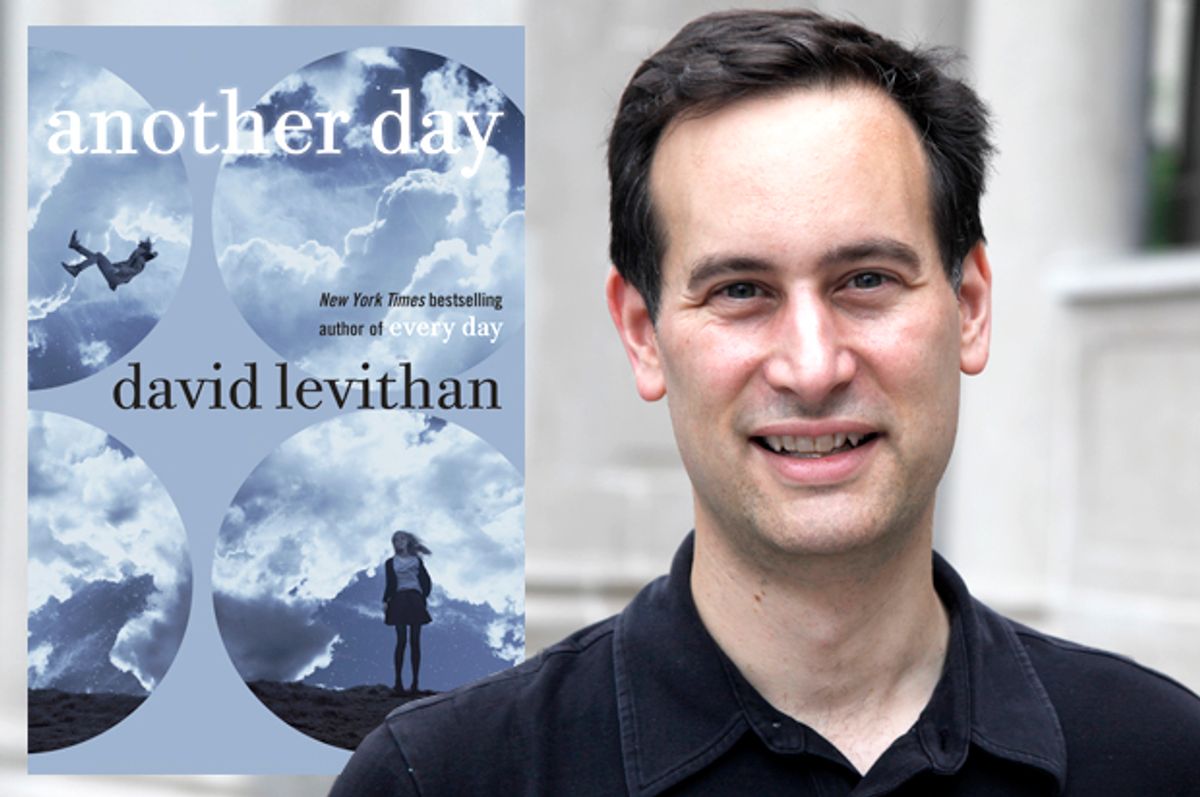

What if, from day to day, you woke up in the body of a different person, so that in fact you were borrowing someone else’s body instead of ever inhabiting a body of your own? This is the premise that David Levithan explores in his young adult novel, "Every Day," and again in "Another Day," just published, where he tells the story from the point of view of the girl that this bodiless “A.” falls in love with. Levithan isn’t just an accomplished writer — he’s also a publisher and editorial director at Scholastic Books, and has worked on many culturally influential novels, including "The Hunger Games" and "The Baby-sitters Club" series.

I recently had the chance to chat with him about his latest book and diversity in the publishing world.

You call “Another Day” a companion to “Every Day” instead of a sequel. How did you come up with the idea for the first book, and what made you want to write a book from Rhiannon's perspective?

The two go hand in hand. With the first book, I wrote a book to answer two questions and did not know the answer when I started writing, and by the end I sort of knew what my answers were. The first was what would your life be like if you weren’t defined by your body? If physical characteristics did not define you who would you be and who would you be able to be? That really fascinated me. Secondary to that was if you were in love with somebody who was not defined by their physical characteristics, you are in fact in love with somebody who changes every day. How would that work? Would love conquer all or would it in fact be difficult? I felt that I did in fact cover both questions in the first book, but definitely felt that because it was told through A.’s point of view that I covered the first one much more thoroughly and more through A.’s view of things than the second.

I did not know when I wrote the first book that I would write a second book from Rhiannon’s point of view, but interestingly it started with brainstorming. We were trying to brainstorm bonus material or extras for the first book and I thought it would be sort of neat to rewrite the first chapter through Rhiannon’s point of view, to flip into that very, very intense day, but through the lens of somebody who did not actually know what was truly going on. Within two or three pages of writing in Rhiannon’s voice and seeing through her eyes, I thought “Oh, this isn’t bonus material. This is actually another book, because this will actually let me answer that second question so much more.” That was really how the first book evolved and then how the second book evolved within the first book.

Was it difficult to write this book with much of the same plot, but told through the perspective of Rhiannon? How did you tackle that? Did you have to have the first book out and closely examine it as you were writing this?

Yeah. It’s the same story. I keep joking that had I known I would be using the dialogue twice I might have done the dialogue differently the first time. It was really interesting and I really liked it in this way because it became purely about perspective for me. I, as a writer, never, ever, even when I say I’m going to, never outline or plot out things ahead of time. I write the story to find out what the story is. This book was the antithesis of that, where I knew not only what the story was, but pretty much every major beat within the story. I had to both make it interesting for myself to write and obviously interesting for the reader to read. That was really where the perspective came in. What was interesting to me, and hopefully will be interesting to readers, is that the smaller things and the smaller plot points are the things that A. can’t know about because A. is not there in the first book. Those took on a really interesting importance and gave the story a lot more depth in different ways than the first book had.

In Rhiannon’s point of view you say, “Part of me wants to ask A about this, to ask, Are you a he or a she? But I know the answer is that A is both and neither, and it’s not A’s fault that our language can’t deal with that.” Do you think we are making progress as a society in talking about both gender and sexuality in fair and open ways?

I think there’s some progress. I think we need much more progress, but I think especially in the past year with the trans identity and the issues of trans equality and making sure that both life and the language encompasses a gender-fluid identity or a gender-transitional identity. I think that is something that was not necessarily on a lot of people’s radars before, but is certainly on their radars now. I think people are making attempts, or many people are making attempts, to try to make that legitimate. When writing "Every Day" that was certainly very much on my mind. It was very interesting because I philosophically knew it, but it was talking about it that made me really understand the linguistic part of it. A. really does have no set gender, and in realizing our language did not really have any way to grapple with that — that was so fascinating.

As an editor I’m publishing a book called "George" that comes out the same day as "Another Day" comes out (on August 25th.) It’s about a trans elementary school student who basically comes into her own. The author identifies as the pronoun “they.” The character everybody sees as a boy, but she identifies as a “she.” It’s been interesting to see the reactions to that too, which really go hand in hand with what A. has to deal with.

When you say reactions you mean from media reviews, people reading it early?

Yeah. Most people make a well-intentioned attempt to call people by the pronoun that they choose to be called by and to refer to a character by not a default gender, but by the gender or non-gender that they are. I think people try that and get caught up in it. And in the same way I will sometimes slip and call A. a “he” or “she” and will be like, “Oh no. Why did I do that?” It’s so ingrained in us. At the same time there are certainly other people who don’t get it, who are very dismissive of the attempt and don’t understand the terms behind it. They’re like, “A. is a ‘he.’ Why do you bother? Why would any one person identify as ‘they?’ That makes no grammatical sense.” The notion that we have to identify people by gender doesn’t necessarily make grammatical sense either.

How did schools, libraries, and booksellers react to "Every Day?"

It’s really been almost universally positive. It’s been interesting because most, especially librarians, are very open-minded and are really there to introduce people to new ideas and not to keep people away from new ideas. I think certainly as far as acceptance of the storyline and where the discussion of the storyline is concerned, I think it is the paranormal element, it is the science fiction twist to it — science fiction isn’t the right term — but it’s the waking up every day in a different body that sort of allows them to talk about these issues. Whereas if it were a book about two boys kissing, where it is about a very set identify, very bounded in the real world, that is actually what people get upset about more because it is too close to comfort for them. It’s an interesting psychology. I think there is a grand tradition of science fiction and fantasy to address real world problems under the guise of science fiction and fantasy. That’s where change is made.

I know you’re very involved with the #WeNeedDiverseBooks campaign. As both a writer and an editor you have addressed this a little already, but how far have we come and where do we need to go? What do we need to do as a society and in the book world in general to get there?

Again, it’s empowering authors to write the stories that are true to them and true to either their experience or the experience of somebody whose voice is not being heard. I think there is a wonderful wave of empowerment that’s happening, that people are being emboldened to tell these stories in whatever way they want to. Whether it’s a straightforward memoir, whether it’s fiction, whether it’s science fiction — I think there is an openness to that that is progressive and I think it changes as society changes … I think it is about finding a diversity of voices. With #WeNeedDiverseBooks people have done a wonderful job of really harnessing that and making it their mission. Not just to point out what isn’t there, but to actually create the things that fulfill the gaps of what isn’t there by giving grants to young writers, to give recognition to authors who are on the same mission. That’s the way to go.

In the new book Rhiannon says, “When my friends see this body they assume they know a lot about the person inside of it. And when people I don’t know see it, they also make assumptions. No one really questions these assumptions. They are this layer of how we live our lives.” That’s so true. We form opinions around the superficialness of our bodies rather than what’s underneath. I love that you’re addressing this through the eyes of a teen because teens are at an age where they deal with this judgmental behavior even more than most adults do. Are we as a society still stuck in high school in some ways, not willing to see past first appearances?

Absolutely. Especially as our attention spans get shorter and shorter and our world gets quicker and quicker. We are so much more inclined to make the easy snap judgment or the shorthand call rather than the long, thoughtful response. I think that through judging people immediately by their appearance, is the easiest and fastest way we do that. It’s an incredibly hard thing to rewire even if you have the best of intentions to not be judgmental in that way. It’s the way we are taught to see the world. I think that so many of the conversations about race and about gender are questions of appearance and the reaction to appearance with a lot of cultural history behind it. The good thing is I think people are having these conversations more and more. I think the voices are being understood more and more, but they certainly aren’t going away.

I love the idea of inhabiting a different body every day and how every day is different. Every day offers surprises. A. doesn’t get to see how the life of a person he or she is inhabiting changes from day to day. I was curious what you would do if you were leading A.’s life. Would you try to make a difference in the lives of others? I’m thinking of a particular scene in the book where Rhiannon encourages A. to get help for a suicidal girl whose body he/she is stuck in.

I think it’s such a hard judgment call. What’s interesting to me about A. is that A. is such a moral person and is trying not to cross the line except in that particular case when there is harm involved, where there is harm to yourself or harm to others. I like to think that if I were in the same situation that that is how I would live it. I’m sure I would learn that through a lot of trial and error. I’m often asked, “Whose body would you want to be in if you could be in anybody’s body?” And I’m constantly saying, “No.” In fact writing this book and really spending years thinking about it has made me hopefully understand how miserable of an experience that would be. The idea that you could wreck somebody else’s life so easily just by something you don’t even know you’re doing, that is terrifying to me.

How does your day job as being publisher and editorial director at Scholastic impact your writing?

I play with other people’s words during the week and play with my own during the weekends. There are things I learn about words from the authors I work with. I take note of them. I do luckily feel that they are very different, that when I’m editing I don’t feel even remotely like I’m writing. When I’m writing — I’m sure my editor wishes I would feel like I’m editing while writing, but I really don’t. It’s two variations of the same theme. I have an interesting vantage point to look at literature as a whole and as I said before, my first book, "Boy Meets Boy," clearly I was writing the book I was wanting to find as an editor. As an author I decided to write it. With some very notable exceptions, the LGBTQ YA spectrum was a very dark and miserable spectrum. Most of the stories being told about gay teens were ones about suicide, depression, and violence and outsider status and being an outcast. I was so sick of that because that did not reflect reality, or all reality. So I fueled my fire and wrote "Boy Meets Boy." Everything I have written after that started with that. In those ways, knowing what’s there and what’s needed, I think my day job informs that, but they definitely are separate to me.

You’ve talked about writing books you also want to read, ones you see missing from the publishing landscape. You’ve edited many well-loved books, including some of the titles in “The Baby-sitters Club” series and “The Hunger Games.” How have YA books changed over the course of your career, and why did it take adults so long to embrace the genre? There was snobbery towards it for so long, but in the past decade many adults started reading young adult books.

It’s been really interesting to watch the evolution of the perception of YA. I think that YA itself has always been very bold and has always been a place where authors can really write with such emotional truth. I think that teenagers connected with that, but now, as you said, adults are connecting with it just as much. There’s something really exciting about that, but as far as why I think it’s just the Harry Potter generation was just so energized by books and that spread through YA. Then when they were no longer teenagers there wasn’t this feeling that you had to disown the past in order to go forward. They continued to read YA as well as adult books. The accurate perception is whereas many adults used to think of YA as being books for teens, they realize now that YA is books that includes teens. There is no talking down. There is no oversimplification. It really is something that speaks to their lives and most of the emotions we had as teenagers are the ones that are still very very prevalent as adults.

What do you look for as an editor? What excites you when you’re looking to find a book you want to publish?

I think there is the emotional truth to it. There’s the creativity to it. Again, when "George" came on my desk, the book that’s publishing the same day as "Another Day," within three pages I was in tears. It’s such an extraordinary evocation of this girl’s life as being seen as a boy and her emergence as who she is supposed to be. It’s told with such beautiful simplicity and power. It was just that raw connection of like “Wow, this is a story that is not being told, but is being told here so beautifully, I have to publish this.” The reactions aren’t always so visceral, and certainly I think emotional truth can be found just as much in fantasy and science fiction or mystery or other genres. It doesn’t have to be realistic fiction that brings about the truth. I think that people love Harry Potter because it feels real to them. That quality is certainly what I’m looking for.

Towards the beginning of “Another Day,” Rhiannon recalls her day spent with A. when A. was inhabiting Justin, before she knows that her boyfriend that day was really A. She says, “I remind myself that yesterday is all about a choice, but not every day allows us to make our own choices.” Later on in the book you bring up how A. and Rhiannon both hate "The Giving Tree" because the tree gives everything to the point that it sacrifices itself. How can we have more opportunities to make our own choices? Isn’t that what stories are all about in some ways, to learn what our choices are?

It is true. Again, both books are so much about the internal and the external. While the external has constraints and there are always going to be constraints, whether you are the teenager who has to go to school everyday or the adult who has to go to work everyday, there will always be things that you have to do. But the internal is where you are free. That’s the part where, yes, you can find creativity, you can find inspiration, you can find love, you can find all these other things to live for and live through that are choices and are not as constrained as the external or physical are. The difference between the two books is that A. has been living with that since A. was born so A. has an understanding of that [and] has managed, in some ways, to transcend the external. Whereas Rhiannon, the book is interesting to me because she will never be able to transcend in the way that A. can. Instead, it’s about balance. It’s honing the internal and being as in touch with the internal as you can, letting your thoughts go where they want to go even if your body can’t necessarily go where you want it to go.

Shares