How much more are black people in this country supposed to take?

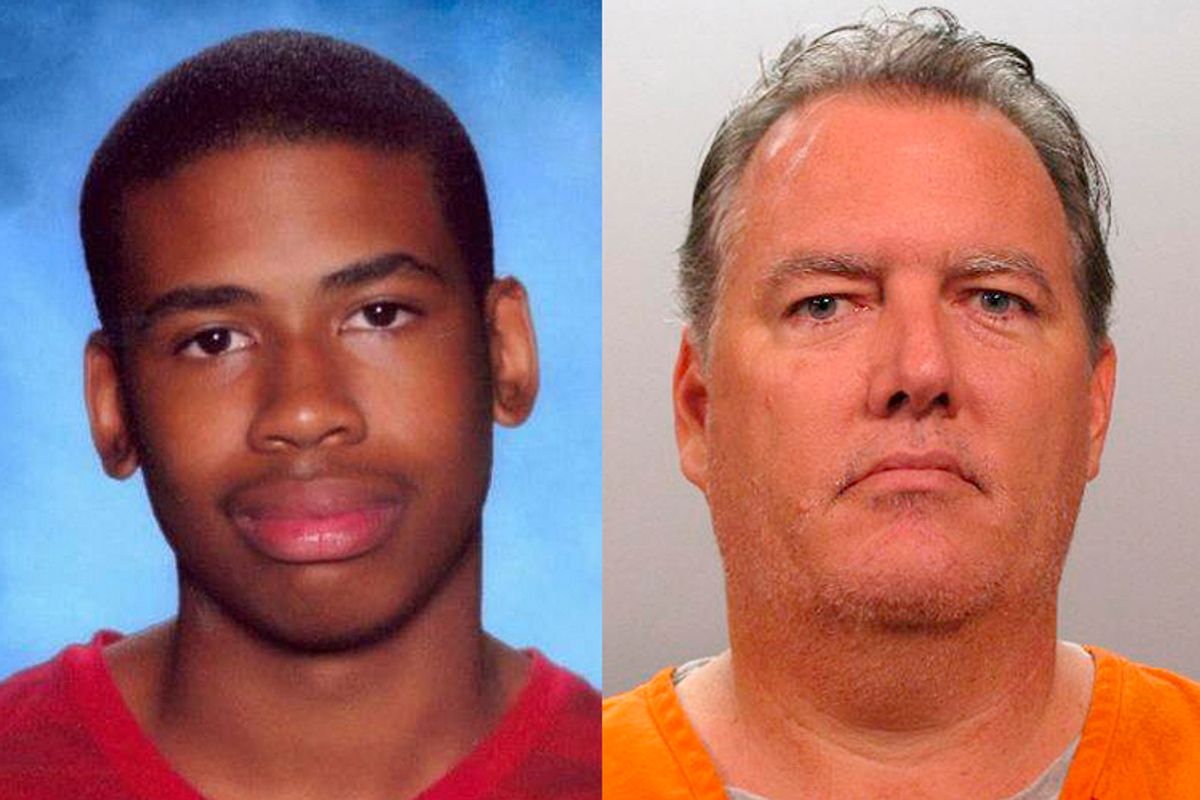

On Saturday, a Florida jury failed to convict Michael Dunn for the callous murder of Jordan Davis. Though he was convicted of three counts of attempted murder and also on a gun charge, a mistrial was declared for the first-degree murder charge. He will face substantial jail time – perhaps up to 75 years on the four charges for which he was found guilty.

Prosecutor Angela Corey has also publicly declared her intent to seek retrial on the murder conviction. However, she is the same prosecutor who oversaw the Zimmerman murder trial and failed to get a conviction. She is the same prosecutor who has overzealously prosecuted Marissa Alexander, for firing a warning shot into the wall to scare off her violent ex-husband. The Alexander case is the only case of the three for which she has gotten a conviction, and though Alexander has been granted a new trial, Corey intends yet again to send her to prison for 20 years for a crime that harmed no one.

Therefore, I don’t trust Corey. It is clear that Florida prosecutors are fairly unclear about how to defend black life against an onslaught of white murder.

Yes, I know that Jordan’s killer may spend the rest of his life in prison. But this is not about jail time. This case, like the case of Trayvon Martin, hinges on whether white fear legally outweighs and is therefore more legally defensible than black life. The day before Jordan Davis would have turned 19 years old, a court failed to affirm the value of his life, his right to exist in space enjoying music with his friends, his right not to be harassed by someone while doing something as mundane as sitting in a parking lot at a gas station.

Professor Angela Ards said of this decision, “The chilling social logic of this illogical legal verdict is that Dunn has been found guilty of missing the other black boys in the car, of failing to kill them all.”

I think it we can safely and fairly assume that it is open season on black teenagers, if the murders of Trayvon, Jordan and Renisha McBride are any indication.

I teach college students, and in the hopefulness and optimism of their youth, they are often quick to point out that racial politics are so “different in their generation.” But what I see is black students their age being murdered unceremoniously in locales throughout the country, by white or non-black men, who receive insufficient justice for their crimes.

Despite a belief in progress, this moment suggests that young black men’s audacity to exist is a capital offense punishable by murder.

And to be clear, this is not about the music Jordan Davis and his friends were listening to. The global dominance of hip-hop music and the often crass depictions of black life in which hip-hop artists traffic have made it an easy target and scapegoat for white racial anxiety. But white racial anxiety –and in particular the alleged legitimacy of it – is a foregone conclusion searching for facts. In this era, those “facts” seem to be readily available in endless media depictions of violent black males. In the post-Reconstruction era, those “facts” could be found in the swiftness of black progress during Reconstruction. During the tumultuous first half of the 20th century, those “facts” could be found in the audacity of black people’s desire to vote, share equal space on sidewalks, be paid fair wages, and eat at the same lunch counters.

Black being is the problem. Not black thuggery. Black boys officially exist in a state of social death, because the law continues to tell us that their lives, when taken by white men, are legally indefensible. They have been rendered by the law dead men walking. It’s no wonder then that in so many places they act like it. White thuggery, meanwhile, marches on, mowing down black folks at every turn, white sheets, sight unseen.

Many white folks believe that black criminality has produced white fear and that white fear in the presence of black masculinity is therefore always justified. But the opposite is true. White anxiety and fear and racism have produced the myth of pervasive black criminality. Intraracial black violence is a problem, but white racism has produced the concentrated structures of poverty and lack of access to education that give rise to violent behaviors.

Our national inability to tell the truth about this will only lead to more black victims.

In his famous essay “The Discovery of What It Means to Be an American,” James Baldwin wrote, “Every society is really governed by hidden laws, by unspoken but profound assumptions on the part of people, and ours is no exception.”

The truth we need to be telling is that the myth of black male criminality is foundational, not incidental, to America’s national identity. Even if there were no black male criminals, to riff on professor Hortense Spillers’ work, they would have to be invented. The presence of black criminals justifies white male rage, white women’s fear and subsequent white male violence.

The question is how should black people respond? Having seen a lot of violence in my childhood, I’m a deep believer in and practitioner of nonviolence. But in the face of unreasonable violence toward our children, why do black people owe the nation the safety of our reasonable, rational, nonviolent responses? Whether we take it to the streets or stay home and raise our sons and daughters, they are killed all the same.

Black people continue to believe that respectability politics will save us. Jordan Davis and Trayvon Martin both came from “good families,” with fathers who were present. Neither one of them lived to see their 19th birthday this month. Neither one of their killers has been convicted of their murders. How should black people respond? These killings and the inability of our justice system to do justice explode the bounds of reason.

My nephew turned 7 on Jordan Davis’ birthday. By all indications he and his big brother, aged 8, will be very tall men, like their father and grandfather who both hover somewhere around 6 feet, 6 inches. I know my little men to be great soccer players, lovers of Temple Run played incessantly on my smartphone, fierce competitors already, A students, hilarious dancers, sensitive and insightful souls, and a ball of giggles. But far too soon, their parents will have to talk to them about what their imposing body size will indicate to the general public. Where their white peers’ biggest fears will be handled in elementary school drills about tornadoes, hurricanes and thunderstorms, or maybe the perennial deranged young white male school shooter, my nephews will have to have safety drills of a different kind. It won’t just be “stop, drop and roll,” for them, but “Stop, hands up and make no sudden movements. Keep your anger and your fear in check. It just might kill you.”

This is unreasonable. In the face of all of it, black women lavish the men in our lives with the unreasonable love that our nation only knows how to give to white people. Playing surrogates for the nation is a job black women know quite well. In this instance, though, we are acutely aware of the insufficiency of our efforts. In the face of too much hate, our love is so clearly not enough.

Shares