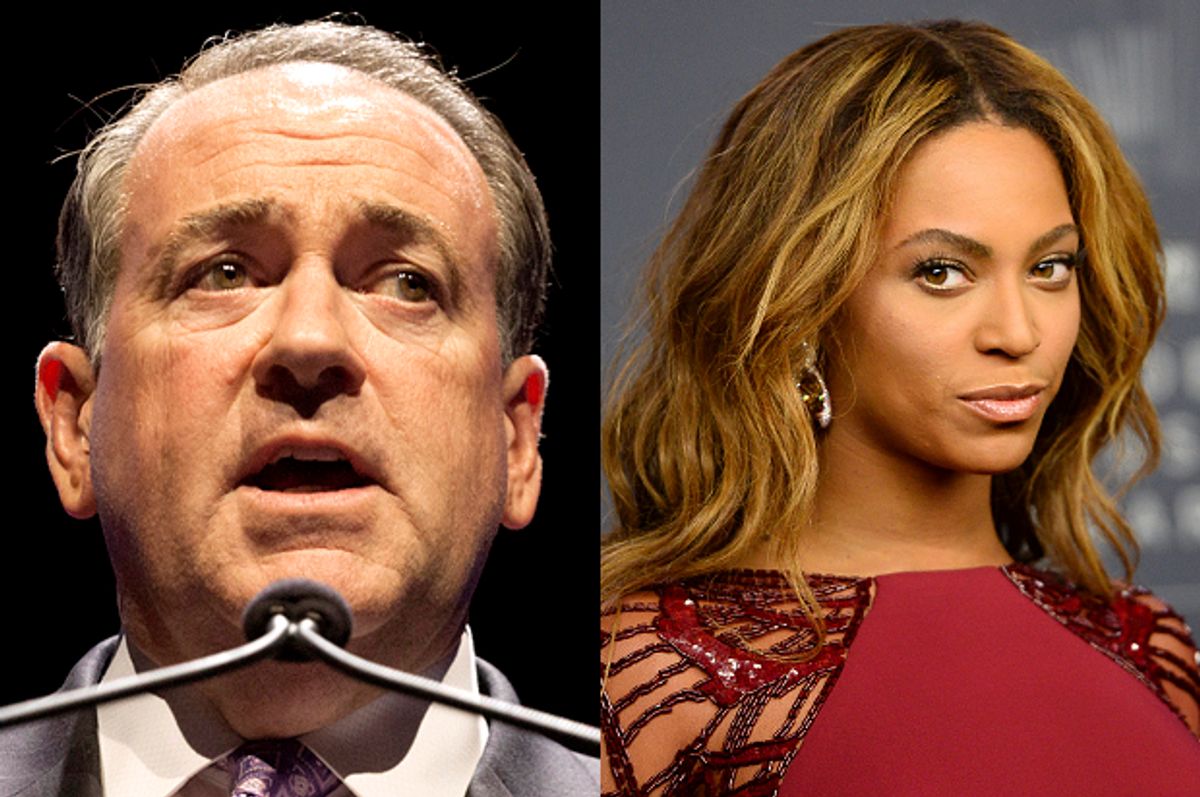

In an interview promoting his recent book about American Christian political identity, Mike Huckabee commented that he doesn’t understand how Barack and Michelle Obama let their daughters listen to Beyoncé. He told ABC that he doesn’t think Beyoncé is wholesome, referring to Biblical ideas about holiness, saying, “what you put into your brain is also important, as well as what you put into your body.” Huckabee, a white man, seems to take particular focus on Beyoncé, stating in his book that it seems her husband, Jay Z, has crossed the line from husband to pimp in “sexually exploiting her body.”

I want you to hold that moment in your head for a minute – a white man calling a black man a “pimp” and criticizing a black female singer for being too sexual in her music. Let’s talk about history.

In the Oscar-nominated movie "Selma," there’s a particularly poignant moment when clergy and people of faith from across the country respond to the call to come march in Selma, Alabama. Ministers and clergy travel to the small town that is the center of a voting rights conflict, and get in line behind Martin Luther King, Jr., Andrew Young and John Lewis as they march to the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Route 80. These clergymen and -women did this knowing the stance they were taking was a risky one – one Unitarian Univeralist minister named James Reeb would later be killed by a white mob who considered him a traitor to the white race.

Just over a century before these moments portrayed in the movie, Huckabee’s own Southern Baptist Convention was born. This denomination, which has grown to nearly 16 million members, was founded in a historical break from Northern Baptists in 1845 – over a question of slaveholding. In the South of Dr. King and Fr. James Reeb, the Southern Baptist Convention was a main portion of the white opposition to the black civil rights movement. Leaders have acknowledged, time and again, that their denomination stood on the wrong side of history.

But even as Ferguson overtakes the media and the historic marches from Selma to Montgomery are chronicled in a film many are calling the best of the year, the SBC remains relatively silent on issues of race. The denomination is still, by and large, made of a powerful political bloc of white voters who self-identify as evangelical. The SBC is not only the largest Protestant denomination, but it is also the largest group of self-identified evangelicals in the United States – a group that encompasses about one third of the American Christian population.

“Evangelical,” as an identity, is separate from the historical nature of the Southern Baptist Convention, though their theologies and histories are tied together and, in many ways, are nearly inextricable from each other. But evangelical, as a political and social identity, has a much shorter history than the Southern Baptists. The sanitized story that you’ll hear from most evangelicals is that, following the 1973 decision of Roe v. Wade, evangelicals were moved away from their previous apolitical identity toward protecting the unborn. Much of the evangelical identity, even today, is centered on pro-life issues and pushing for political protection of fetuses. And this is an identity Huckabee embraces as a former pastor and current evangelical thought leader.

But Evangelicalism actually dates back to well before Roe v. Wade – indeed, about a decade before, right around the time Martin Luther King, Jr., was becoming a national figure. The historical white religious fear of the black man is a well-documented phenomenon. After all, Emmett Till was murdered for the supposed crime of whistling at a white woman. Social hygienists in the early 1920s created sexual health education not out of a public health concern, but because upper-class white women were beginning to mirror the supposed sexual habits of lower-class people of color. The pearl-clutching fear over miscegenation was still in the minds of evangelicals as they began to stand up as a political identity in the early 1960s.

The landmark decision of Loving v. Virginia – the interracial marriage court case of 1967 – spurred yet more white fear over the loss of control over white women in particular. This fear coincided with the rise of second-wave feminism – which would eventually lead to Roe v. Wade. All this tumult threw the evangelicals into a political fervor – the way of life they had established for themselves in the two short decades since the end of World War II was coming to an end. Life in the U.S. was, in a word, unstable. This change didn’t sit well with evangelical leaders.

The black church and the white church in America have always existed as separate, simultaneous entities. During the days of slavery, white slaveholders recognized the power of the black church as a place to plot revolt, and therefore began forcing their slaves to attend their white churches with them. Martin Luther King, Jr., was a reverend and famously talked just as much about God’s will as he did the politics of the day. Evangelicals, then, found a way to respond to the civil rights crisis by injecting their own take on scripture and race into the discussion.

Through this narrative, the purity movement as we know it today developed – full of True Love Waiting and abstinence-only education and purity balls. The threat of black men to white women’s purity is still a ghoulish nightmare in the minds of white evangelicals of the 1980s, when Falwell’s Moral Majority rose to power and when Huckabee was most active as a pastor in Arkansas. The cultural wars, imbued with the memory of the civil rights battle just a few years before, were the training ground for Huckabee’s pastoral and theological thinking.

And it is in this context that Huckabee can call a multimillionaire black musician a prostitute and a sexual object without his base of white evangelicals batting an eye. It is this history – a history of Evangelicalism founded in racial tensions and racist fear over the sexuality of black people – that colors Huckabee’s comments to make them seem entirely reasonable to an audience of white evangelicals primed to gobble them up. Huckabee’s comments, indeed, are carefully calculated dogwhistles to his base, imbued with the racist history of the political evangelical identity.

Shares