Withholding evidence. Government business carried out in secret. Potential criminal investigations.

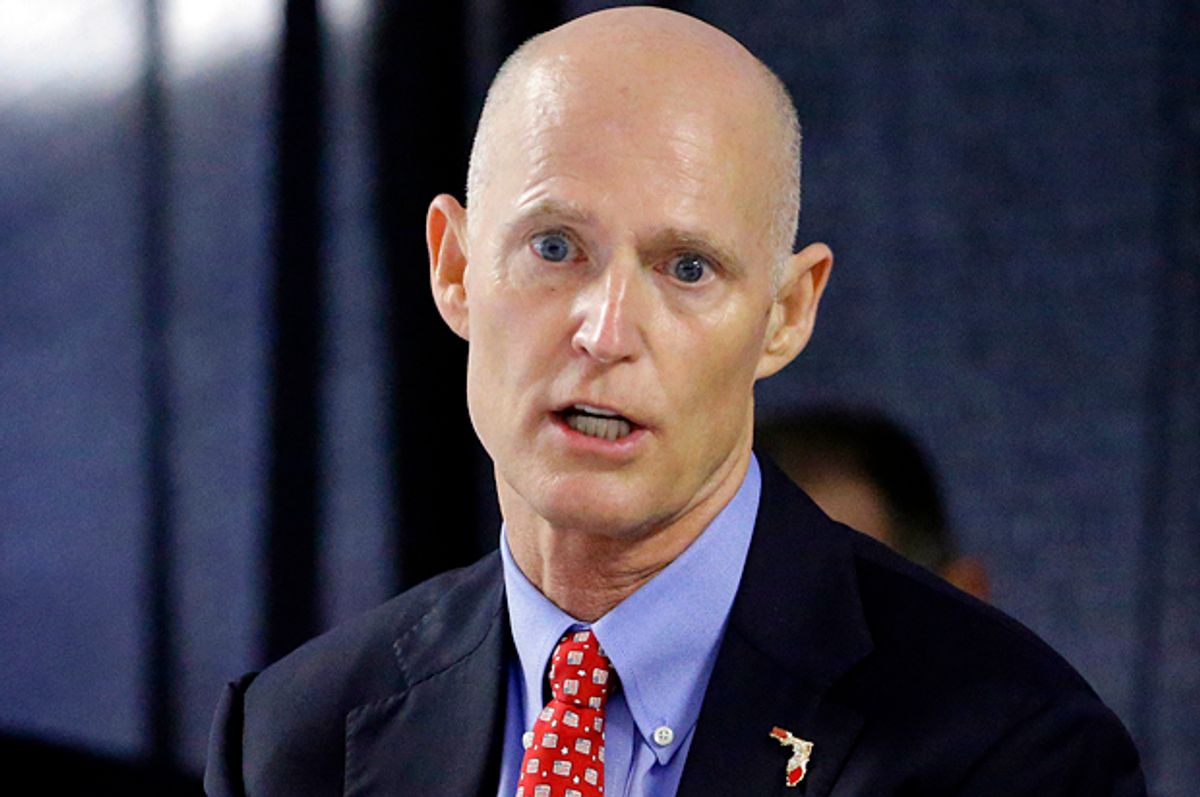

I’m not talking about the allegations surrounding former Oregon Gov. John Kitzhaber, who resigned on Friday. In Florida, a similar cloud has formed around Gov. Rick Scott, who faces three separate lawsuits alleging violations of a number of state laws.

In any normal political environment, the charges would lead to calls for resignation or impeachment proceedings. But Scott appears insulated by the very expectation of his corruption. In idealistic Oregon, Democrats controlled every level of government, and forced out a member of their own party. In Florida, the governor is supposed to be a scoundrel. But even if Scott survives, Republicans seeking the White House in 2016 might have a problem associating themselves with the leader of the biggest swing state, especially if more of his Nixonian tactics are revealed.

“This governor has completely evaded all public records on everything,” said Matt Weidner, a St. Petersburg attorney who filed one of the three lawsuits against Scott. His complaint involves the sudden firing of Gerald Bailey, former executive director of the Florida Department of Law Enforcement (FDLE) and a respected public official.

Scott initially argued that Bailey simply resigned. But Bailey has since spoken publicly, accusing the governor of lying about his ouster (an email from Scott’s general counsel demanded that Bailey “retire or resign”) and attempting to politicize the independent FDLE. According to Bailey, Scott’s office pressured him to hire political cronies and forced FLDE officers to chauffeur Scott campaign staffers.

This came to a head when Adam Hollingsworth, then Scott’s chief of staff, asked Bailey to name Orange County clerk of courts Colleen Reilly in a criminal investigation. “Somebody drafted an order from a judge saying ‘Go release these criminals from prison’ and submitted that to the court, and the Department of Corrections let these guys out,” Weidner told Salon, describing a prison break based on forged documents. “Rather than hold the Department of Corrections accountable, which is in the executive branch, the governor directed Bailey to target this clerk. And Bailey said I’m not going to target her, she hasn’t done anything wrong. And the governor says you’re gone.”

Where this turned potentially illegal is in possible violations of Florida’s Government in the Sunshine Law, actually a robust series of transparency statutes around public meetings and records. Under that law, conversations between the governor and other statewide elected officials in his cabinet about staffing decisions must be open to the public and recorded with minutes. But through conduits, Scott and the cabinet secretly discussed firing Bailey, and hiring his replacement Rick Swearingen, sidestepping the Sunshine law. Cabinet members say they were told Bailey voluntarily resigned; Swearingen didn’t know about the firing either.

Swearingen was hired in a largely ceremonial public cabinet meeting on Jan. 13. In video of the cabinet meeting, which features state Attorney General Pam Bondi parading around a dog for adoption and a series of photo opportunities, Gov. Scott abruptly launches into legal boilerplate about appointing Swearingen. His nomination approval takes just a few minutes, without any debate. “Why don’t we take a picture,” Scott says at the end.

“The suit is enforcing the public’s right to know,” said Weidner, who also requested that the state attorney in Tallahassee open a criminal investigation into the Bailey firing. “Reporters are making records requests and saying where is the back and forth? It doesn’t exist. The government is being operated in total secrecy.”

Every major newspaper in the state has joined the Weidner lawsuit, though the cabinet has generally shrunk from the controversy. Scott apologized for Bailey’s firing in a cabinet meeting last week, maintaining that he did nothing wrong.

But with questions about Bailey swirling, the continuity between this lawsuit and others against Scott adds to the pressure. Two years ago, Scott sued Tallahassee attorney Steven Andrews over a land dispute involving a proposed expansion of the governor’s mansion. Andrews used the case to ask for all public records around the issue, and in turn, discovered that the governor and top staffers operate a series of secret email accounts.

Scott at first denied the existence of the emails, but then released documents showing Scott’s personal Gmail account being used to discuss vetoes and the state budget. Staffers solicited fundraising through the private accounts, using personal cellphones and having checks sent to their homes rather than the office. The final email releases came after his hotly contested reelection campaign; Scott’s lawyers successfully delayed court orders to turn over the emails until after Election Day.

This is critical because public officials in Florida must release any emails related to state business upon request (former Gov. Jeb Bush released them preemptively last week). Failure to turn over those emails when asked for violates the law. Andrews got a judge to allow him to amend his complaint to say that the governor knowingly violated public records requests, an impeachable offense in Florida. The administration continues to fight to get the suit tossed.

A third lawsuit comes from George Sheldon, who lost as the Democratic candidate for attorney general in 2014. He accuses Scott of violating state ethics laws by inaccurately reporting his personal wealth on financial disclosures. The lawsuit alleges that Scott’s disclosures to Florida vary widely with his disclosures to the Securities and Exchange Commission. While the SEC documents reflect a net worth of at least $340 million, Scott’s Florida financial disclosure from last June lists it at $132.7 million. And Scott’s net worth “bounces wildly without explanation,” Sheldon claims in the suit, with selective disclosure from year to year.

Sheldon believes that Scott has maneuvered money through a network of trust accounts to hide it from public scrutiny. Scott has refused to deliver information on the trusts, calling the lawsuit a “frivolous partisan attack” and claiming that the discrepancies with the SEC documents have to do with Scott’s wife Ann’s money. Scott’s lawyers want to move the case out of court and into the state ethics commission, currently chaired by a Republican appointed by the governor.

Scott came to office with a reputation for chicanery. As CEO of Columbia/HCA, he presided over the largest Medicare fraud in history. His job approval rating is just 42 percent, months after his reelection. But there’s a sense that Scott gets graded on a curve, that corruption that would be shocking elsewhere is seen in Florida as normal.

“People who should know better have become conditioned to believe that that’s the way it is,” said attorney Matt Weidner. “You’re sitting there going this is wrong and somebody needs to do something, but will anybody stand up?”

Because of this bias, the spate of allegations may just sit there. But national Republicans need to win Florida in the 2016 election, and they may not want to get wrapped into the seedy political culture in a GOP-dominated state. They may pressure the party to abandon Scott; you can already see Agriculture Commissioner Adam Putnam, a former member of GOP congressional leadership, distancing himself and questioning Scott’s truthfulness.

As the three cases wind through the courts, advocates believe Scott could find himself trapped, as ugly details of how he runs the nation’s third-largest state spill out. “Will this be the ultimate of holding people accountable,” asked Matt Weidner. “In a proper world it would.”

Shares