For Aaron Swartz, the act of sharing was a "moral imperative." In his Guerilla Open Access Manifesto, released to the Web in July 2008, he specifically targeted the "world's entire scientific and cultural heritage," which he said "is increasingly being digitized and locked up by a handful of private corporations." Swartz called for those with access to such knowledge to make it available to others.

You get to feed at this banquet of knowledge while the rest of the world is locked out. But you need not -- indeed, morally, you cannot -- keep this privilege for yourselves. You have a duty to share it with the world. And you have: trading passwords with colleagues, filling download requests for friends ... Only those blinded by greed would refuse to let a friend make a copy.

In July 2011, Swartz was arrested on charges of illegally downloading 4.8 million documents from JSTOR, an online archive of scholarly articles. Facing a maximum possible prison sentence of 35 years and a fine of as much as a million dollars, Swartz killed himself Friday night, just two days after prosecutors rejected a plea bargain deal that would have allowed him to avoid jail time.

Previously, U.S. District Attorney Carmen Ortiz had sweepingly dismissed the notion that "morality" had a role in Swartz's actions: "Stealing is stealing, whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data or dollars.”

Strictly speaking, according to economic theory, Ortiz is wrong. There is a crucial difference between liberating documents from JSTOR and breaking into a car with a crowbar to steal someone's iPhone. This is the manifest difference between things and ideas. If I have an apple, and you take it and eat it, I don't have the apple anymore. But if I have an idea, and you take it, I still have the idea.

This fundamental attribute of knowledge is a fact that can't be argued away. Knowledge is just different. Knowledge can be infinitely shared and copied. In the age of digitization and computer networks, this fact can have negative consequences, as the publishing and music businesses have learned all too well over the past 15 years. But it also has positive consequences. The fact that there is no such thing as "scarcity" when applied to knowledge has enormous implications for how societies grow and prosper. The spread of the industrial revolution over the entire globe and the vast advances in human welfare over the last few hundred years can in large part be credited to this amazing fundamental attribute of knowledge: Ideas spread. Good ideas spread like wildfire -- unless they are constrained by artificial forces.

Indeed, there is an entire body of economic theory that argues that knowledge should be shared and copied, or at least, shared more easily and frictionlessly than is currently the case. Societies that share more information are better off -- there's more innovation, more technological and medical progress, faster economic growth, and more prosperity at all.

But when corporations are given too much power to lock up intellectual property with patents and copyright and friendly courts and bought-and-paid-for politicians, progress slows.

Notice, here, the implication of the words "too much." I suspect that Aaron Swartz was more of an absolutist than most people in his beliefs about the moral imperative of sharing, but the truth is, as a society, we are always engaged in a negotiation about where to draw the line between what should be shared and what shouldn't. How much power should corporations have to corral knowledge? Should copyright last forever, or for 50 years, or for as long as the Disney Corp. needs to keep Mickey Mouse under wraps? Should pharmaceutical companies be allowed to patent their drugs for eternity, or be forced to allow generic competition after a set period of time (thus lowering prices and increasing access). For many observers, even as we are willing to acknowledge that easy sharing and distribution has wrought havoc on writers and musicians, it seems fairly obvious that corporate influence over the political process with respect to intellectual property carries a real threat to slow down the spread of knowledge to the detriment of all.

Swartz saw that threat. Swartz devoted his life to combating that threat, to taking advantage of the essential capabilities of the Internet to make it easier for people to share knowledge. Swartz's methods could be extreme -- breaking into a closet, hacking into MIT's network and downloading 4.8 million documents were tactics that even some of his closest philosophical allies did not condone. But his target made sense. A significant proportion of the scholarly works in JSTOR were produced by academics working at taxpayer-supported institutions. You don't have to be an information-wants-to-be-free hacker to think that it is unconscionable that private corporations are allowed to profit off work that the public has paid for, but enjoys no legitimate access to.

Such practices are anathema to the fundamental purpose of the university -- which is to educate, and not to generate profit. The fact that university library budgets can no longer afford access to knowledge produced by universities is a travesty -- particularly in an era when the physical distribution costs of academic research are effectively zero.

JSTOR effectively admitted this by refusing to pursue charges against Swartz. And in one of the greatest ironies of Swartz's tragedy, just two days before he hung himself, JSTOR massively expanded its open access program.

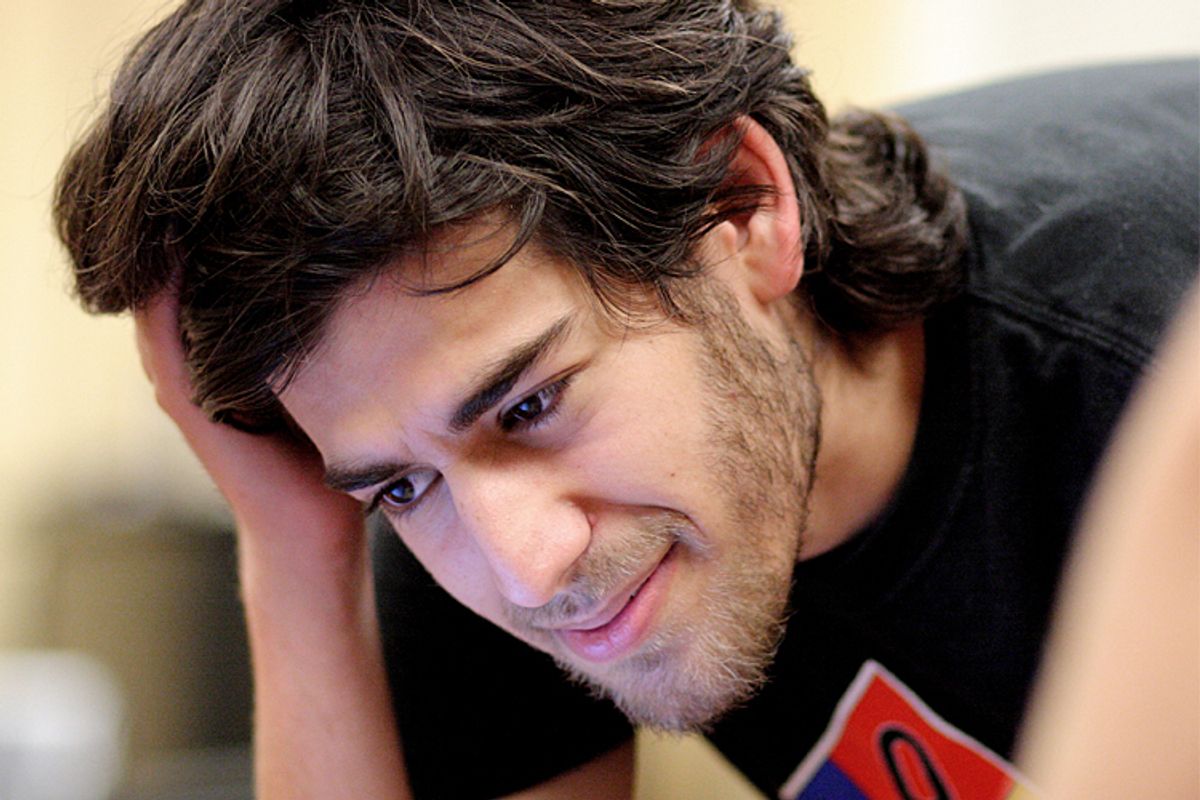

If you want to know why the Internet is grieving for Aaron Swartz, here's at least part of the answer. Few people understood as well as he did the Internet's potential for the betterment of society as a vehicle for spreading ideas. Few people showed more determination in writing code that would facilitate that process than he did. And few people paid a bigger price, at far too young an age, for pushing their idealism to the breaking point, than he did.

Shares