Food stamps became part of American life 50 years ago this Sunday when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Food Stamp Act into law on Aug. 31, 1964. The program has been a whipping boy almost ever since, especially from conservatives who call the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, the contemporary name for food stamps) a costly and demoralizing example of government overreach.

But SNAP was not an idea first created by liberal do-gooders of the 1960s. Food stamps emerged three decades earlier with active participation of businessmen, the heroes of the exact group of people who want to see the program dissolved today.

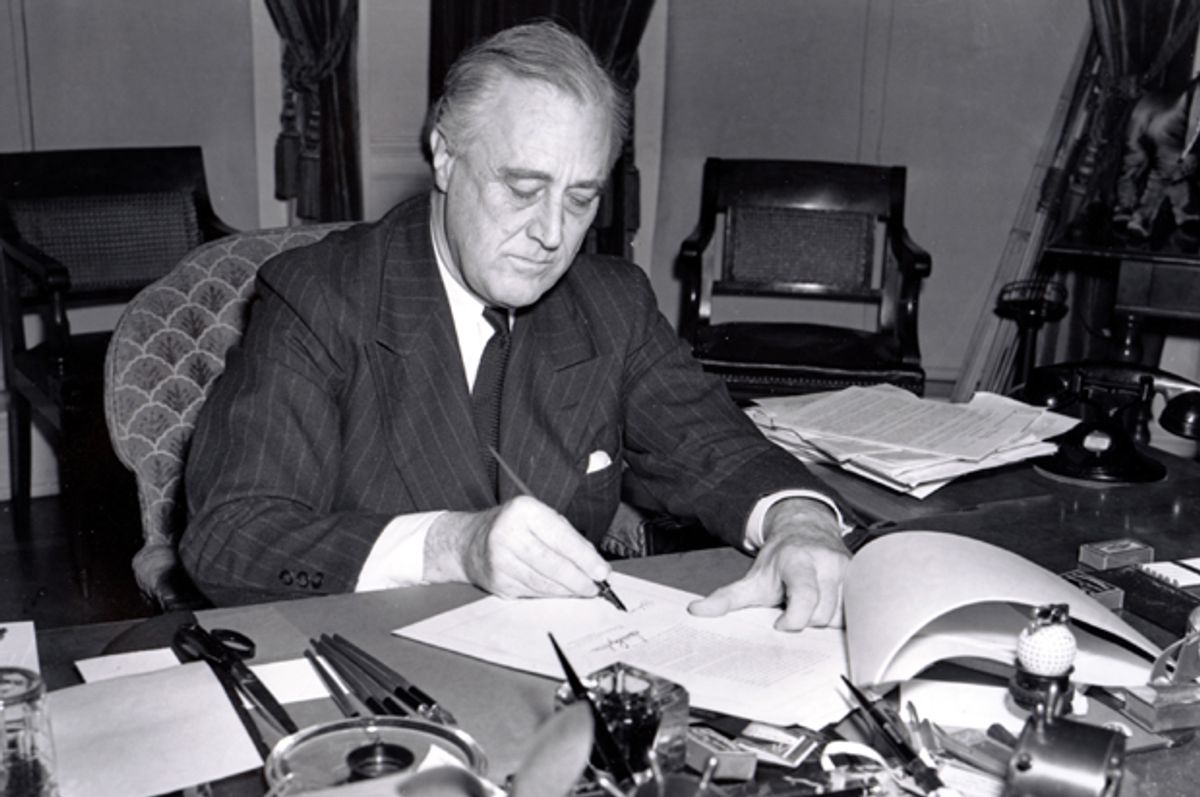

The early Great Depression was marked by a “paradox of poverty amidst plenty.” Massive crop surpluses led to low prices for farmers. At first, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration tried paying farmers to plow under surplus crops and kill livestock. In theory, decreasing the supply would raise farm prices incentivizing farmers to get their crops to market. But the plan was met with outrage from hungry citizens who said they could have put the destroyed “surplus” food to good use.

After this failed start, Roosevelt tried another plan. Government purchased excess crops at a set price and distributed them at little or no cost to poor Americans. But this system was also met with criticism, this time from the sellers of food goods. Wholesalers and retailers were upset that government distribution bypassed “the regular commercial system,” undercutting their profits.

The Roosevelt administration started the first pilot food stamp program in 1939 to integrate businesses in getting food to the hungry. However, there were concerns about the food stamp program’s success. A newsmagazine at the time reported, “there was no difficulty in selling the idea to grocers,” but some feared that the “real beneficiaries” wouldn’t cooperate. Unlike the image conjured up today of the poor clamoring for government aid, in the time of perhaps the greatest need in the past century, businesses were more excited about the federal assistance than the hungry individuals who were to benefit.

And it turns out businessmen had good reason for their glee; in the first months of the pilot program, grocery receipts were up 15 percent in the dozen “stamp towns.” Conservatives appreciated people “going through the regular channels of trade” and not relying on “government machinery” to bring food to people. The program proved to be so successful that it expanded to half of the counties in the nation by 1943. But the conditions that led to the program’s creation, high unemployment and large agricultural surpluses, disappeared in the WWII economy and the pilot program was shelved.

Twenty years later, the 1960 CBS documentary “Harvest of Shame” demonstrated hunger and poverty remained a reality for far too many Americans. Newly inaugurated President John F. Kennedy found it unconscionable that in the wealthiest nation on the planet, close to one-quarter lived in poverty without access to enough nutritious food to lead productive lives. He used his first executive order in office to reinstate the food stamp pilot program.

After JFK’s assassination, President Johnson reflected on the continued existence of hunger in America. However, the Texan was adamant that any government help would provide people with “a hand up, not a hand out.” Food stamps provided the perfect way to do this. JFK’s pilot program had proven that food stamps improved low-income families' diets “while strengthening markets for the farmer and immeasurably improving the volume of retail food sales.” And importantly, the poor purchased more food “using their own dollars.” Based on this assessment, LBJ made the Food Stamp Program a permanent part of the welfare state.

Much like grocers in the stamp towns of the late 1930s, grocery chains today continue to bring in increased sales from SNAP receipts during recessions. Remember last winter when stimulus funds expired and Wal-Mart disclosed lower than expected fourth quarter profits? While Wal-Mart refuses to disclose its total revenues from SNAP, it is estimated they took in 18 percent of total SNAP benefits in 2013, or close to $13 billion in sales. They publicly reported lower earnings per share as “the sales impact from the reduction in SNAP benefits that went into effect Nov. 1 is greater than we expected.”

SNAP recipients, then, are not the program’s only beneficiaries. Businesses profit handsomely from them, too. How ironic that in today’s concentrated grocery-retail market, the chains most ideologically opposed to welfare spending benefit the most from this welfare program. Even more ironic is the fact that the idea behind SNAP originated with grocery men in the 1930s who saw a way to route welfare spending through their businesses. When will today’s conservatives claim as their own these daring and entrepreneurial businessmen who, in part, made the Food Stamp Program possible?

Shares