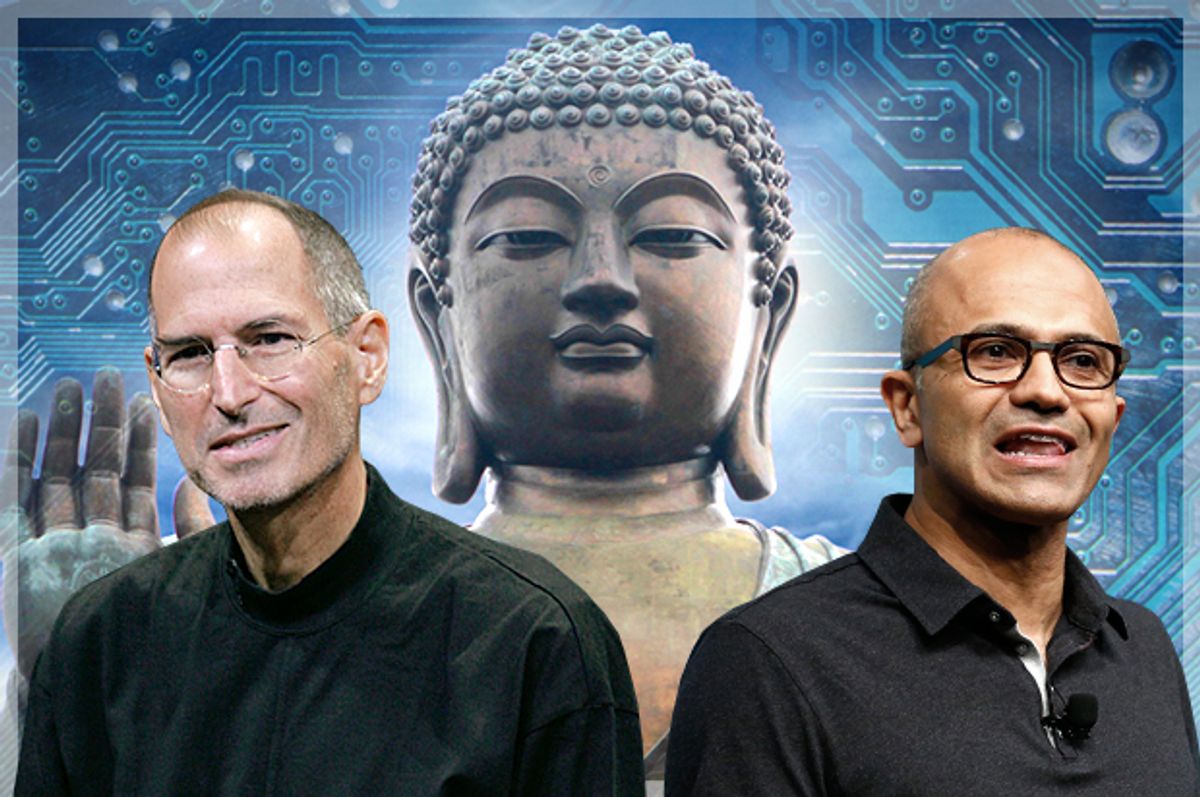

Recently, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella gave some shocking advice to a young businesswoman who was concerned that her male peers were passing her up for promotions: Don’t question the systemic sexism of corporate America, just trust in "good karma" to get you ahead. While his attitude made waves in the blogosphere, in fact it accurately represents a form of spirituality that is becoming popular in the West.

You know what I’m talking about. When I go to yoga, I’m often surrounded by wealthy white women who can afford expensive classes and Lululemon threads. When I scroll through my Facebook feed, I see exclamations of bourgeois spirituality (“Staying at the Waldorf tonight! #gratitude #blessed #100happydays #livelife"). Moreover, my actor friends seem to use karma and positivity as tools to help them achieve commercial success.

We might call this a belief in spiritual meritocracy. The implicit idea here is that our professional and financial growth depends on our spiritual merit, not on the presence or absence of social structures and biases. We are told that if we are grateful enough, if we put enough happy energy into the universe, then we will be rewarded with material wealth and earthly pleasures. (Think "The Secret.") We are told that we actually can have it all: a rich spiritual life, leading to a rich material life.

Of course, this is just the new-agey equivalent of the same old meritocracy myth that’s been floating around America since at least the 19th century; that in the land of the free, anyone can become rich if they just work hard enough, if they use the right brand of elbow grease.

Unless you are a rich Republican, decades of widening economic inequality should tell you how faulty this story is. While it is true that most successful people work hard, the meritocracy myth works more to justify an existing social hierarchy than to inspire us to make positive social changes.

So, for the same reason we look suspiciously on Horatio Alger-esque theories of social mobility, we ought to also be skeptical of their spiritual version, which says that underserved groups can get ahead not by standing up to power, but by focusing on love and positivity.

It’s times like these when I am reminded of Slavoj Zizek’s summary dismissal of “Western Buddhism.” Zizek cautions that while meditation may seem to come from an edgy counterculture, in fact Americans practice it in a way that is often consistent with consumerist capitalism:

“... although 'Western Buddhism' presents itself as the remedy against the stressful tension of capitalist dynamics, allowing us to uncouple and retain inner peace and Gelassenheit, it actually functions as its perfect ideological supplement ... One is almost tempted to resuscitate the old infamous Marxist cliché of religion as the 'opium of the people,' as the imaginary supplement to terrestrial misery. The 'Western Buddhist' meditative stance is arguably the most efficient way for us to fully participate in capitalist dynamics while retaining the appearance of mental sanity ... ”

In other words, rather than helping yogis become more socially conscious spiritual warriors, Buddhist meditation can get hijacked by the status quo. It only brings us a shallow peace that makes us less likely to question what counts as normal.

For the last seven years I have dedicated myself to a Buddhist meditation practice, and I believe that there is some truth to Zizek’s harsh critique. As I have become more skilled, I have enjoyed moments of sublime bliss. And the more mindfulness I developed, the better I got at daily activities. I got a little better at surfing, playing poker, driving; the truth is, meditation helps me achieve whatever goals I set for myself, whether that’s being kinder to my friends and family, or earning more money.

One problem with a capitalist-inflected Buddhism is that it can lead us to a kind of spiritual cul de sac. I found that my practice was in an uneasy tension with my leftist politics. I found myself attracted to a glamorous Santa Barbara lifestyle that left me feeling unfulfilled and disappointed. I found that it became easy to deal with disturbing images in the news by dismissing the suffering of others as the karmic products of their own poor decisions. (They’re just not being positive enough!)

Yes, I found myself tempted by tales of spiritual meritocracy.

Overall, I am happy that my Facebook friends and yoga moms are finding spiritual enrichment. But I believe that focusing only on the joyful aspects of spirituality can get us into trouble, if we aren’t careful. Every religion can get appropriated by the West’s consumerist ideology, and Buddhism is no exception. When we cultivate gratitude for our material wealth and ignore compassion for those less fortunate, comments like those of Nadella are a natural consequence.

In traditional forms of Buddhism, there are bits and pieces of teachings on karma that capitalism loves to pick up on. Our society emphasizes an interpretation of Eastern spirituality that does not threaten its own internal logic. It’s true, for example, that the Buddha taught that money was a blessing, and that one effect of an ethical way of life would be material prosperity. But it is hard for me to believe the Buddha would say that wealth inequality is solely the result of karmic patterns, and that we should ignore its hidden histories of slavery, colonialism and patriarchy.

The good news is that there may be a spiritual antidote for what Tibetan teacher Trungpa Rinpoche called “spiritual materialism.” And I’m not talking about intermittent bouts of Catholic guilt. I’m suggesting that if we work to complement our gratitude with mercy and compassion for those who are less fortunate, we can move away from the surface-level spirituality that is really just materialism in disguise. And this may be what the world needs more than ever.

There are plenty of opportunities for us to be compassionate. For example, as scientists’ long-term projections of the effects of climate change become more and more dire, somehow American denial of anthropogenic global warming is on the rise. This kind of denial is only possible if it is not met with compassion for those who are already facing the extreme weather of hurricanes like Sandy and Katrina, like the hard-hit women who are struggling to survive after flash floods destroy their communities. Cultivating compassion for those we usually ignore — whether that’s women in the global south who are facing the ugly end of natural disasters, inmates of American prisons, or businesswomen who make 20 percent less than men who do in the same job — is therefore both a spiritual and political imperative.

The point is not that we give up on Western spirituality, as Zizek seems to suggest. The teachings of Eastern religions are becoming more mainstream in America, but this is an opportunity as well as a cautionary tale. As we develop a more conscious lifestyle, let’s ask ourselves if we are deepening our spirituality, or just falling for the myth of spiritual meritocracy. May all beings be free from pain and suffering.

Shares