Last week, Matt de la Peña became the first Latino author to win the Newbery Award, the most prestigious prize in American children’s literature. “Last Stop on Market Street” had already racked up an impressive number of awards, so the fact that it took the Newbery was not exactly a total surprise. But given that the picture book was not only written and illustrated by creators of color but focused on a bus ride taken by young, underprivileged black child and his grandmother, diversity advocates let out a great cheer that this book had received such unprecedented recognition.

“Last Stop on Market Street” also was honored with a Caldecott for Christian Robinson’s illustrations, but the top award went to “Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear,” written by Lindsay Mattick and illustrated by Sophie Blackall. Why does Blackall’s name sound familiar? Late last year, the picture book she'd illlustrated, “A Fine Dessert,” was considered a top contender for the Caldecott. It not only ended up on numerous “best of 2015” lists, but generated a furious controversy over her illustrations of smiling slaves.

After listening to critiques of the book's depiction of slavery, the author, Emily Jenkins, apologized via the librarian’s book blog, “Reading While White,” where she stated that she donated her fee to the children's book advocacy organization, We Need Diverse Books. (Full disclosure: I’m a member of the We Need Diverse Books team, though I am not in any way speaking here as its representative, and was not involved with any aspect of Jenkins' donation.)

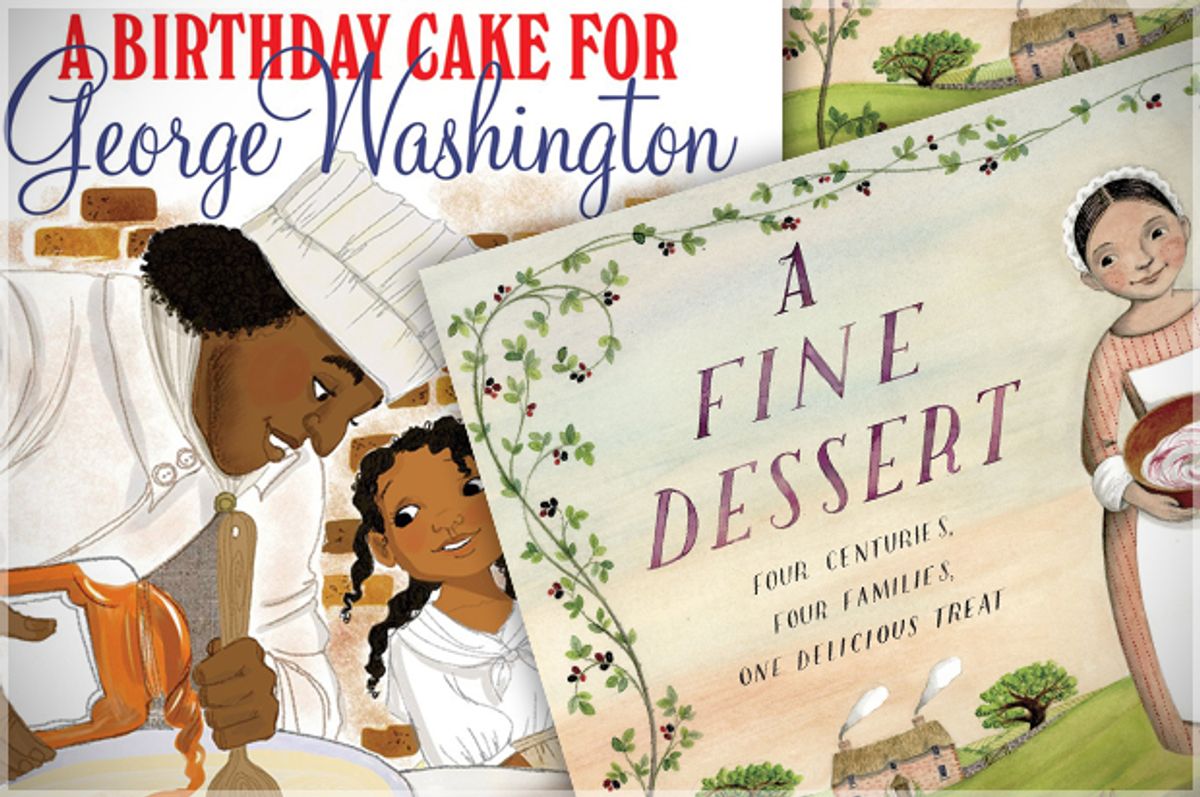

Blackall won the 2016 Caldecott for "Winnie" because she is a gifted illustrator, and it is not my intention to scapegoat her for the amnesiac tendencies of American culture. For the larger issue is the fact that her depictions of slavery in “A Fine Dessert” went unchallenged by so many gatekeepers, confirming that the bones of the book publishing industry are still stubbornly white, and will doubtless remain so for some time. For even as love was being heaped on creators of color at the 2016 Newbery and Caldecott Awards, a children’s book called “A Birthday Cake for George Washington” quietly made its debut. Like “A Fine Dessert,” it is a “historical” illustrated book featuring smiling slaves working hard in a well-equipped American kitchen.

Having seen an advance copy of “A Birthday Cake for George Washington,” the children and teen book editor at Kirkus Reviews, Vicky Smith, was moved to write a preemptive apologia which nonetheless failed to notice that the illustrator, Vanessa Brantley-Newton, called the slaves “servants,” as if they just happened to be at the low end of a social hierarchy, and were “happy” to have a great job working for such a powerful man. And yet, Smith pointed out, the book’s author, Ramin Ganeshram, inadvertently gave “the lie to this statement” in an author’s note telling readers that the main historical character featured in the book, a slave named Hercules, left behind his young daughter Delia when he escaped. Smith concludes: “It's easy to understand why Ganeshram opted to leave those details out of her primary narrative: they're a serious downer for readers, and they don't have anything to do with the cake. But the story that remains nevertheless shares much of what 'A Fine Dessert'’s critics found so objectionable: it’s an incomplete, even dishonest treatment of slavery.”

Yesterday, Scholastic announced it was stopping the distribution of "A Birthday Cake for George Washington" and would accept all returns. "While we have great respect for the integrity and scholarship of the author, illustrator, and editor, we believe that, without more historical background on the evils of slavery than this book for younger children can provide, the book may give a false impression of the reality of the lives of slaves and therefore should be withdrawn," the publisher's statement said.

How, then, should children’s book authors and illustrators approach the subject of slavery in early American kitchens? Is it better to simply avoid the topic altogether as being inherently unsuitable for picture books? African-American culinary historian Michael W. Twitty blogs at Afroculinaria and is the author of the forthcoming book "The Cooking Gene." He's an expert in the history of race, slavery and American food. In an email to me, Twitty explained: “Children must learn about slavery in the United States and in the Western world in general, because, to quote the last Republican campaign, 'We built this.'" He adds: “I think the illustrator of 'A Fine Dessert' meant well in depicting the role of enslaved people as part of the plantation household, but it's the smile that confuses us. We smiled to hide our feelings. ‘We wear the mask that grins and lies.’”

The trouble is that readers who have never considered slavery from the slave’s point of view will tend to interpret those smiles as benign, irrespective of whether the illustrator intended them as smiles of mother-daughter love, or smiles of pleasure at a job well done. But “our people weren’t eating that dessert,” Twitty asserts. “Being enslaved wasn’t a job or a joy, it was being a non-citizen and a non-human. I think for those who have worn the period clothing and done period cooking on plantations, it’s easy to see how such a rosy depiction can later translate at best to ignorance and at worst indignant surprise at the sensitivity Black Americans express at the depiction of their past as a mercy.”

The asymmetrical economic framework of food labor is the great unspoken in both of these picture books. It’s because they purport to relay “history” while remaining disingenuous about their own motives that so many hackles have been raised. The wrongs of slavery are not reducible to race. They extend to exploitative economic systems that understand crops as commodities and bodies as labor, enslaving humans as a means to extract greater profits. As Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Fogel and economist Stanley Engermann argued in their controversial study "Time on the Cross," slavery is an economic institution, perpetuated because it was both efficient and profitable. The moral cost to society was nothing compared to the wealth it could generate, not only enriching slaveholders but the larger community.

It’s easy to wag a judgmental finger while feeling all smug and superior regarding how far we as a society have progressed from those days, but books like “A Fine Dessert” and “A Birthday Cake for George Washington” continue to extract profits from the legacy of slavery by perpetuating institutional racism, which is still hiding behind the thin yet exceedingly effective veneer of moneyed respectability, using pretty pictures and lovely words to hide the essential ugliness of the practice. In other words, it’s not the subject matter that’s the problem, but the way it’s being uncritically used to sustain social inequality and damaging cultural expectations.

Stylistically invoking 19th-century folk art, Blackall replicates a colonialist aesthetic rendered in pastels. Visually, it’s charming, but it not only fails to interrogate the violent foodways that produced the spectacle of abundance on the table, but actively works to suppress the imagination from raising uncomfortable questions as being impolite and offensive. Bad manners. Rude. Biting the hand that feeds you. It doesn’t trace Blackberry fool (a “fine dessert” referenced by the title) as prepared by 18th century leather tanners, by 19th century prostitutes, and 20th century truckers living in rusted-out double-wides, to echo the chronological arc of the book. It doesn’t even feign the sentimentalized pauper’s kitchen featured in kid lit from Charles Dickens' “A Christmas Carol” to Roald Dahl’s “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.” No, the interpretative lens focuses on the social privileges of the leisured class, and that’s why the horrors of slavery are downplayed in both efforts. To expose the suffering of slaves unmasks the narrative work of reinforcing bourgeois conventions as a moral good.

Now, this may seem a heavy critique to bring to bear on books aimed at 4-8-year-olds. But slavery is a heavy subject, and to diminish the complaints of black readers because it’s just a children’s book is the very epitome of white privilege. The fact that the creators of “A Birthday Cake for George Washington” are people of color doesn’t change the critique, except to illustrate that the expectation that their ethnicity would somehow make the authors, in the words of Smith, “race traitors,” (!) is to misunderstand “diversity” as being about identity politics. The project aims, rather, toward decolonizing the imagination. From there, the institution will follow.

Which brings me back to the awards. Overall, the annual meeting of the American Library Association was a great one for diverse books in general, with the Asian Pacific American Library Association (APALA) giving top prize to Jenny Han’s "P.S. I Still Love You” in the Young Adult category, and Rafael López winning the Pura Belpré Illustrator Award for “The Drum Dream Girl,” written by Margarita Engle. But the Newbery is the big one, and Matt de la Peña’s win is both well deserved and instructive. He showed that it’s possible to tell a story that doesn’t shy away from harsh social realities, yet retains the innocence of childhood tempered by a grandmother’s wisdom. And that, to my mind, takes the cake.

Shares