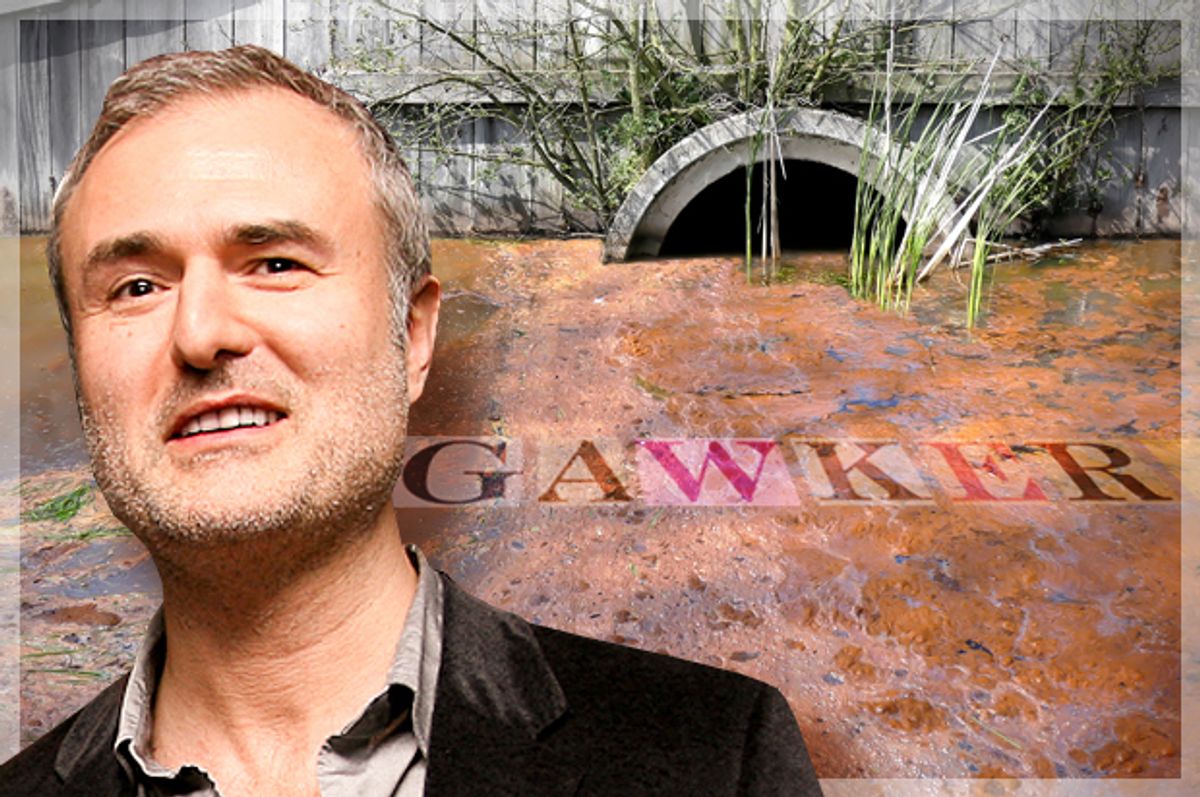

There are so many ways to be sanctimonious about the recent and abrupt implosion of Gawker, the confrontational news and gossip site that has long positioned itself as the rebel frontiersman of the Internet. (That gendered noun is deliberate.) I cannot possibly avoid them all, so I may as well haul out numerous platitudes at once. Those who live by the sword, or in this case the scourge, are liable to die by it. Every revolution, no matter how small and self-invented, creates its own version of the Reign of Terror, and then its own Thermidorian Reaction, when the radical leaders are themselves sent to the guillotine. Are those overly grandiose ways to describe the meltdown of a deliberately scurrilous tabloid-style website? Well, of course, but such was Gawker’s sense of mission. We could put it Jeff Foxworthy-style: If you grow a beard, live under a bridge and dine on billy-goats, you might be a troll.

Over the last 10 days, Gawker’s backed-up internal contradictions have come bubbling into the open like the contents of an overheated outhouse. On July 16, the site ran a story naming a married male executive at a New York publishing company who had allegedly pursued a paid sexual liaison with a male porn star -- based entirely on information supplied by the porn star, whose identity was protected. That was thoroughly reprehensible, but I’m not at all convinced it represents Gawker’s editorial low point. That might have been the anonymous 2010 article by someone who claimed to have had a drunken (but chaste) one-night stand with Republican senatorial candidate Christine O’Donnell, a masterwork of misogynistic trollery that united the entire Internet in defense of a Tea Party nutcase.

Let’s pause here for a moment of Gawker-style transparency, shall we? Salon’s editorial staff recently signed on with the Writers Guild of America, the same union that Gawker’s staff voted to join a few weeks earlier. It would be ludicrous to pretend that those events were unconnected: The WGA has been working to organize online journalists at numerous publications, and the staff at Gawker blazed the trail. But if anyone in their union has had any contact with anyone in ours, I don’t know about it.

This time around, the tide of near-unanimous outrage provoked by what looked like the gratuitous outing of someone at a competing company penetrated the thick hide Nick Denton, Gawker’s mercurial founder and publisher, who has never previously behaved as if he cared about criticism. He took down the post a day later, apparently after extensive internal debate and a 4-2 vote of Gawker’s managing partners, and issued a public apology in the form of a thumb-sucking meditation on his newfound maturity: “The media environment has changed, our readers have changed, and I have changed.” Denton stopped just short of saying he had been reborn in Christ, but I imagine that’s coming soon.

In the next act of this comedy, Gawker’s two top editors, Max Read and Tommy Craggs, who were under the understandable impression that they had done exactly what Denton was paying them to do – i.e., publish true or at least plausible sleaze about anyone and everyone deemed to be outside the Gawker circle of coolness -- then resigned in high dudgeon. Rather than saying what I just said (“Dude, you told us to wade fearlessly into the ooze, and we did, so STFU!”), Craggs and Read set themselves on fire as martyrs to the cause of journalistic ethics and editorial independence, of all things. It was a dazzling display of misguided entitlement and self-righteous vanity, the hipster journalist equivalent of Douglas MacArthur’s Farewell Address. (Max and Tommy: Go ahead and Wikipedia him. No shame!)

Anyone who attacks Gawker or Denton – a London-bred, Oxford-educated onetime Financial Times reporter who reinvented himself in New York, reverse-Gatsby style, as a maverick outsider -- runs the obvious risk of being perceived as a defender of the hoary conventions and institutions Gawker longs to tear down. (Or at least that Gawker says it wants to tear down, which may not be the same thing. Sometimes the yearning to destroy is just yearning, full stop.) Even a second-string Gawker writer should have no difficulty depicting me as an aging bohemian who still pines for invitations to Susan Sontag’s cocktail parties and drug-addled evenings at CBGB, simultaneously wearing dad-pants and clutching my pearls while shouting at the kids to get off my lawn.

Well, bring it – but here’s the funny part. On both a personal and an intellectual level, I relate strongly to the challenge that Gawker threw down before the cozy, self-congratulatory culture of mainstream journalism and its masturbatory relationship with fame, power and money. To the extent that Denton and his legions of staffers over the past 13 years have understood the conventional ethics of journalism as a smokescreen meant to conceal a mendacious gravy train of managed information, I’m right there with them.

Read Stephen Kinzer’s book “The Brothers,” or my former boss David Talbot’s forthcoming “The Devil’s Chessboard,” and you learn how CIA head Allen Dulles seduced many of the so-called great men of postwar American journalism, including Arthur Ochs Sulzberger of the New York Times, Ben Bradlee of the Washington Post and almost every major political columnist, into becoming shills for hysterical anti-Communism and belligerent Cold War foreign policy. Judith Miller, the Times reporter and Bush administration stooge who did so much to drag us into the Iraq quagmire, is not nearly as much of an outlier as she seems. Miller was just an extreme example of the snuggly relationship with power, and the subtle but pervasive channeling of public discourse through well-worn grooves of accepted dogma, that has characterized mainstream journalism for decades.

In its better moments, Gawker has presented a bracing antidote to the corrupted professionalism of Judy Miller and her ilk. Its writers have certainly never relied on the tone of studied, neutral obfuscation that NYU professor and journalism blogger Jay Rosen calls “the View from Nowhere.” I have often found reading Gawker to be a deeply unpleasant experience, and its embrace of an ethics-of-no-ethics has ensnared the site in its own mythology, as we can see in the disastrous outing story and the hilariously inflated missionary zeal displayed by its clown posse of departed editors. But the Schadenfreude expressed in many journalistic circles over Gawker’s current plight is not edifying. I certainly hope Miller and Denton do not represent the only possible roads to the future of journalism, but only one of those people repeatedly published lies that killed thousands of people and will bankrupt the country into our grandchildren’s generation.

Without quite realizing it, Gawker (and many other online sites) inherited significant strands of its oppositional DNA of 1980s and ‘90s alt-weekly journalism, that vanished realm where I began my career and made my own hilarious mistakes. In large part, the story of Gawker belongs to a larger narrative about the economic and technological disruption that severed Internet, blog-era journalism from its cultural predecessors, creating what has often been described as an chaotic Wild West environment with no apparent standards or rules. That sense of freedom is both intoxicating and dangerous, and one of its pitfalls is the enshrinement of a new orthodoxy: “No standards or rules” becomes the new rule, rather than a problem to be worked out.

As the editor of SF Weekly in a year so deep in the past that most of Gawker’s current staff was being perverted by the Teletubbies, I once had to go on Spanish-language TV and explain why our cover illustration of the Virgin of Guadalupe on a burrito was not racist or offensive. “Soy católico,” I said to the nervous young reporter, which by any reasonable standard was a bald-faced lie. Some months later I attended an earnest meeting with local leaders of GLAAD, who were deeply concerned about the epithet that sex columnist Dan Savage wanted readers to use when they wrote him letters. (It’s a word I pretty much cannot use in Salon in 2015.)

I would have rejected any notion that some one-size-fits-all ethical code covered both situations, and I still do. But by interacting with people in the real world I came to understand that I was bound by practical and political considerations, and despite my overweening arrogance I learned something from those experiences. I still believe the burrito Virgin was totally defensible, by the way, but the fact that I had no Latinos or fluent Spanish speakers on staff was not. On the other hand, strategic retreat on Savage’s “Hey, F****t” was well advised, despite the fact that several lesbian and gay colleagues, including the publisher who was my immediate superior, had no problem with it.

Nick Denton just had his own interaction with political and practical reality, on a much grander scale. Only in the fantasyland apparently inhabited by Read and Craggs is anyone other than the publisher the final arbiter of what runs and what doesn’t, or the ultimate authority who must face the consequences. I suppose late is better than never: Denton’s newborn sense of editorial responsibility and professed desire for a kinder, gentler Gawker only arrived after he had built a $300 million media empire in a dozen years, on a site that refused to recognize any distinction between exposing the abuses of the powerful and invading people’s privacy for no discernible reason. (His change of heart also might have something to do with potentially crippling litigation: Gawker already faces an enormous lawsuit from Hulk Hogan after broadcasting the wrestler’s extramarital sex tape, and might face another from the outed publishing executive.)

Consider Max Read’s jaw-dropping tweet last Thursday night, before Denton had decided to take the executive-outing story down. Read assured the world that Gawker would “always report on married c-suite executives of major media companies f***ing around on their wives.” Really? Toward what end, young man -- and who the hell appointed you the guardian of media morality? Oh, that’s right – you appointed yourself, with zero awareness of how much you sound like a censorious old biddy from a Frank Capra film. (Note the assumption that married executives are by definition male and heterosexual, and that the marriage could not possibly be polyamorous or non-monogamous.) Subtract the profanity, a sure sign of rebel edge (if this were 1963), and Read’s sexual politics fall just slightly to the right of Rick Santorum and the Catholic League.

I don’t have much to add to my colleague Mary Elizabeth Williams’ account of becoming a special target of Gawker’s bile at the same moment when she went public with her life-threatening cancer diagnosis. I’m obviously not a neutral observer; Mary Beth is an old friend who also goes back to the alt-weekly era in San Francisco. But here’s the important point: We’re not talking about whether a Gawker reporter or anyone else has the right to dislike her writing and say so. We’re talking about the editorial judgment that abdicates any standard of editorial judgment, and at a deeper level about the flawed understanding of power that has dogged Gawker from the get-go.

Gawker’s journalistic Jacobinism is a lot like American exceptionalism, one of numerous ways in which the site’s posture of apolitical ruthlessness is fundamentally reactionary. Everything Gawker does flows from the perception that everyone else in the media has immense unearned power, but that there is one anointed publication (owned by a large and profitable company and read by millions of people) that guards the doorway of virtue with a flaming sword, like the archangel Michael of the Internet. What public benefit or cultural purpose could possibly be served by heaping unctuous slime on a woman who believed she was likely to die young and leave her daughters motherless?

None, of course – except for the burnishing of Gawker’s collective sense of manifest destiny and glorious self-importance. Undisciplined cruelty came to be understood as Gawker’s principal tool and central method, as the way to prove its moral purity and divine purpose. Modulating or adjusting that signal in any way would be a craven capitulation to bogus norms the Gawkerites believed they had left behind. If you’re not willing to slut-shame Christine O’Donnell, heap pointless snark on Mary Beth Williams and publish every B-minus celebrity sex tape you come across, than you somehow lose the ability or authority to go after Bill Cosby or Rob Ford or other targets who actually deserve the full Gawker treatment.

All sorts of things went wrong at Gawker, but as I have suggested the central problem was not the site’s original impulse to view the complacency of 21st-century consumer culture through a lens of radical skepticism or even cynicism. Those have always been the healthiest things about Gawker. The bad stuff arose from the highly variable ways that impulse played out in practice, and particularly the overwhelming tendency to focus on the sins of prominent (or supposedly prominent) individuals, while largely ignoring boring and unsexy structural issues like corporate criminality or the misuse of state power or the vast Ponzi scheme of the American economy.

That focus on individuals rather than institutions is a distinctive ailment of our neo-pagan age, in which organized religion has largely been replaced by celebrity worship and/or celebrity demonization. Gawker’s biggest stories have almost always been granular revelations about the crazy stuff someone did, which deliberately avoided larger questions of power and politics and feel, in retrospect, devoid of social meaning. What did we actually learn about Internet misogyny from the 2010 “doxxing” (i.e., public exposure) of an especially noxious Reddit moderator named Michael Brutsch? Did Gawker’s publication of private emails between Rep. Chris Lee, a married New York Republican, and a woman he met on Craigslist tell us anything new about conservative hypocrisy? I’m not convinced that the Lee story is ultimately much better than last week’s retracted porn-star fiasco. Are someone’s extramarital shenanigans (or, in both of these cases, proposed or hypothetical shenanigans) inherently newsworthy just he’s an elected official? Only if he's a Republican? Or a family-values scold?

I’m not sure, but those are clearly questions of editorial judgment, a human factor that is highly subjective, prone to error and utterly irreplaceable. After a dozen years dispensing the Gawker Kool-Aid of “radical transparency” and insisting that anything that was more or less true and likely to attract eyeballs was therefore worth publishing, Denton has finally realized that his powerful media venture requires actual grownups at the tiller. Back in his undergrad days at Oxford, I bet he read the thrilling passages in Nietzsche’s “Daybreak” where the mad German philologist works out his argument that Christian morality is only a repressive social fiction that must be discarded. It’s taken Nick this long to get to the next part, when Nietzsche says that many of the things described as “immoral” are in fact things we probably shouldn’t do, but not because of some empty set of rules handed down from on high. We have to work out real reasons for our actions, which is the most difficult part of freedom.

Shares