If there’s one thing everyone agrees about in the current Oscar controversy (and there probably isn’t), it’s that Hollywood’s marquee event is fighting a long, losing battle to seem relevant and meaningful. Exactly how many nominations is Eddie Redmayne going to get for movies that nobody actually wants to watch? There is some inherent risk in a white dude making this argument, but the #OscarsSoWhite problem is a symptom of a whole range of deeper problems in the American movie industry, rather than the disorder itself. While the Academy’s emergency plan to expand and diversify its membership is certainly not a bad idea, it has the distinct flavor of telling the brass band on the deck of the Titanic to play a different tune.

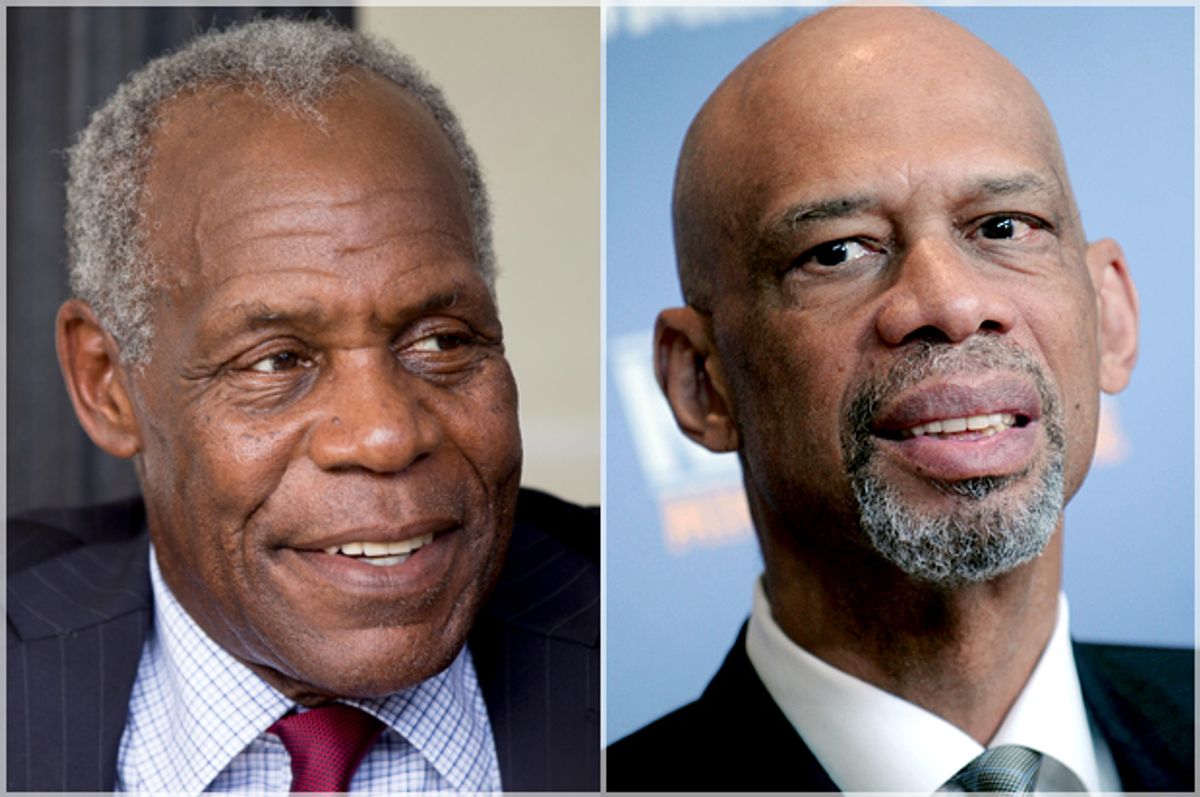

Looking past the proximate issue of whether a few prominent African-American celebrities like Will Smith and Spike Lee will choose not to attend the Oscar spectacle next month—and of course what host Chris Rock will say about it in his opening monologue—the fact remains that nobody has any real idea what to do about this. In the last few days we’ve heard two of the most interesting and astute progressive voices in African-American culture express this clearly, while arriving at virtually opposite conclusions. Danny Glover thinks that the Oscars, and all other awards shows, no longer reflect lived reality or the films people actually watch, and should be abolished. After framing the issue of institutional racism in eloquent terms, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar suggests that the Oscars are a crucial part of the entertainment economy and that for better or worse we are stuck with them.

In a moving interview with Variety at Sundance, Glover suggested that the cultural isolation of Hollywood epitomized by the Oscars had become anachronistic. “I don’t see diversity in the film world at all anymore,” he said. “We need to talk about the process, the democratization of making movies, not 15 men deciding, ‘You’re going to see this movie this year, and then this movie.’” Awards shows have always reflect the subjective judgment of a self-selected in-group, Glover went on, and that group has become more out of touch with ordinary people’s lives and desires than ever. “Maybe we should do away with them.”

That might sound strange coming from a guy who starred with Mel Gibson in a long-running action franchise, but Glover is well known in the film world for his activism and his radical politics. I’m sure he’s never been interested in the Oscars, and has devoted much of his later career to funding and supporting all kinds of small adventurous films far away from that realm, including Abderrahmane Sissako’s confrontational docudrama “Bamako” and Lars von Trier’s “Manderlay” (in both of which he also acted). I don’t imagine Glover really thinks the Oscars will be abolished anytime soon: As historians will tell you, the authorities of ancient Athens handed out awards to dramatists and actors every year, and people complained about it.

But whether the Oscars might abolish themselves, in a certain sense, by sliding so far down the slope of cultural irrelevance that they don’t much matter anymore, is a different question. That’s the issue Abdul-Jabbar raises in a guest column for the Hollywood Reporter this week. The legendary Lakers and Bucks center’s celebrity career is intriguingly different from Glover’s: As one of the first prominent Black Muslims in the NBA, Abdul-Jabbar was often assumed to have radical views. That was never really true, and since retiring from basketball he has become something of a Renaissance man, a thoughtful but never overheated commentator on race, religion, culture and sports.

Abdul-Jabbar readily admits that in any given year there might be no performances by black actors that merited Oscar nominations. It could even happen two years running. He doesn’t take that any further, but one could: Hey, no one of Polish descent was nominated this year, and that’s a substantial demographic group too! But there is an important difference. No one would find it remotely credible that Academy voters and studio executives operate on ingrained, unconscious prejudice when it comes to Polish actors, or might have a tendency to overlook the roles they play and the films they make.

Some considerable proportion of the Academy’s membership feels grievously injured by all the uproar, and I’m sure those people will seize on Abdul-Jabbar’s opening gambit: Of course we’re not racist! Look at all the awards we gave “12 Years a Slave”! We voted for all the performances we liked best, and this was how it fell out this time around. Yeah, all right, and last time too. Idris Elba is a talented fellow and all, but that character in “Beasts of No Nation” scared the crap out of me! He’ll get his shot when he plays some noble warrior who suffers for a good cause.

OK, I don’t think anybody has actually said that stuff about Elba in public, or in print, but it’s a reasonable assessment of how that particular non-nomination went down. This is where Abdul-Jabbar comes in. After admitting the hypothetical possibility that no black actors deserved nominations, he goes on to explain why almost no black person will see it that way, quoting the famous words of Ralph Ellison’s narrator in “Invisible Man”: “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me … When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves or figments of their imagination, indeed, everything and anything except me.”

This invisibility is not a consequence of conscious bigotry or overtly racist attitudes, Abdul-Jabbar insists. Indeed, quite the opposite: As individuals, he says, “Academy members are decidedly not racists and many have probably worked diligently in their art and perhaps privately to fight racism.” But they are nonetheless enmeshed in a “systemic, institutionalized racism that is so insidious because those practicing it don’t realize it.” Academy voters are most likely to notice black actors, Abdul-Jabbar proposes, “when they play socially familiar roles: athletes, performers, slaves, victims of racism, criminals.” Of the last 10 black male actors nominated for Oscars, he says, eight have played historical figures, all of whom belonged to one or another of those categories.

So what we’re talking about here — what both Glover and Abdul-Jabbar are talking about, in my judgment — is not so much a failure of representation as a failure of perception and vision and imagination. By invoking Ellison, Abdul-Jabbar suggests that Oscar voters literally cannot see certain kinds of non-white performers and certain kinds of films. Another way of phrasing it would be to say that they are imprisoned by a culturally and racially limited notion of what kinds of movies are good movies, what kind of acting is good acting, and perhaps even what people are like and what the world is like.

Maybe the problem is less that Academy members are a bunch of racist geezers than that their tastes are inexplicably boring and often appear entirely disconnected from popularity or cultural relevance or artistic merit. There is a component of unconscious racism in there, which Abdul-Jabbar sums up well, but it’s arguably not the main ingredient. Eddie Redmayne comes with all the signals and markers that identify him as a “great actor,” and he will repeatedly get nominated for playing uplifting roles in “prestige pictures” that bore the pants off every sentient being in the known universe. Idris Elba and Michael B. Jordan don’t arrive with those signals and markers and, God willing, they will never make those kinds of films. They’re too black; that’s surely part of it. You could also say they are simply too interesting.

Shares