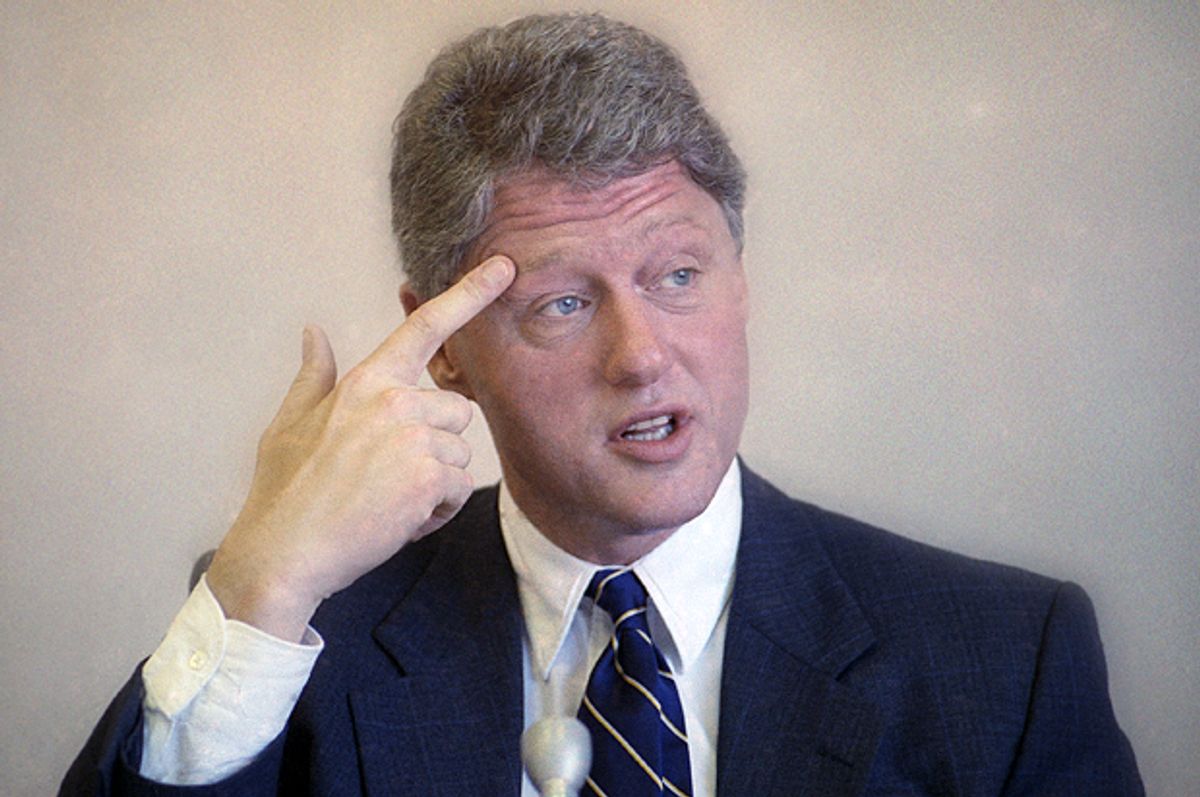

It was all the way back in 2010 that former President Bill Clinton said he regretted adopting "Don't Ask, Don't Tell," even as Senate Republicans were still blocking its repeal. "Do you ever regret it as a policy?" CBS News anchor Katie Couric asked him, and he responded, “Oh, yeah,” then added, "But keep in mind, I didn't choose this policy." He went on to say, “But the reason I accepted it was because I thought it was better than an absolute ban. And because I was promised it would be better than it was.”

Then, in March 2013, he wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post calling the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act—which he also signed—“incompatible with our Constitution,” and asked the Supreme Court to overturn it. “It was a very different time,” he explained.

Now, he’s done it again. In a speech to the NAACP national convention, Clinton very prominently echoed earlier statements of regret about contributing to indiscriminate mass incarceration with his signature crime bill, the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. “I signed a bill that made the problem worse and I want to admit it,” Clinton said. He did not disavow everything in the law, but increased incarceration was a central feature of it, and the fact that he admitted it made things worse was rightly seen as a major reversal.

In one sense, this is a very refreshing pattern of behavior, particularly when other presidents have not come anywhere close to acknowledging similar grievous errors in judgment. On the other hand, it reminds us that there’s a good deal more Clinton could apologize for—the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, which helped him get elected, or turning his back on DOJ civil rights division nominee Lani Guinier, or arm-twisting congressional Democrats for the passage of NAFTA. There's his signing the GOP version of welfare reform, after House Democrats had voted against it overwhelmingly and had expected Clinton to veto it for a third time. There’s a very good reason to return to reconsider those choices Bill Clinton made—if we want to chart a new direction, it helps to fully understand what’s thrown us off course in the past.

But before we do that, we shouldn’t forget just what a rarity Clinton’s admissions are. Clinton’s successor, George W. Bush, had plenty of huge mistakes he could have taken responsibility for, but instead has stayed silent about. The invasion of Iraq and his massive tax cuts, which wiped out the projected $5.6 trillion, 10-year surplus Clinton left us with, come readily to mind. On both counts, if Bush were to come clean about his mistakes as Clinton has done, he could go a long way toward making it much easier for us to find successful pathways for our nation's future. Failing to heed advance warnings about 9/11 or New Orlean's vulnerability would also make good apology material, if Bush were so inclined. But, of course, we know that he is not. Ignoring the repeated pre-911 warnings about Al Qaeda was simply inexcusable; there’s nothing to discuss. Likewise, video and transcripts obtained by AP show Bush and his team utterly disconnected from the disaster of Katrina bearing down on New Orleans. But these were more in the realm of failures to execute what should have been well-laid plans.

The Iraq War and his tax cuts fall squarely in center of the policy realm, and both actions not only turned out disastrously, they continue to be staunchly defended by people who have failed to recognize, much less analyze and learn from how they failed. The Iraq War diverted attention from the small but lucky band of terrorists—criminals, not warriors—responsible for 9/11, and involved us in a totally unrelated conflict, which nonetheless ended up creating the kind of state terrorist entity Bush had erroneously believed Iraq to be. The fact that ISIL did not emerge in its current form until after Bush left office does not erase the fact that his war policy made its development possible, if not inevitable, along with a broader range of institutionalized carelessness.

So let’s give Clinton his due. To err may be human, but to admit major policy mistakes as president is something most humans would find extremely difficult, regardless of how obvious, how glaring the mistakes might be. For that reason alone, we ought to be grateful for Clinton’s honesty and candor—even, in a sense, his courage.

And yet, he still has so much more he could—and should—apologize for. And, as with Bush, it's not just about Clinton—it's about all of us learning something, and hopefully doing better as a result. Presidents act on behalf of us all; we all have something to learn from their mistakes. The list I cited earlier is by no means exhaustive, but it is useful to consider.

Because it’s the most painful, I think we should start with the case of Ricky Ray Rector, whose execution Clinton made part of his campaign for president. Rector was no angel. He was a convicted double murderer. In 1981, he killed one man for refusing a friend entry to a night club, and he killed the second—a long-time friend, who was a police officer—when he came at Rector’s request to arrest him. But here’s the twist: Rector also tried to kill himself, immediately after the second murder. Instead, he gave himself a partial lobotomy, leaving himself deeply incapacitated with an IQ of about 70. It left him a completely different, utterly helpless and dependent man.

There had been an earlier case, Ford v. Wainwright, in 1986, in which the Supreme Court held it was unconstitutional to execute the insane. While Rector’s initial lawyers had not been very able, he eventually was represented by lawyers who appealed his case to the Supreme Court, arguing that the same principle should apply to the mentally incompetent as well. The Supreme Court refused to hear the case, but Thurgood Marshall—who wrote the decision in Ford v. Wainwright—took the unusual step of filing a dissent from that refusal, in which he wrote:

The issue in this case is not only unsettled, but is also recurring and important. The stark realities are that many death row inmates were afflicted with serious mental impairments before they committed their crimes and that many more develop such impairments during the excruciating interval between sentencing and execution…. Unavoidably, then, the question whether such persons can be put to death once the deterioration of their faculties has rendered them unable even to appeal to the law or the compassion of the society that has condemned them is central to the administration of the death penalty in this Nation. I would therefore grant the petition for certiorari in order to resolve now the questions left unanswered by our decision in Ford v. Wainwright.

In 2008, after Bill Clinton’s intemperate response to Obama winning the South Carolina primary shocked many in media, Chris Kromm, of the Institute for Southern Studies, looked back at how Ricky Ray Rector’s fate intersected with Bill Clinton in that campaign--one in which no Democrat wanted to face a "Willie Horton ad" like the one that helped destroy Michael Dukakis in 1988:

It was almost exactly this time of year 16 years ago that then-Gov. Bill Clinton, eager to break away from a tight pack of 1992 Democratic primary hopefuls, decided crime would be one his big-ticket issues. Democrats should "no longer feel guilty about protecting the innocent," he would proclaim from the campaign trail.

How did candidate Clinton choose to show he was "tough on crime?" By flying down to Arkansas, mid-campaign, to personally preside over the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a mentally retarded African-American man.

It was only the third death sentence carried out in Arkansas since 1973, and Clinton made a point of being on hand for the TV crews when Rector was killed by lethal injection on January 24, 1992.

In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled that executing persons who are mentally retarded is "cruel and unusual punishment." And in the court of public opinion, many African-Americans judged that Clinton--far from being a "black president"--was in reality another white president who was all too willing to use race when it suited him.

Kromm went on to quote Margaret Kimberley at The Black Commentator:

[R]icky Ray Rector became world famous upon his execution in 1992. Then Governor Bill Clinton left the campaign trail in January of that year to sign the warrant for Rector's execution. Rector's mental capacity was such that when taken from his cell as a "dead man walking" he told a guard to save his pie. He thought he would return to finish his dessert.

I try to remember this story when I am told that all Black people love Bill Clinton or that he should be considered the first Black president. Clinton wasn't Black when Rector needed him. He was just another politician who didn't want to be labeled soft on crime.

The truth is that Bill Clinton has a complicated history of racial relations, and even some black politicians in his shoes would have done exactly the same thing. But if moving forward wholeheartedly requires us to acknowledge past errors, then Ricky Ray Rector’s execution is one more thing that Clinton should publicly regret.

The next year—his first year as president—Bill Clinton had a rocky relationship with black women when he backed out of two high-profile nominations. The first was Johnnetta Cole, the first black female president of Spelman College, who headed Clinton’s transition team for education, labor, the arts and humanities, and was slated to be selected as Secretary of Education. Her nomination was squelched after the Jewish Daily Forward reported she'd been a member of the national committee of the Venceremos Brigade, which the always-reliable FBI said was connected to Cuba's intelligence agencies. Nothing further needed to be said: guilt by association was automatically assumed.

The attack against Lani Guinier was far more extensive, protracted, and baseless. Guinier was a former staff attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, who had moved from being one of their top attorneys, heading their Voting Rights project, to proving herself a top-flight academic, at the University of Pennsylvania, with a series of sweeping, but well-grounded and sophisticated law review articles (most collected in her first book, "Tyranny of the Majority: Fundamental Fairness in Representative Democracy"), in which she argued for a need to rethink approaches to voting rights law, to avoid what she identified as a number of blind alleys. At the time, Guinier was only the second person ever appointed to head the DOJ's Civil Rights Division who actually had a background in the relevant law—both as a litigator and an academic. Yet she was shamelessly and ridiculously attacked as a “quota queen” (a blatant echo of the “welfare queen” slur), when perhaps the foremost thrust of her argument was the exact opposite—a rejection of drawing districts to ensure the election of a maximum number of black elected officials. Instead, she argued the purpose of democracy was to empower the maximum number of voters to elect candidates of their own choosing, regardless of race.

Guinier argued that multi-member districts provided an alternative that could promote an environment in which cross-racial politics could more readily flourish. (Republicans at the time were already starting to exploit the weakness of candidate quota systems, packing minority voters into a handful of Southern districts—most notoriously in North Carolina—in order to deprive white Democratic politicians of black electoral support.) Guinier gave her own account of the ordeal she was put through in her 1998 book, "Lift Every Voice: Turning a Civil Rights Setback Into a New Vision of Social Justice," in which her focus is on stressing the lessons for organizing that social justice advocates needed to learn. However, it’s also clear that Clinton and his team somehow never recognized the take-no-prisoners mindset of their congressional opponents, never even began to craft an effective response, and worst of all, never even read Guinier’s work, so they had no basis on which to do anything but knee-jerk react to the accusations of others.

In the end, Bill Clinton spent half an hour or so reading through some of what Guinier had written—but only after he’d already decided to abandon her. Even so, it was far too little time to absorb the depth of the arguments she was engaged with. It’s surely true that Bill Clinton is a quick study—but he has rarely been required to study something as deeply challenging as the areas that Guinier explored. His failure to give her the hearing her ideas deserved has impoverished all of us, while giving encouragement to those who have dramatically intensified their attacks on voting rights in the decades since then. There’s a lot there for him to apologize for, not so much about a personal offense as it is about lost opportunities to build a much more robust democratic culture.

Both Cole and Guinier have continued in highly successful careers. Cole continued to head Spelman through 1997, and was president of Bennett College from 2002 to 2007. Since 2009, she’s been Director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African Art, located in Washington, D.C. Guinier moved to Harvard Law in 1998, where she’s taught ever since, though with various high-profile guest appointments. She's written five books and scores of law review articles. But neither of them has been fully appreciated and integrated into a national public discourse that generally operates substantially below their level of intelligence. Their loss has been the nation's loss as well.

I also listed two significant pieces of legislation that Clinton ought to consider apologizing for. The first is NAFTA (which he championed); the second is welfare reform, which he advocated for in a different form, but ended up signing the GOP version of anyway. Both pieces of legislation are deeply flawed in and of themselves, but they’re even more flawed as models that continue to be built on.

NAFTA was not only a policy disaster—more on that in just a minute—it was a political disaster as well. In the course of advocating for NAFTA, Clinton and Gore alienated and humiliated Ross Perot, creating an opening for the GOP to woo him and his supporters, which they fully took advantage of, particularly in the crafting of the 1994 “Contract with America.” The story of how this came about, and how significant it was in shaping long-term political shifts, is told by Ronald B. Rapoport and Walter J. Stone in their book, "Three's a Crowd: The Dynamic of Third Parties, Ross Perot, and Republican Resurgence," which I’ve written about before here at Salon as well as at Open Left.

It’s amazing that NAFTA enjoys so much more support from the GOP, yet it’s the Democratic Party that’s paid such a heavy price for much more narrow, yet ultimately crucial support. While much of what Clinton has done was sold on the basis of political necessity, it’s utterly impossible to see how NAFTA passes that test. With only two brief two-year terms, the Democrats had controlled the House of Representatives from 1931 through 1994. Republicans have controlled it for all but four years since then, even when Democrats have won more popular votes at the polls.

On the policy side, Robert E. Scott from the Economic Policy Institute explained NAFTA’s impact in December 2013:

Former President Bill Clinton claimed that NAFTA would create an “export boom to Mexico” that would create 200,000 jobs in two years and a million jobs in five years, “many more jobs than will be lost” due to rising imports. The economic logic behind his argument was clear: Trade creates new jobs in exporting industries and destroys jobs when imports replace the output of domestic firms. Fast forward 20 years and it’s clear that things didn’t work out as Clinton promised. NAFTA led to a flood of outsourcing and foreign direct investment in Mexico. U.S. imports from Mexico grew much more rapidly than exports, leading to growing trade deficits, as shown in the Figure. Jobs making cars, electronics, and apparel and other goods moved to Mexico, and job losses piled up in the United States, especially in the Midwest where those products used to be made. By 2010, trade deficits with Mexico had eliminated 682,900 good U.S. jobs, most (60.8 percent) in manufacturing.

The figure referred to shows that U.S./Mexico trade was essentially in balance when NAFTA was passed, while the U.S. trade deficit with Mexico has grown ever since, topping $100 billion in 2012. Perhaps if Bill Clinton had been willing to apologize for NAFTA, we would not have just recently had President Obama arm-twisting Democrats to get fast-track authority for even more such trade deals to come.

Last on my short list of things for Clinton to apologize for is welfare reform. In 2010, I wrote a six-part series, “The Myth that Conservative Welfare Worked.” While the conservative-dominated end product was my primary concern, I did pay attention to what Clinton was trying to accomplish, particularly in Part 1, where I drew extensively on Diana Zuckerman's article, "Welfare Reform in America: A Clash of Politics and Research," published in the Journal of Social Issues, Winter 2000, to provide a detailed account of how welfare reform unfolded. Clinton began work with a Democratic Congress, and he came in with a relatively clearly defined agenda, which was relatively—though not entirely—non-punitive, aimed primarily at trying to adjust to changed social circumstances. However, it was promoted electorally with phrases that could easily be turned against its more thoughtful requirements, particularly once Republicans won power in the '94 elections. As Zuckerman writes:

Ellwood [in an article in the American Prospect] also speculates that the President's promise to "end welfare as we know it" was a potent sound bite but did not address the concerns of many Democrats about whether the new system would be better than the old. Ellwood believes that the phrase "2 years and you're off" was even more destructive, because it implied no help at all after 2 years, which he says is "never what was intended." I agree that these were problems, and in addition, the tension and lack of trust between the congressional Democrats and the Clinton administration contributed to the view of many Democrats that the Clinton welfare plan was too controversial and would make them politically vulnerable.

A big-picture gloss on all this is that Clinton’s legislative agenda was crafted in terms of his own individual political calculus, in relative isolation from the rest of the Democratic Party. He used slogans that worked for him running for president, but gave relatively little thought to how they might create difficulties for others—or even for himself, once Republicans took power, and adopted that same (or similar) language for their own purposes. As I noted a bit later, “once the GOP took over Congress in 1995, they took charge of writing the law, and Democratic concerns to craft a program that helped the poor were largely swept aside.”

Conservatives were basing their arguments on Charles Murray's factually challenged book "Losing Ground," which essentially argued that poor people’s bad morals were to blame, whereas progressives relied on arguments by researchers like William Julius Wilson, who looked to economic changes like the decline in well-paying manufacturing jobs and their replacement with lower-paying service jobs as disastrous for inner-city black men and their chances of a normal productive work and family life. I went on to note:

It's clearly much easier to lecture and punish welfare mothers than it is to actively restructure an economy to provide more opportunity for those on the bottom to work their ways upward. The very ease of the conservative prescription was part of its selling point. The fact that it didn't address the basic underlying problem was, politically, a feature, not a bug.

Even before he adopted the legislative strategy of “triangulation,” Clinton had rhetorically done the same thing, and his use of language meant to appeal to conservatives ended up being used by them to pressure him into signing their law, which—despite his misgivings—he ended up doing. One reason why was that he had some additional tricks up his sleeve, including the expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the rising job market of the booming economy he presided over. “But this said nothing about what might happen when the economy turned sour again,” I noted. This obviously came to pass with the Great Recession, as noted by Think Progress in 2012 and 2013.

It was never my intention in drawing up this list to simply pile on to Bill Clinton. As I said before, I think it's a good and far too rare thing for a politician to admit to their mistakes. It's not just about Clinton, but about all of us learning something, and hopefully doing better as a result.

So what I do want to do now is try to draw some larger lessons. And the lessons, I think, are fairly simple ones, once you come to see them properly.

There are two common threads that run through almost all the things that Clinton regrets—or should regret—and common sense says that these are things that need to change. The first is that Clinton was trying to mediate between his liberal base and its ideals on the one hand (still forming, for many, in the realm of gay rights in the 1990s) and more conservative voters, typical of those he dealt with in Arkansas, on the other. This is a formula that many Democrats have long taken for granted, but the regret—even embarrassment—Clinton now feels is an indication that there's something deeply wrong with it.

Underlying this formula is the assumption that America is basically a center-right nation. You can move in a progressive direction, but to do so you must carefully pick your spots. As indicated in my recent interview with political scientist Matt Grossman, there is a lot of evidence that points in this direction, but only in the sense of broadly-stated abstract preferences. When you get down into specific, programmatic details, the nation suddenly starts to look a whole lot more progressive. This is a large part of the reason why Bernie Sanders has such a strong appeal, and has been able to gain broad cross-ideological support in Vermont over the years.

This is not a secret unknown to Bill Clinton, either. In January 1998, the Lewinsky scandal broke, and the political buzz was intense. There was even talk about Clinton resigning within days or weeks. But Clinton kept his head down, stayed focused and delivered an extremely detailed, but extremely focused State of the Union address. A major point was that the federal government would finally be running a surplus, and that the surplus should be devoted entirely to saving Social Security, but Clinton touched on a great many other subjects as well, in a detail-packed speech that lasted over an hour and 15 minutes. The results were impressive. CNN found that those who watched the speech approved of it by 84-16%, and the percent saying they were confident in his ability to carry out his duties rose from 66% to 78%.

The lesson here is simple: It's better for Democrats to stay focused on specific action items and urge folks to work together to get things done, rather than talk in generalities that tend to give the advantage to Republicans. You can't actually do things in general, anyway. When push comes to shove, you've got to do something specific, so put your focus there, and be proud of it—and enthusiastic, too!

The second thread running through most of these examples is that Clinton was caught up in trying to do what was best for him as an individual politician. It would be a big mistake to think of this as a personal failing on his part. Quite the contrary, it's been a systemic fact of life in American politics for a while now. In his 2001 book, "Democracy Heading South: National Politics in the Shadow of Dixie," Augustus B. Cochran III argued that U.S. politics at the turn of the century closely resembled Southern politics 50 years earlier as described in V.O. Key's classic work, "Southern Politics in State and Nation," and this sort of individual focus was one aspect of what he was talking about.

Cochran argued that the structures were different, but the functions were the same, like the relationship between gills and lungs. “Key argued that because Southern politics lacked strong, responsive parties, was based on a narrow electorate, and was designed to perpetuate white supremacy, Southern electoral institutions lacked the coherence, continuity, and accountability that could make Southern politics rational and democratic,” Cochran noted. And he argued that just as these factors hobbled the South's ability to become an industrial democracy, a parallel set of constraints were crippling America's ability to become a postindustrial democracy. “Specifically, the maladies of the Solid South included elections that ignored or blurred issues; weak, elitist and even demagogic leaders; a proclivity to avoid problems and coast along with the status quo; rampant corruption and policymaking by deals; voters who were confused and apathetic; an appallingly narrow electoral base, including low turnout among even those lucky enough to be enfranchised; a resulting tilt toward the elites, while the have-not majority got taken for a ride.” Politics was also widely seen as a form of entertainment—show business—and political actors tended to be individual aspirants, rather than team players, since a one-party system readily devolved into cliques or chaos, often with slippery, shifting alliances.

As money and media have become more important, and party discipline and ideological coherence have eroded, national politics today has become more like the Southern politics of old, Cochran argued. And that seems like a very fitting description of how Democratic Party politics in particular devolved throughout the 1980s and '90s. Bill Clinton may have been the most dominant Democratic politician of that era—the only Democrat elected president between Jimmy Carter and Barack Obama. But to the extent that he acted like a cowboy sometimes, and that go-it-alone tendency got him into trouble down the road, he was not exhibiting a personal failing so much as he was showing us a problem we all shared.

It may be easier to see than it is to remedy. But seeing clearly is a very good first step. And admitting you have a problem is absolutely necessary before you're ready to start work on fixing it. So Bill Clinton admitting his past mistakes may well be a much bigger deal than most of us yet realize. It could be an invitation to something we all share a stake in—as well as a responsibility for.

Shares