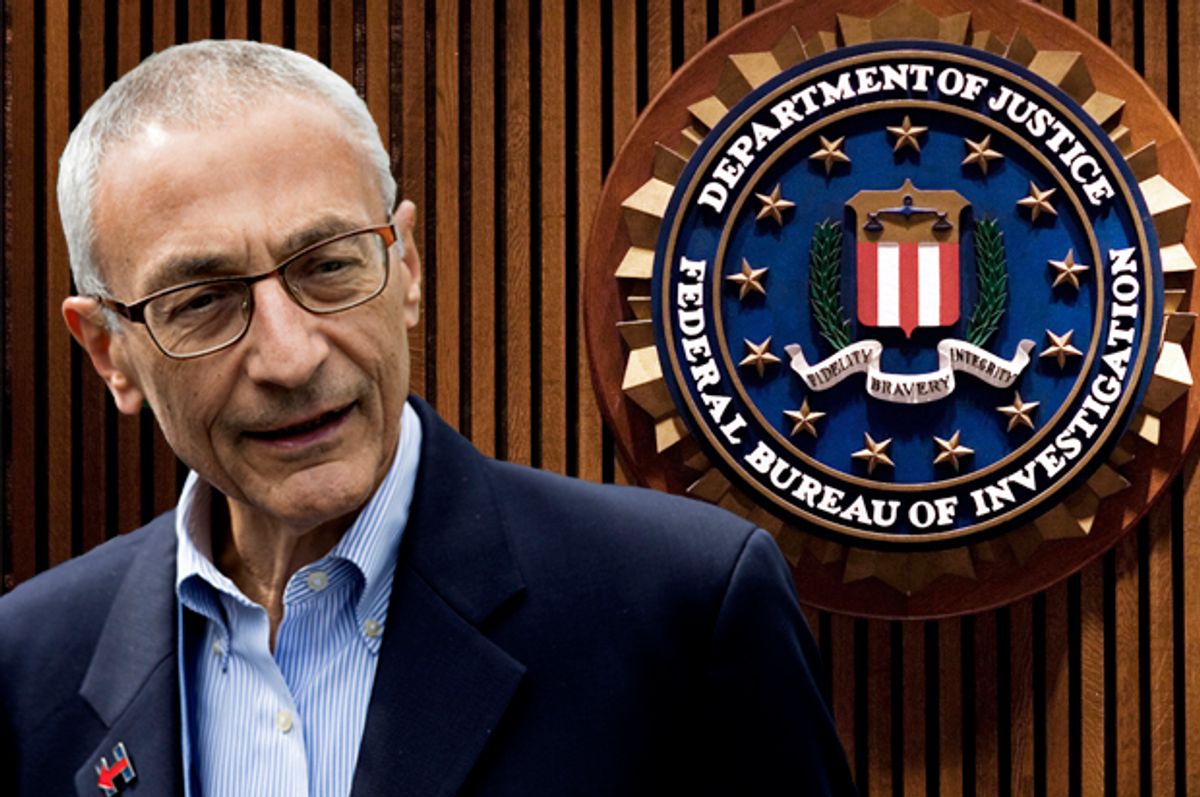

One of the tens of thousands of messages released by WikiLeaks from the email account of Hillary Clinton campaign chair John Podesta seems to indicate that he may have clicked on one such forged password-reset email.

According to researchers at the private-sector firm SecureWorks, the link Podesta apparently clicked was created via a public URL-shortening service account on the website Bitly. SecureWorks researchers were able to determine that the Bitly account in question had created almost 9,000 links, several hundred of which were sent to addresses under the hillaryclinton.com domain. According to SecureWorks, the malicious website to which scam victims were redirected was controlled by APT28, an entity that the security firm says is probably operating from Russia and is working on behalf of the Russian government. (SecureWorks has not said why it believes this, however.)

None of this information is disclosed in the government’s Oct. 7 JAR analysis.

After describing the general methods of attack, the JAR then lists what it says are some aliases of alleged Russian hacking teams, providing no information about what these groups have done in the past or what techniques they use.

The list appears to confuse group names with techniques and virus names and provides no differentiation between them, implying that the authors appear to think that a virus is also the code name of a hacking organization.

As Robert M. Lee, CEO of the computer security firm Dragos, put it, the list is essentially “a mixing of data types that didn’t meet any objective in the report and only added confusion as to whether the DHS/FBI knows what they are doing.”

The government analysis then refers to some filenames and about 900 IP addresses that it claims are associated with both APT28 and APT29. (The full list of the IP addresses can be downloaded here.) Unfortunately for server administrators and the public alike, no information of any kind is provided about what activities these IP addresses might have engaged in, or when. For all we know — and the distributed knowledge of the Web will probably let us know soon — many of the addresses in the listing are currently owned by innocent parties and have not been involved in cyber-attacks for a long time.

The remaining nine pages of the FBI-DHS report contain nothing more than a collection of tips for securing servers. The advice is sound (though basic for properly trained server admins), but the fact that it comprises the majority of the report that the White House has put forward as primary evidence that Russian hackers attacked American political parties is not reassuring when it comes to confidence in the administration’s decisions.

Earlier in December, White House counterterrorism adviser Lisa Monaco told reporters that President Obama had ordered the various intelligence agencies to provide a comprehensive report about Russian involvement in the DNC hacks and have it completed before President-elect Donald Trump takes office on Jan. 20.

According to CNN, the Democratic members of the Senate Intelligence Committee have requested that this report be made public.

We can’t know for certain how much of that document will be declassified, but whatever is released will need to be more substantive than what was released this week.

Shares