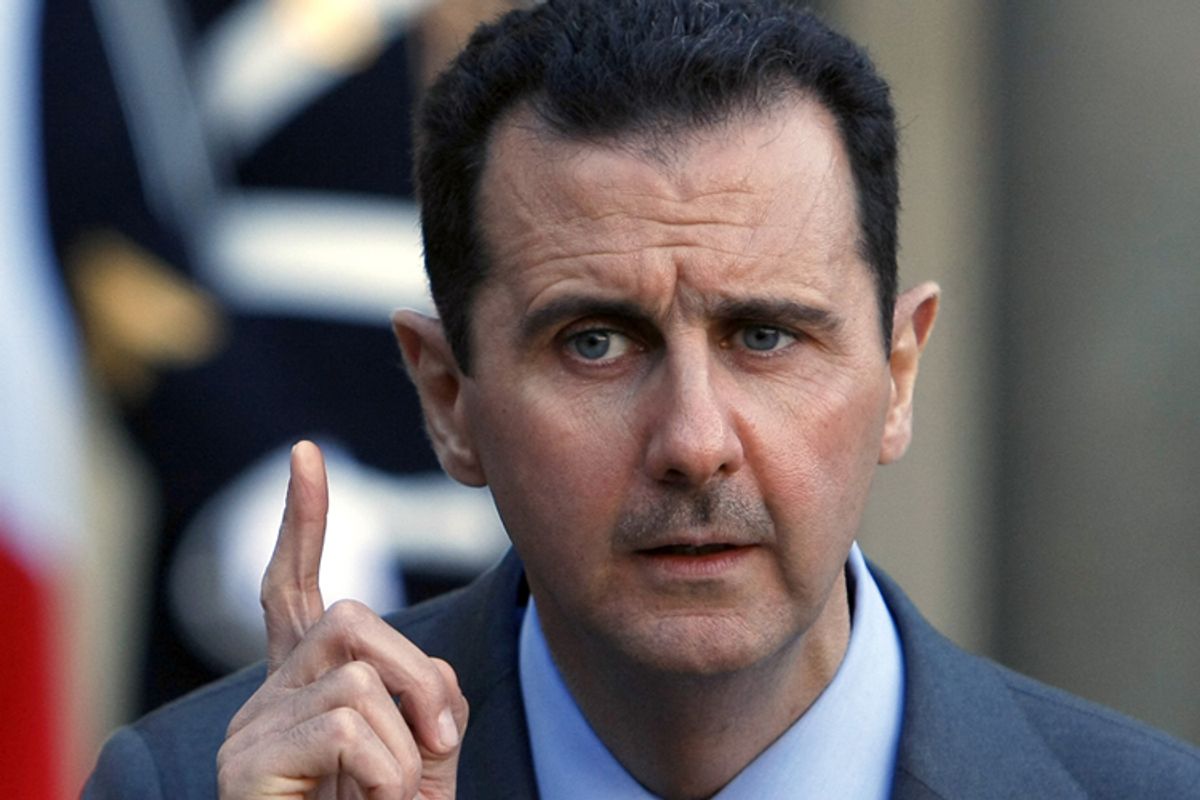

When presenting the case for military action against Assad's Syrian regime, Secretary of State John Kerry told a Senate hearing Tuesday that while a "boots on the ground" incursion was not desirable, it could not be precluded as a possibility.

The admission, made in response to questions from Sen. Robert Menendez, D-N.J., sat at odds with the administration's repeated vows a proposed Syria attack would take the shape of short, sharp missile strikes aimed at dissuading and disabling Assad from using chemical weapons again.

But, as antiwar advocates have pointed out, war is never so neat. A report by respected think tank RAND affirms as much.

“In spite of often casual rhetoric about ‘taking out’ Syria’s chemical weapon capability, the practical options for doing so have serious limitations, and attempting it could actually make things worse,” noted study authors Karl P. Mueller, Jeffrey Martini and Thomas Hamilton.

The RAND study stressed too that the risks of striking Syria over the use of chemical weapons (what Kerry moralized as "humanity's red line") could worsen the situation in the beleaguered region specifically in terms of chemical weapons usage:

Aside from the risk that bombing chemical weapons might cause chemical agents to be released or that attacking aircraft might be lost, the principal risk associated with such attacks is that gradually gnawing away at the Assad regime’s chemical weapon stockpiles would create a powerful “use-it-or-lose-it” incentive to relocate chemical munitions to places where they could not be bombed or, worse, employ them while it still had the opportunity to do so. In addition, attacks that damaged chemical weapon storage sites without destroying the weapons would increase the chances of unsecured chemical weapons falling into more-dangerous hands than those of the Syrian regime.

Shares