The new millennium may still be on the horizon, but at least one truism can already be ascribed to our new New Age: It's a damned confusing time to be black. Ask anybody -- a single mom who is both vilified for her poverty and valorized for her strength, an invisible and uneasy member of the middle class (me), the increasingly hapless Puff Daddy, with his big diamonds and even bigger scowls, the enormously successful but racially repressed Tiger Woods.

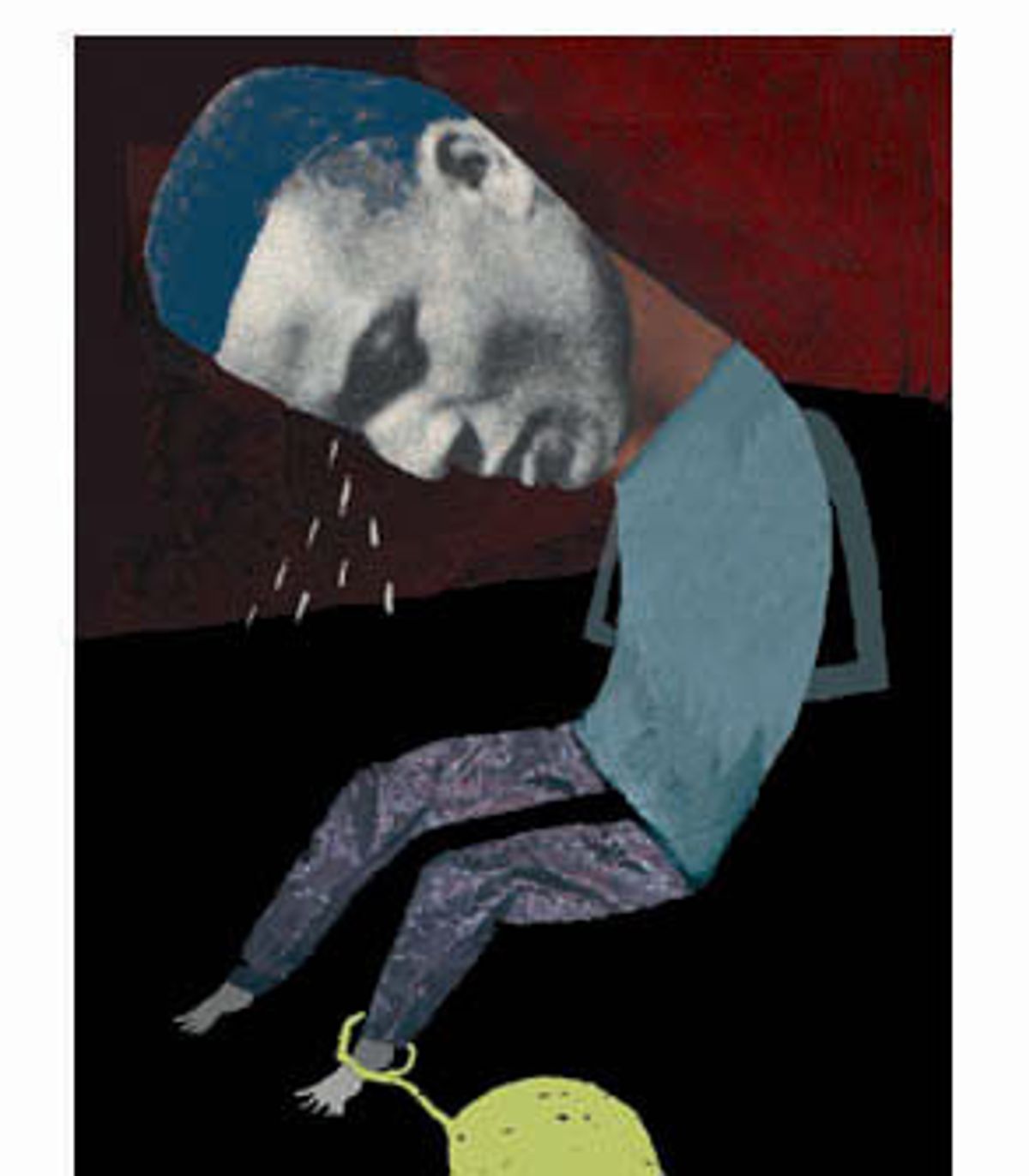

Never before in history have blacks loomed so large in the public imagination and popular culture yet been granted so little space as real people. And, by no accident, never before have they experienced higher rates of depression, homicide and suicide: Black youth in particular have watched their suicide rates explode at millennium's close, increasing 114 percent in the past 20 years.

What gives? More to the point, why isn't anybody asking what gives? If we are truly the nurturing, pro-young-people nation we claim to be, why aren't our political leaders sitting up nights wondering why black men between the ages of 20 and 24 are now killing themselves at 10 times the rate of their female counterparts?

In their new book, "Lay My Burden Down: Unraveling Suicide and the Mental Health Crisis Among African-Americans," veteran psychiatrist Alvin Poussaint and journalist Amy Alexander give us the painfully obvious answer to those questions: lingering racism that translates into a general political disinterest in the fortunes of black folk (except as they relate to crime and other issues that might infringe on the white population's hermetic sense of social security).

But Poussaint and Alexander are more interested in dissecting the complicated dynamics that underlie not just the current Negro problem but the current Negro success. The bedeviling paradox of the past several decades is that as the black middle class has exploded, so has the suicide rate (to say nothing of the homicide rate) among young black men and teens across the economic spectrum. The reluctance to examine -- or even acknowledge -- the connection between our rising prosperity and declining mental health cuts across color lines.

Poussaint and Alexander break the taboo and speak out, albeit carefully, about the possible causes of the current mental health crisis. They theorize that, among other things, the much-publicized split between the black poor and the black middle and upper class in the last generation has engendered a collective, free-floating anxiety and dispiritedness in the black community that are wearing down everybody's well-being.

The spiraling suicide rates, especially among the young, sound a warning bell we have not heard before: Blacks have historically experienced very low suicide rates, despite having endured years of far more blatant discrimination than they endure now. But the self-reliance that has long been the core of black culture and survival -- think blues, black power, gangsta rap -- may now be blacks' undoing.

The psychological effects of what Poussaint and Alexander call "post-traumatic slavery syndrome" that blacks have managed to hold at bay for so long may finally be catching up to us in 2000, 135 years after slavery's end. Add to this a potent legacy of dehumanization, including diehard stereotypes about blacks as "cool," intellectually lacking and emotionally uncomplicated creatures -- expressed today in UPN sitcoms and BET videos -- and mental breakdown seems all but inevitable.

"Undoubtedly, great strength allowed black people to survive slavery and discrimination, but the notion that black men and women can easily handle burdens that would psychologically crush other people has been oversold," the authors write. "The emotional price that they have paid in enduring incredible stresses has been too often dismissed or ignored, and this has hindered the development of mental health services for the black community."

If all this sounds a bit dry and removed, it is at points, but there's no mistaking the passion behind Poussaint and Alexander's quest for a kind of equity that has always been most critical to blacks but has always been hardest to attain: psychological equity.

"Burden" points out that shamefully little research has been done on cause and effect between the state of black mental health and the numerous historical, economic and psychosocial factors that have shaped and continue to shape the black psyche. It is a psyche partly fashioned from neglect, including neglect from a white medical establishment that long viewed blacks as unsentient beings who hardly deserved psychiatric consideration.

As a black woman thrashing with the new class divide and an intermittent but chronic depression that feels as old as rivers, I found the book a relief, an assured voice in a wilderness of purpose and identity I felt I was essentially wandering alone. But the question -- the eternal question -- is whether the issues raised by "Burden" will only circulate among African-Americans. If they do, the problems detailed in the book will compound: Blacks will once again feel the pinch of isolation and most of America will miss the point. At its measured heart the book is asking that we all care, not in order to be altruistic or democratic but to be practical -- black self-regard ultimately and intimately affects everybody else's.

While we all contemplate taking such a big step, here are a few points in "Burden" to tack onto our refrigerators: With middle-class success has come the loss of a segregation-era "social equilibrium" in which everyone in the black community was on the same emotional and expectational plane and thus harbored more collective hope about the future. For cultural and religious reasons, blacks have been historically reluctant to admit to depression and the other d-word, despair, though they have been better acquainted with them than any other group. Our individual state of mind is continually affected by the state of the black nation, which at this point is dominated not by hope and the rising expectations of the middle class but by skyrocketing rates of imprisonment, drug abuse and unemployment.

And guess who has the highest rate of imprisonment, drug use and unemployment? Black young men, of course, the soldiers of the hip-hop nation who amid the distressing statistics are still expected to carry forward the dreams and expectations of the black community. The reality is that far too many of them fail to fulfill these expectations -- or find that even worldly success fails to mitigate their despair -- so it is hardly surprising that it is they who are suffering most acutely in the current mental health crisis. It is they who bear the brunt of America's eternal unease with blacks in general, they who see images of themselves plastered on billboards with lackluster eyes and brooding menace. I see those billboards and feel a direct hit of anger, repulsion, empathy. I feel every bewildering thing at once. To me, and to many others like me, any image of a black person feels like a representation of all black people -- at this point in our evolution we are still not at the point where we can comfortably separate symbol from self.

If that isn't madness, nothing is. Poussaint and Alexander don't fully explicate the nuances of this madness, only because they keep the book to a status report. But it's a start, and despite the sobering picture the book paints of our bruised and once-infallible hope, it's the most hopeful thing I've read in a long time.

Shares