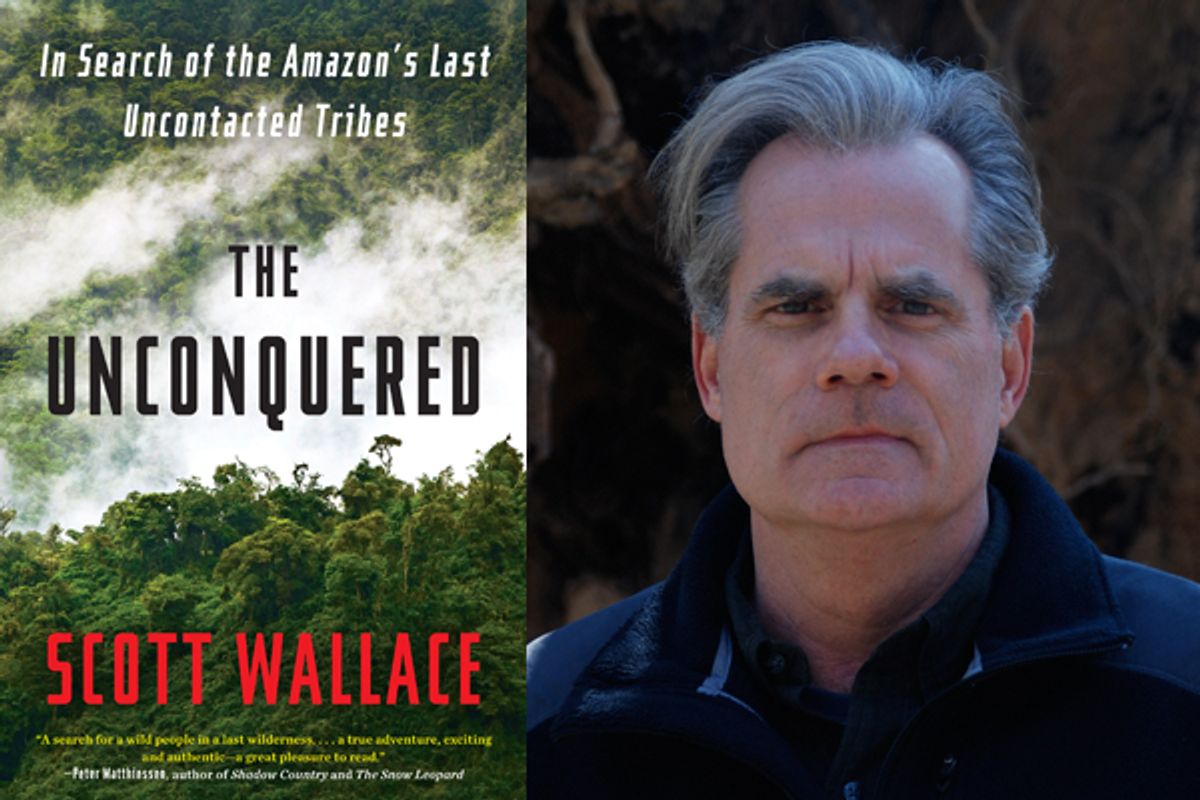

The world Scott Wallace describes in his new book, "The Unconquered: In Search of the Amazon's Last Uncontacted Tribes," is sometimes startlingly novelistic.

Sydney Possuelo, the activist whose jungle expedition Wallace joins at the request of a National Geographic editor, is a character in more than one sense of the word. When Wallace meets Possuelo on the Amazon, the expedition leader is head of the Brazilian National Indian Foundation (FUNAI)'s Department of Isolated Indians, a unit dedicated to the protection of the most primitive Amazonian tribesmen. If FUNAI officials do their job, these people will remain blissfully ignorant that they are being "protected" at all.

Possuelo leads his men past oddly-named towns ("Contraband"), around dangerous tribes (e.g. the "Head-Bashers") and through virgin jungle land, deep into a reservation -- Brazil's Javari Valley -- that is off-limits to all but the indigenous people for whom it has been set aside. His goal? To locate a previously uncontacted tribe known simply as the "Arrow People" -- but not to bother, disturb or even come face-to-face with any of its members.

In a phone interview, Wallace answered some of my questions about his experience; an edited transcript of our conversation is below. Check out the accompanying slide show for a further glimpse of his Amazonian adventure.

I’d like to start with a few terminology questions. The subtitle of your book is “In Search of the Amazon's Last Uncontacted Tribes.” In this context, what exactly does “uncontacted” mean? As far as I understand it, the tribes you’re talking about have all come into some sort of contact with other humans before. At one point in the book, you mention the term "resistant to contact" -- is that more accurate?

That’s a really interesting question. And yes, “resistant to contact” -- you’ve kind of hit the nail on the head there.

The contact that these groups have sustained has always been of a violent nature. So the only real dialogue that’s taken place with the outside world is one of flying bullets in one direction and flying arrows in the other. These people do have an awareness of the outside world, but they have no idea -- they could have no idea whatsoever -- of just how enormous the global community is. They would probably tend to see us as a tribe that occupies some other riverbanks. For the most part, their knowledge of the outside world is extremely limited.

What they do know of it is that it’s a dangerous place -- that it brings disease and violence and represents for them a mortal threat in some instances. The groups that we’re talking about know what firearms are; they’ve been shot at, they know that these weapons are dangerous. They know the white man is dangerous, and they are familiar with the fact that white men and women also possess these magical goods that are made from steel. You’ll often see evidence that they are in possession of at least a couple of steel tools -- an ax perhaps, or a couple of machetes -- and often the blades are quite dull. They recognize the value of steel, and they will go to great lengths to try to obtain it.

I’m also curious about your choice of the word “Indian.” You use it throughout the book, and it seems to be used officially in the Brazilian bureaucracy. Is there any complication with the use of that term? Is it just a colonialism that's seeped into normal vocabulary?

Perhaps in a way. It’s almost like we just use it for lack of a better word. We do use “indigenous” also; I kind of used the terms interchangeably in the book, with the knowledge that “Indian” is a colonial term, but one that we can’t really shake. To an increasing degree, it’s a word that indigenous people themselves have embraced with some pride. So I don’t have that much of a problem using it.

Going back to your “uncontacted” question, another really key issue is the transmission of microbes -- germs. For the most part, these societies have not sustained the kind of contact that makes them immune to the diseases we carry. They are still considered “virgin soil” populations, who do not have immunity to Western-borne diseases.

Let’s talk about Sydney Possuelo, the man you were profiling, himself. At times, he seems larger than life. Do you think that sort of character -- however much he may alienate people sometimes -- is necessary to lead a trip like this?

I think probably, in a certain sense, yes. Possuelo’s No. 2 was this guy, Paulo Welker, who was much more congenial -- more of a nice guy who wanted people to like him and who got along with everyone -- but an ineffectual leader. Nobody paid any attention to him whatsoever. The men rode rough-shod over him, didn’t pay attention to any of his orders, and didn’t have any respect for him. There is something to be said for a kind of iron-fisted leadership in which there is no questioning the authority of the guy in charge. There’s not much room for democracy in a journey like this, where you need to know where you’re going and how you’re going to get out. On the other hand, there were times when I sensed -- and I think a lot of the men on the trip did, too -- that there was a little bit of gratuitous cruelty.

Some readers might be surprised at how little anthropological interest Possuelo takes in the people he works so hard to protect. It’s something you seem to wonder about yourself, in the book. Did he ultimately convince you that his approach was right? Or do you think, in some ways, the trip represents a wasted opportunity: an arduous journey that may never be made again, with no attempt to learn new information about this isolated tribe?

I think he had a point. Indeed, considering how some anthropologists have traditionally worked in places like the Amazon, I think he had a really good point. It’s kind of like the social Heisenberg principle -- that you can’t study a group without changing them. There’s no way you can really come to know anything about a tribe without living among them, and there’s no way you can do that without contacting them. That whole process would begin to unravel the culture that the anthropologist would be studying.

It did strike me as a little bit odd that Possuelo did not personally seem to have more curiosity about some of these things. In the time since the expedition, when I sought to raise the issue of whether this tribe belonged to the Pánoan language family -- because it’s known that the Páno-speaking groups generally use blow guns, which is something that we found out as a result of this trip that was not known before -- Possuelo cut me off before I even could get the question out of my mouth. He said: “I don’t care. I don’t want to know.”

What’s also interesting is that he knows a lot about indigenous people, but he makes the point time and again (and I think I’ve mentioned it a couple of times in the book) that he is solidly opposed to the notion of “going native” -- participating in native ceremonies, or having himself painted, or any of those kinds of things. He maintains a respectful distance, and says, “Out of respect, I don’t enter into that kind of thing with the Indians I know.”

That hardly seems to get in the way of his rapport with them. You say he has an incredible ability to connect with the indigenous people -- that his humor, in particular, always makes an impact.

Exactly. And it was so interesting to see how much more at ease he felt among them than among his own.

Something else you touch on -- and I found this fascinating -- is the fact that relatively little has actually changed since the expeditions of earlier explorers. For instance, a lot of the modern navigational tools you could have used were worthless under the jungle canopy (without access to satellites) -- and it’s still common to make first contact with natives by leaving gifts for them, as early modern explorers did. How much do you think has changed over the past few centuries? Apart from the use of airplanes to map some of this area beforehand, this was a pretty old-fashioned operation, right?

That’s right. There’s not that much that we had with us that was any different from what 19th-century explorers had. (What perhaps sets the 19th century apart from earlier eras is the introduction of steam power, which allowed boats to travel deeper into the Amazon than ever before -- we were able to get pretty far toward our destination using traditional Amazonian boats.)

So we used fossil fuels to get us to the staging area where we began the on-foot part of the expedition, and there was a GPS; we also had a radio. It barely worked and only kind of fired up every couple of weeks, but it was critical in bringing in an airdrop when we stopped to build the canoes that would bring us back to deeper water.

But this type of expedition really does have the feel and the rigor of a bygone era of exploration. It was definitely a throwback to an earlier era -- and it’s very much like that in the Amazon. That’s how you explore in there, with these old techniques.

Once you were in the jungle, it seems like it was basically steel that set you apart from tribal communities; you used steel tools to set up camps at night and (briefly) tame small parts of the forest.

Correct. The value of steel is in the incredible amount of time and labor it saves on so many things. Which is why Possuelo said that the Indians understood the value of steel. It’s why they will risk a confrontation with white intruders to try to steal it -- because it is so valuable. In an hour’s time, our men could create an entire village in the forest with the steel that we had, and build canoes that were like battleships compared to the very rudimentary hollow palm trunk vessel that we saw, which belonged to the Arrow People. It’s steel, that’s right.

Have you ever read a work of fiction or seen a film that does this sort of environment justice? (I ask primarily because I read Ann Patchett’s “State of Wonder” earlier this year, and some of the scenarios from that book seemed recognizable in your account.)

Good question. Well, one book that’s really great -- and it’s not a novel, but it’s just a tremendous book, and it’s very funny, actually -- is a book written by Peter Fleming, the brother of Ian Fleming, author of the James Bond books. It’s called “Brazilian Adventure” and was written back in the 1930s. That’s really quite good.

A quick methodological question: When you’re on this sort of journey, how do you keep track of things? Did you bring a Dictaphone with you? You mention carrying around a set of notebooks -- were you scribbling constantly? Did you need to take time away from being with the group in order to get things down on paper? I couldn’t get a sense of how often you were making notes.

I did not have a Dictaphone. It’s all handwritten. I ended up with a staggering amount of notes from the trip; I think when I finally transcribed it all single-spaced, it was something like 500 pages.

I had notebooks with me, and whenever there was an opportunity to stop in the midst of the trek, I’d pull out my notebook and scribble something. I had to keep it in a Ziploc bag, and I sort of evolved this technique to keep it safe from sweat; I wrapped the notebook in the bag so I could write without getting the pages wet.

Every time we took a break for a second, I’d pull the notebook out. I might ask Possuelo a question and jot down his answer; in the evenings, I had this really great hammock that was very comfortable to lie in (it closed with a mosquito net), and that became an important refuge. Every night before I turned in, I would also write several pages and reconstruct from the last hours of the day or from other episodes from the day -- I’d make sure it all got in there. So it was a pretty rigorous kind of note-taking. And I rarely take the notes in Spanish or Portuguese; I translate immediately into English.

A lot has changed for Sydney Possuelo since this expedition took place; for one thing, he lost his job at FUNAI in 2006. Can you talk a little bit about the circumstances of his firing, and the work he’s been doing since?

My understanding of what happened is that he was out in the field visiting the Zoë Indians, and the head of FUNAI, the Indian affairs agency, was quoted as saying something to the effect of, “The Indians have a lot of land for so few people.” Contextually, I think the spirit of what he was trying to say was more like, “It’s going to be very difficult for us to withstand this rising tide of sentiment that the Indians have too much, and as resources dry up elsewhere, the pressure’s going to come on these lands.” Whatever -- it came out sounding like, “Yeah, they have too much land; we’re going to have to rethink our strategy.”

Possuelo was read the quote from the paper over the phone -- and he’s the kind of guy who just will launch into a tirade. It provoked him. He said, “I’ve heard this kind of talk before from loggers and land-grabbers and miners, but never from the head of FUNAI! I can’t believe it!” So he just spoke his mind, and he got fired. And he didn’t back down, either -- he didn’t say he was sorry or anything; he stuck to his guns, and so he got sacked.

It was a big blow, I think. There are not people in FUNAI of Possuelo’s stature [now] -- people who can really seriously defend the interests of the indigenous people.

After that, he formed an NGO; he’s tried to continue some of the same work he was doing, as an outsider. But my impression is that it’s much more difficult to continue doing this work from the outside. I’m not sure about this, but I suspect a lot of the funding that he was capable of securing before has kind of dried up. I know that some of the programs he started have continued, and they continue to get support from places like the Moore Foundation and the European Union -- but I don’t think they have the same sort of robust kind of budgets that they had under Possuelo.

Possuelo himself is currently in New Zealand; he’s been there with his wife, who’s on a fellowship. So he’s a little bit out of things now.

Does he have an obvious successor?

Well, there have been a number who’ve succeeded him in his old position. My understanding is that the person who is now in charge of the Isolated Indians unit inside of FUNAI is someone with good intentions but who does not have a great deal of experience. He’s more connected politically to the party and the president’s party.

Given these developments, do you think another expedition like this will ever be possible? Or at least, would it be possible in the near future?

Well, there will be other expeditions, but it’s unlikely that there’ll be any for some time to come, of the kind of ambition and magnitude of the one that I was on. There will be smaller trips, and there have been a few smaller trips, with fewer people, fewer resources, less time in the field, and probably less accumulated knowledge. But part of the mission of the Department of Isolated Indians is to continue to acquire as much knowledge as possible about these people, without entering into contact with them. So they will continue, but with fewer resources and with much less frequency.

It’s quite likely that the particular area where we were will never be explored again -- at least, not in the way we explored it. That requires a huge outlay of resources, and it’s a very sensitive area -- and very hard to reach. So it’s quite likely that there will never be a similar journey into the area that we traversed.

Shares