In their 25-year career, Joel and Ethan Coen have taken the expression "leaving the audience cold" as a mission statement, not as criticism. They've consistently put American life, past and present, in the wrong and distorted end of their creative telescope, and usually found the results wanting. Consummate craftsmen, the Coens can be a hit-or-miss proposition. When they hit, they hit hard; when they miss, well, they are still worth watching.

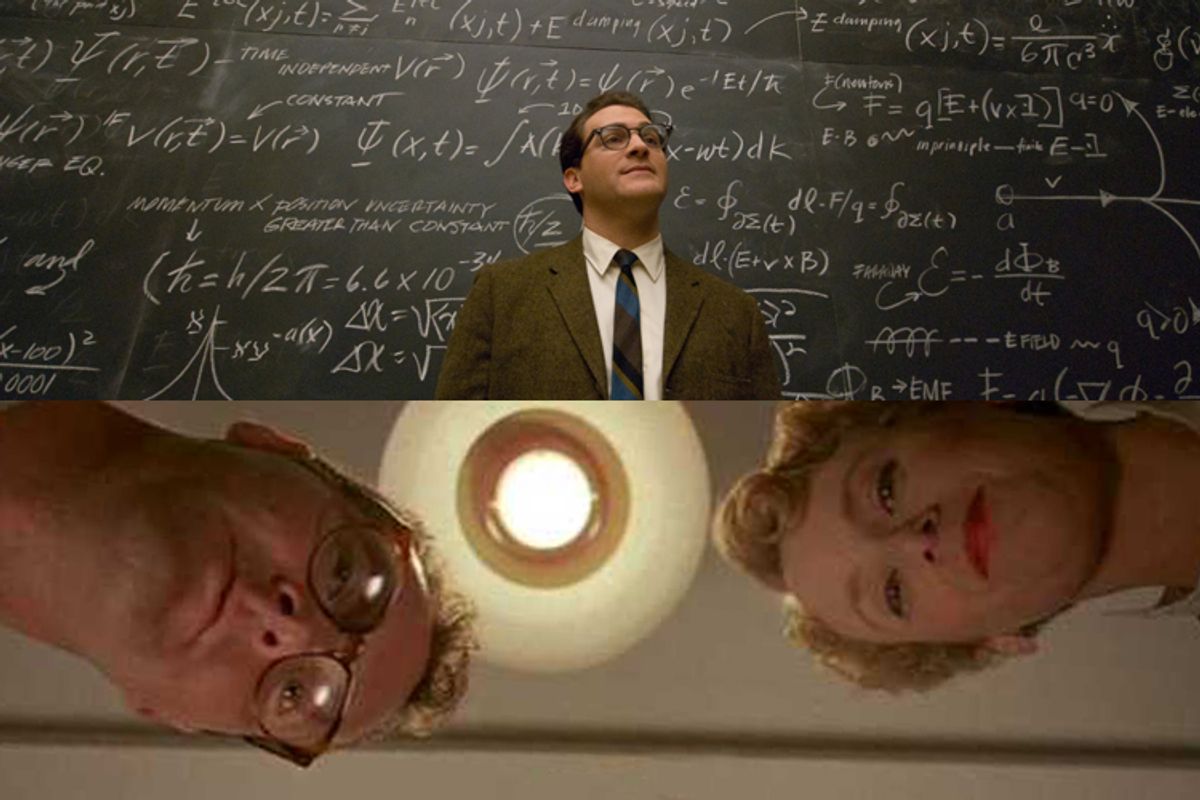

Which brings us to this week's DVD release of "A Serious Man," the latest exercise in Coen Gothic, this time set in a Minneapolis suburb in 1967's so-called Summer of Love.

There is a Dickensian quality to the best of the Coens' films, where every character is just shy of caricature, but somehow their conviction and commitment makes it work. Every director's film needs its "non-submersible" units, in the words of another sublime craftsman, Stanley Kubrick, and the Coens can always be counted on to serve those units up, with relish, on the side.

The beating heart of "A Serious Man" is the travails of Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg), a put-upon protagonist who just wants to detach himself from his nightmarish family life, and the deracinated culture that contains it. Larry's losing battle to just get through the small-town day recalls fellow misanthrope W.C Fields, another Dickensian figure, whose battles in classics such as "It's a Gift" and "The Bank Dick" complement the Coens' cynicism perfectly. It's no wonder Kubrick, whose dark worldview perfectly aligned with the Coens, listed "The Bank Dick" as one of his 10 favorite films. There's not a whole lot of love of humanity in the Coens' work, and Fields and Kubrick also knew that there was no profit, artistic or otherwise, in giving a sucker an even break.

And that might be one of the problems.

Also in 1967, rock critic Robert Christgau wrote that Paul Simon "writes about that all-American subject, the Alienation of Modern Man, in just those words." As with all great criticism, that's rather unfair, but accurate, and something that comes to mind when the Coens get a little too remote and precise in yet another chilly exercise in craft over content.

Now, issues of craft and content are somewhat irrelevant when it comes to the second half of our double bill. This film has the courage of its conviction, using cannibalism not so much as a metaphor for the dark side of suburban consumerism, but as a metaphor for, well, cannibalism.

"Parents" is a much less heralded American-gothic nightmare from 1989, a coal-black comedy that makes the Coens' darkest views of America seem positively Disneyesque. Although "Parents" has been dismissed as minor-league David Lynch, it is a transgressional minor masterpiece as well, and blurs the line between the black and the comedy in a way that still astounds, beginning where that last apocalyptic reel of the Coens' "Barton Fink" left off.

Directed by Bob Balaban, "Parents" stars Randy Quaid and Mary Beth Hurt as the progenitors of an alienated child who has slightly more to worry about than a confiscated transistor radio.

Set in pretty much the same suburban petri dish of " A Serious Man," about 10 years earlier, "Parents" doesn't just dance around the horror of repressed American life. It lurches straight into a maelstrom of sex, violence, madness and frying kidneys, with some brilliant primary-colored art direction to boot. Perhaps the most convincing argument for vegetarianism ever put on celluloid, "Parents" makes "Food, Inc." look like an orientation video for a fry cook at KFC. They don't make 'em like "Parents" anymore, for probably some excellent reasons. Balaban's feature career never recovered from this release, though he did go on to direct scads of TV projects.

Our loss.

Unlike "A Serious Man," which dazzles with technique, filmmaking bravura and not a whole lot else, in "Parents" there's actually more than meets the eye, not less. William Cameron Menzies' "Invaders From Mars" is this film's only rival when it comes to evoking '50s paranoia as seen through the eyes of a child, and in this opus, there are no visible zippers on the monsters.

These monsters are much closer to home.

The plot of "Parents," such as it is, revolves around an only child, the wide-eyed witness to the shenanigans surrounding Quaid's job as an Agent of Orange for a company called Toxico. Quaid brings mysteriously wrapped packages of meat home nightly from the office's convenient morgue (don't ask), and serves them up in a "Calvin and Hobbes" fantasy of nightmarish dinners come to life -- exponentially multiplied.

And served blood-rare.

The child is imprisoned by both the text and subtext of his parents' bizarre dynamic, and his resulting strange behavior at school attracts the attention of one Miss Dew, played by the wonderful Sandy Dennis, a proto-earth mother social worker who learns a bit more about the parents than perhaps she bargained for.

Randy Quaid plays the traditional role of "Father Knows Best," if Dad were Jeffrey Dahmer. Pointing to his forehead, in one of the many spooky father-and-son chats that weave throughout the film's compressed 80 minutes, Quaid points out that the "real darkness is in here."

That would be an affirmative.

There has always been a vein of rich lunacy running just under the surface of both Quaid brothers. Dennis used that crazy to animate his brilliant portrayal of Jerry Lee Lewis, shocking those who thought he was just an all-American boy with "The Right Stuff," and Randy brought his crazy to his portrayal of another larger than life lunatic, Lyndon Baines Johnson, in a TV miniseries made a couple of years before "Parents."

Tragically, this "crazy" now seems to be eating Quaid from the inside out, and his current tabloid-haunted existence has taken that "art imitating life" thing just a little too far.

The rest of the family cast is terrific as well. Mary Beth Hurt, all tight and all control, brings a hysterical edge to the Perfect Mom, who shares a deep, dark secret from the world, and the family's 10-year-old son. Her pre-orgasmic ecstasy at Dad putting food on the table has to be seen to be appreciated, and one is reminded just how good Hurt can be when she brings her A game, even to B movies like this. After witnessing the haunted performance of Brian Madorsky, the viewer will not be surprised to learn that this was Madorsky's one and only film.

No actor could not go too much further than this, as the oceans of blood, real and imagined, in "Parents" make the elevator scene in "The Shining" look like one of Don Draper's staid Hilton commercials.

How a film like this could have gotten made, let alone marketed as a garden-variety horror film remains as much an enigma as the Body Procurement Services at the Toxico "Department of Human Testing."

But let's be clear. "Parents" is far from perfect. There is a fair amount of "Look, everybody, I'm a director, not an actor" wankery in many of the sequences. Even though the film's ending devolves into more traditional Grand Guignol horror country, those shocks quickly subside. The creepy, though, lingers on, in a way that many of the Coen brothers' lesser and even greater work does not.

As so often happens with the best B movies, "Parents" stays with you after a casual viewing, even though in this case, you dearly wish it wouldn't.

One last tiny thing.

Perhaps that Christgau quote has roused the rock historian within me, but one of the best running gags in " A Serious Man" involves harassing phone calls from a dedicated agent of a record club. Our put-upon hero is reminded he is way past due on a payment for Santana's "Abraxas" album, a fab waxing that was actually released in 1970, three years after the setting of "A Serious Man."

Just saying.

But then again, say what you will about the Coens, and people probably say way too much, they are nothing if not meticulous, and perhaps they are just playing another existential joke on cultural trainspotters like me, who look too hard for too much inside their work.

Maybe that is their most consistent joke.

Got another suburban-dread double bill for "A Serious Man"? "Welcome to the Dollhouse"? "Portnoy's Complaint"? The 1957 suburban fantasia "No Down Payment"? Get off that patio furniture and advise us!

Shares