Is your humanity purely based on the quid pro quo system? Early on in her career as a minister, Lynn Casteel Harper was introduced to the patients on a dementia unit. She was then informed she wouldn't have to deal with them much, because they wouldn't remember her anyway. The implication struck her — that it's not worthwhile to do anything for someone if that action couldn't be reflected back to you somehow. It set her on a course of examining how we talk about people living with dementia, and what that implies for both their care and our culture.

We live in a country that claims to value human life — until that human life is deemed unprofitable. Last month, Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick suggested that older people ought to be "willing to take a chance on your survival in exchange for keeping the America that all America loves," while The Federalist mused, "It seems harsh to ask whether the nation might be better off letting a few hundred thousand people die. . . . Yet honestly facing reality is not callous."

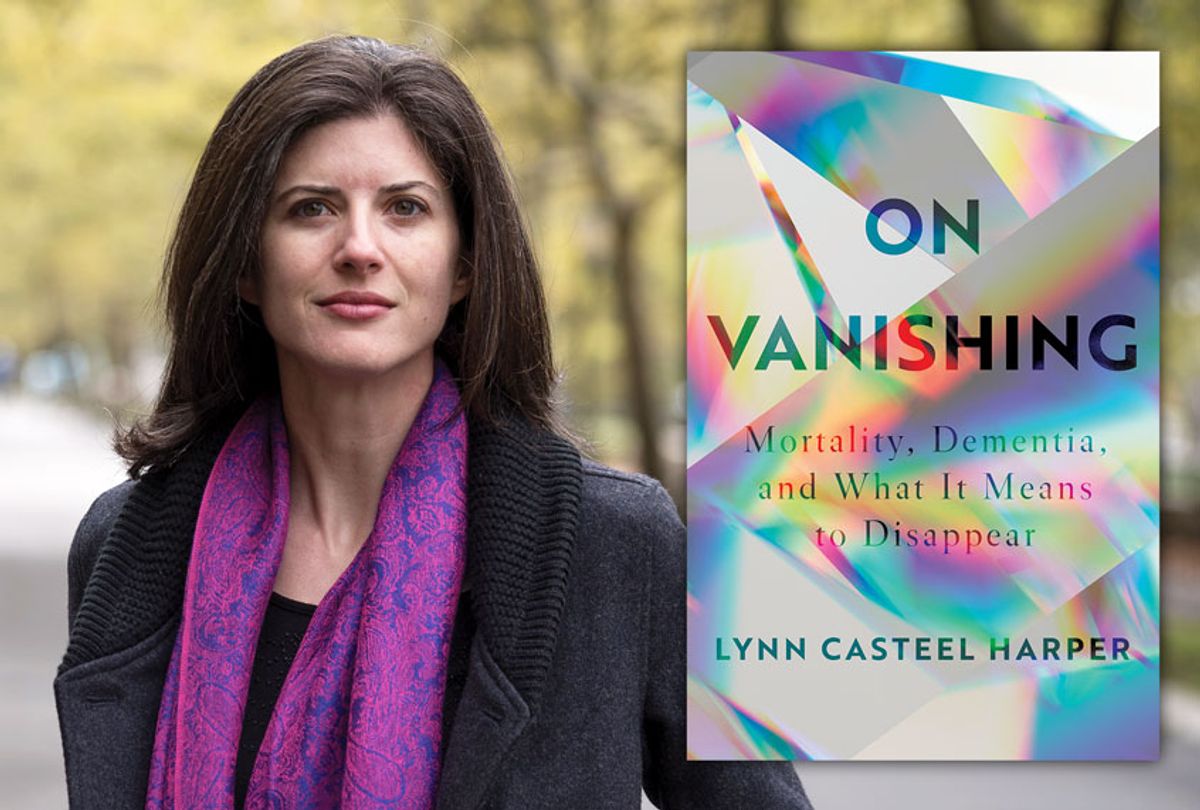

What is the value, then, of a person who is elderly, whose memory is declining? In "On Vanishing: Mortality, Dementia, and What It Means to Disappear," Casteel Harper explores her own family history and our fraught linguistic relationship with the disorder, and makes a compelling case for a profound shift in our understanding of it. Salon talked to her recently via phone about the book, and how she's seeing the ethical questions it raises playing out now right before our eyes.

This book must feel even more relevant today than when you turned it into your publisher.

It's almost surreal. It almost feels like a little too pointed, a book on what it means to disappear when everything from sporting events to jobs to actual lives are disappearing.

You wrote, "No disaster, no war, flooding, famine, initiate the everyday expulsion of elders and modern America. The processes are slower, more covert and less openly violent than other forms of banishment. Perhaps that accounts for why we have been so slow to name this injustice." I got chills reading that.

And here we are, in this moment where nursing homes just being ravaged by COVID-19. It's almost like there is an open violence to it, through a process of this vanishing for so many decades. Now we are seeing dozens of lives lost a week in certain nursing homes.

It's clear that you have so much personal investment in this. Like you, I think about my own genetics and what the implications of that are. But what made you decide to write a book that speaks to your experience, to what we think about dementia and to the history of our conversation around it?

It started for me, really coming to know people with dementia on the dementia unit as a chaplain. At the same time, my family experiencing it up close with my grandfather and really knowing people by their names, by their histories, their preferences, their desires, and not a mass blur of disability. Coming close was really key. My writer's sensibilities come up when something doesn't match with the larger culture. The message I was hearing otherwise is that these people are gone, vanished. I talk about my first day in the nursing home, my guide saying, "You won't spend much time here on the dementia unit," the implication being, these people don't really need you because they won't remember you.

I was expected to sort of withdraw my presence from them because they had "disappeared," quote unquote, to their disease. Something wasn't squaring between my experiences of my grandfather and people in the dementia unit and this larger cultural narrative, that people are gone or vanished or disappeared or shells. As a writer, you're always thinking about those dissonances and language and what you're experiencing. Add to that as a minister in a Christian tradition, wedded to social justice, there's always that question of who's being left out and why. It usually doesn't have something to do with what they're doing wrong, but how the dominant culture is framing them.

Especially in terms of reciprocity. That is so very clearly our understanding of the market value of humans.

Our ageism is linked to the economy. We are seeing literally elected officials talking about who is expendable. We see it outright, people talking about it openly. It's almost as if ageism is the last -ism that is just okay. Without repercussion, people talk about it, even talking that there aren't that many years being lost to COVID-19, even though there are a lot of lives. I don't know how to account for the value of someone I loved, one year of their life.

You talk eloquently about these preconceived notions we have about this very specific population, the elderly and people who have dementia. Even as someone who has seen it up close, I didn't really think about the words that we use and the language around it. You chose a very specific word for the title of the book. You talk about the images that we have right now about disappearance and about darkness. Why do you feel that that is not a good way to frame this?

Language is not just language. Language creates our reality. If we're imagining people as disappearing or disappeared, as vanishing in the most essential part of who they are, then our treatment will follow that. We see that people with dementia suffer neglect and abuse at a much higher rate than their peers. One in three people with dementia report losing friends. It really matters how we choose to speak about people. No one wants to be — I don't want to be — defined by my deficits, by my losses. Why would we do that for someone else? Why would we define someone by something that they don't have? To me, it's the equivalent of like asking someone with the bum shoulder to lift something. It's cruel. Why would we, if people have trouble thinking, require them to remember something in order to value their full humanity?

The way that you put it is, we need to be reminded that people with dementia are still human. So much of the imagery is that you become less of a person. And if someone's not going to remember me, then why would I interact with them?

Right. Like we go to those places to, in some ways, help ourselves. I always think about my relationships with people with dementia as a way to humanize myself. It's not just like a nice thing I do for these sick people, but it's actually a way to be more fully human in myself. To embrace those parts of myself that are strange and sometimes confused. And for someone to embrace me when I don't have it all together.

There are so many questions around, "At what point are you not a person?" What is that point where you are worthy of attention, worthy of life? And who gets to make those judgment calls? You really explained this very well, that even in a good healthcare system, even in a situation where someone is being well taken care of through no overt malice, this depersonalization occurs.

I'll be the first one to say that caregivers, family caregivers, professional care workers, are often just so incredible, are incredibly creative and intelligent. I think in our culture we lift up intelligence looking a certain way, as this kind of self-sufficient, Elon Musk kind of thing. These carers on the frontline are so intelligent in the way they're able to relate and communicate, and their capacity for compassion. I want to be mindful that when I'm critiquing the care of people with dementia, I want to always go back to systems and larger culture. It's not about guilting individual caregivers.

So much of what you write about it is in that metaphor of the Land of the Sick.

I think of Auguste D., the first person identified with the diagnosis of Alzheimer's. They talk about her being in an isolation room and then coming out to get probed by the doctor. And this idea of human subject, almost like human object for observation.

I loved in the book when you talk about the facility where staff and residents call each other "friends," and how powerful that is. This book is about this condition, but it's also so deeply about semantics and about the power of language. We have seen so clearly over the past few years the way that words can be weaponized.

And the way that they shape how we see ourselves and how we see others. I've learned this from dementia activists, people with the diagnosis who are advocating for different language and for better policies. I really learned from them, don't call us dementia sufferers. I actually use the word "sufferer" earlier in the book and kind of move away from it. They are people living with dementia.

Those things are not inconsequential, because then they change the public thought. When we talk about someone vanishing, the darkness coming in, that is scary language. It is language that makes people disappear even though they are still living, breathing, feeling and thinking humans. And it begs the question, who is disappearing from whom? Are they disappearing? Or are we disappearing?

It's been interesting the past several weeks seeing some people in both politics and in punditry try to figure out who bears blame for becoming sick with this virus. Is it because of what they ate? Is it because of what country they come from? Is it because, well, they were old and weak and had preexisting conditions?

In other words, how can we dismiss this and make this not about us? It's sort of like we can externalize our fear and our sense of helplessness that we feel and make it someone else's problem. So the fear that we feel about dementia, that cognitive loss about our own sense of limitation, rather than really working with that fear, we foist it onto others and "They're disappearing, they're no longer here, they're gone. They don't know anything. And so I don't have to take responsibility for my own shadow side, my own dread of illness or mortality." I think that's so damaging, and really leads us to a much harsher world where it's, Land of Sick, Land of Well. "Those people gave us a virus, and they're to blame." I think a gentler world is possible.

As someone who wrote this book about this extremely vulnerable population, what have you been experiencing the past few weeks? What have you been observing in your own community?

I am the minister of older adults at a fairly large church in New York City, but I decamped to Maine for now. I'm in touch by phone, email, good old letter writing, with older adults in New York city, especially in Harlem, upper Manhattan. It's a crazy feeling of holding my breath at each call. Are they going to be okay? How's their building, how are they, how are their families? We are seeing cases of the virus in our community, and everyone is starting to know someone. Thankfully, our older adults right now are for the most part doing well, getting what they need, sheltering in place.

Ironically, elders are at a risk of isolation. We know that. And they're saying, "I know how to do this. I've been doing this." In some ways a sheltering in place might be a little easier for them than for others who are used to just always being on the go or always having friends over. That's been a surprise to me in some ways, and a lovely one. But there's a lot of sadness, because it feels like the disappearance is going to be painfully literal, and I brace for impact. There's going to be so much complicated grief on the other side of this, and I'm just so grateful that our community of older adults are predispositioned to care for one another. They're calling each other. They're supporting one another. So I have been simultaneously inspired and overwhelmed by the humanity of the older adults. At the same time, like I say, I feel like every day I just brace.

We've spent the past several weeks just with our heads between our knees. Crisis makes you feel so moved and so appreciative of the beauty and the tenderness and the generosity of your fellow humans in ways that you may not ever experience in your life again. Yet it is also devastating.

And I would say I have a fair bit of anger for those who want to prematurely open the economy. I think, do you not see these precious older adults? Do you not see these lives as inherently beautiful, and worthwhile? I feel angry and sad for the world that doesn't allow someone to see that.

It's genuinely shocking to me when public figures are just outright saying that this is the collateral damage. That you should be willing to sacrifice yourself. And those who are being asked to sacrifice are not the strongest and the bravest, but the most vulnerable and the most marginalized.

So you can go to a Yankees game.

At this point, what is giving you hope and what is something that you hope we can do as a society moving forward?

I am given hope by the people who are just so creative and loving and community-minded, caring for the most vulnerable in this moment. Being very intentional about reaching out. I can't tell you how many people at the church have reached out. "How are our older adults? How can I help?" That gives me hope.

I guess my greatest hope is that only other side this pandemic can be a portal that we walked through to create a more compassionate setup for our frail, older adults, which I think will be then a gentler setup for all of us. One that doesn't rely on mass institutionalization, that allows people to live in their communities — well-supported communities that are well-educated about dementia. That there's intergenerational connection, and the resources to allow that to happen. That some of the fear is gone.

Shares