On many mornings during the late 1980s, when my husband and I drove down to Hickam Air Force Base, the luminous view from the road above Pearl Harbor made us think of how it must have looked when the torpedo planes came buzzing in on Dec. 7, 1941.

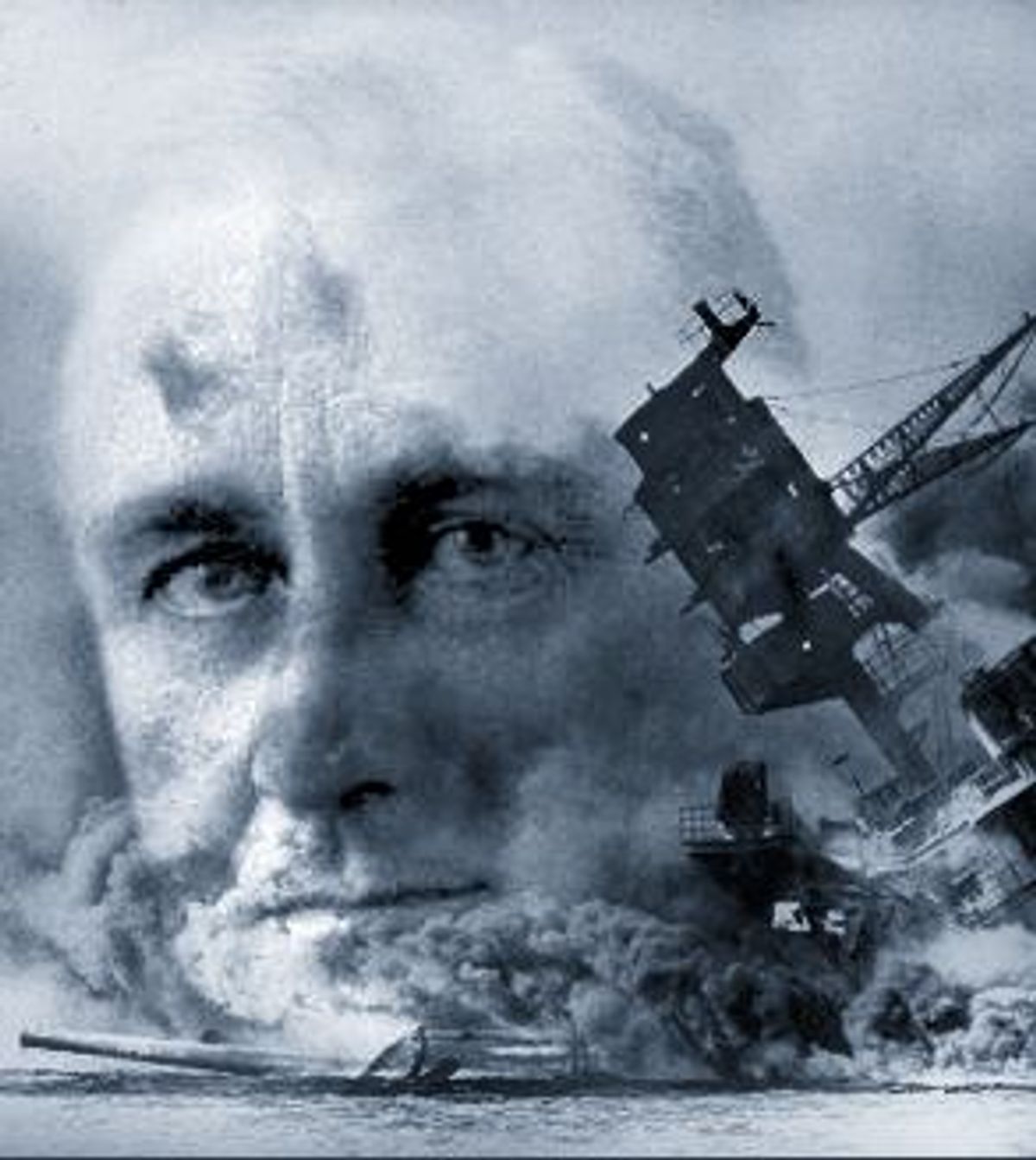

It was "a date which will live in infamy," President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared before Congress the next afternoon, and 60 years later, Americans are talking about that infamous event again. Not because the anniversary has inspired a thoughtful reconsideration of midcentury America's racist assumptions about the Japanese, or a review of the military and diplomatic miscalculations leading up to the debacle, or an attempt to address tricky strategic questions of isolationism vs. engagement. No, we're discussing Pearl Harbor because of the hype surrounding a technically brilliant but soulless movie.

Only in America could such a terrifying, humbling historical event become little more than a deus ex machina plot device, a thunderbolt from the blue that conveniently resolves a hackneyed romantic rivalry. Haven't we seen this before? Explosions, sinking ships, tremulous avowals of love ...? Oh yeah, now I remember -- but this time there's no iceberg.

To avoid giving offense to any group of potential ticket buyers, "Pearl Harbor" gives us a new, anxiety-free, "shit happens" version of the disaster, a no-fault view exemplified by the movie's portrayal of Adm. Husband Kimmel, the senior Navy commander in Hawaii. In the movie, Kimmel -- a dark, stooped, doughy figure in real life -- becomes a clean-cut, prow-faced golden boy who had all the right instincts, but was somehow helpless to escape his destiny. Like all the other pretty heroes and heroines in the movie, Kimmel ended up as a blameless victim of, like, you know, fate.

In contrast, most of the long history of Pearl Harbor revisionism has concerned itself with nailing a scapegoat. The sheer scale of the screwup guaranteed that shrapnel dodging and finger-pointing would ensue, and it became a matter of some political desperation to name one person or group of persons who could take the rap and -- not incidentally -- let the rest of America off the hook.

The most persistent of the various mythologies that grew out of this frantic buck passing was the belief that FDR not only deliberately provoked the Japanese attack but knew when and where it would occur. The story goes that FDR deliberately kept that information from his commanders in Hawaii so the attack would sway American public opinion from its intransigent isolationism. (No one has quite explained how being alert and prepared to beat off the attack would have significantly diminished its political effect.)

The "FDR knew" conspiracy theory was revived again last week in a tendentious article in the New York Press by the left-wing contrarian Alexander Cockburn, who also revives the usual dishonest rhetorical habits of FDR's accusers. Cockburn cites, for example, a 1999 article in Naval History magazine that claims to "prove" FDR's prior knowledge by citing the fact that the Red Cross secretly ordered large quantities of medical supplies to be sent to the West Coast and shipped extra medical personnel to Hawaii before the attack.

These facts, like so many of those cited as proof of FDR's vile plot, can be explained quite readily without resort to the idea of a conspiracy. FDR had pledged to keep America out of foreign wars. At the same time, he was aware that our diplomatic efforts with the Japanese were only likely to buy us time, not permanently prevent war. No responsible leader could neglect the responsibility to be ready for any eventuality, but FDR also wouldn't have wanted the press to become aware of the necessary preparations. That would have been a political disaster and might have derailed his effort to quietly enhance our capabilities before war broke out.

Populist horsefly Gore Vidal, in the course of a book review in the Nation in September 1999, and again in a November 1999 (London) Times Literary Supplement article titled "The Greater the Lie," also lent credence to the "FDR knew" theory by praising -- I can only assume without having read -- the most notorious recent restatement of the theory, Robert B. Stinnett's book "Day of Deceit: The Truth About FDR and Pearl Harbor," first published in 1999 and new in paperback this month. (Vidal also presents the theory in his latest novel, "The Golden Age.")

Stinnett -- whose previous historical work was a suck-up treatment of the elder George Bush's war years -- purported to have new, recently declassified documents to support the idea that FDR was involved in a depraved political plot against our brave boys in uniform. But despite the book's surface appearance of being an earnest and meticulous investigation -- complete with lengthy footnotes and reproductions of dozens of important-looking bits of paper -- it's not hard for a careful reader to see the bilge water pouring out of it.

It's not just that Stinnett's "evidence" -- if it can be dignified as such -- is at best ambiguous and circumstantial. It's not just that his theory, like most classic conspiracy theories, conflicts with reams of other available evidence and tries to make us believe two or more mutually exclusive things before breakfast. It's also not just that he -- for all his apparently knowledgeable blather and the truckload of "documentation" he dumps on us -- apparently doesn't understand some important realities of cryptology and signals intelligence. It's not even that it is impossible to believe that Roosevelt -- who was, without a doubt, wily and subtle -- might have perpetrated such a Machiavellian plot. No, the real reason to think there's no pony in this pile is Stinnett's relentlessly dishonest -- dare I say "deceitful"? -- characterizations of documents, incidents and testimony.

As with other such conspiracy books, "Day of Deceit" received reviews in responsible academic journals like Intelligence and National Security that demolished it, citing its nonexistent documentation, misdirection, ignorance, misstatements, wormy insinuations and outright falsehoods. The consensus among intelligence scholars was "pretty much absolute," CIA senior historian Donald Steury told me in an e-mail. Stinnett "concocted this theory pretty much from whole cloth. Those who have been able to check his alleged sources also are unanimous in their condemnation of his methodology. Basically, the author has made up his sources; when he does not make up the source, he lies about what the source says." In other words, even if Roosevelt were genuinely guilty of these charges, "Day of Deceit" couldn't possibly convict him.

Typical of the kind of porous and dishonest evidence "FDR knew" theorists promote are the "coded naval intercepts" Vidal praised Stinnett for having "spent years studying." Again, Vidal either never actually read Stinnett's book or was -- in spite of his intellect -- somehow dazzled by the book's hurricane of bullshit exhibits. Stinnett's supposedly assiduous study of Japanese intercepts amounts to only a series of rhetorical scams. The most contemptible of these comes during his jumbled discussion of whether the Japanese maintained radio silence during the approach to Hawaii. (It is a crucial argument of conspiracy theorists that the Japanese fleet was detected on its way to Pearl Harbor by radio direction finders around the Pacific, and that FDR supposedly deliberately withheld the location and movements of the Japanese carrier task force from his Hawaii commanders. But if the Japanese did not use their radios en route -- and they have always insisted they didn't -- they couldn't have been found by the radio direction finders.)

After noting several incidents that prove little more than that there could have been a late transmission on Nov. 26, Stinnett goes on to say that he, the intrepid investigator, discovered 129 intercept reports that indicate that the Japanese didn't maintain radio silence during the approach to Hawaii. (None of them are reproduced in the book.) Stinnett then blandly states that these intercepts came from a three-week period from Nov. 15 to Dec. 6. In other words, all of them could have been obtained before the fleet ever left Japanese waters, and before radio silence was imposed. I don't know how Stinnett could believe that his readers wouldn't notice this critical detail, but then, most of the book displays little respect for our intelligence.

Nevertheless, like other conspiracy books before it, Stinnett's was eagerly clasped to heaving right-wing bosoms from sea to shining sea. One enthusiastic reader at Amazon.com, for example, opined that people who could not accept Stinnett's thesis were obviously "brain-washed with liberal red fascist, left-wing extremist, pagan atheistic infanticidal merchant of death beliefs that won't let them face the real ugly truth."

There is probably little hope of reasoning with people like this, but the real problem is that despite dozens of careful debunkings of Stinnett's book and others like it, the "FDR knew" idea still retains its currency with people like Cockburn and Vidal -- who certainly share neither the rabid rage nor the right-wing ideology found in many of their fellow believers. Cockburn (perhaps tellingly) does not even mention Stinnett in his column, yet repeats as gospel many of his most questionable contentions, like the claims of one Robert Ogg -- who is linked by marriage to Adm. Kimmel's family -- to have pinpointed Japanese radio traffic from the Hawaii-bound fleet in the North Pacific.

Cockburn and Vidal are certainly intelligent enough to recognize the holes in a poorly supported thesis if they choose to educate themselves about it. But they seem to want to believe it anyway -- and, worse, to actively promote it. Many other ordinary people I talked to about the theory also seemed to implicitly believe it, most of the time without having read a single book outlining the accusations.

Why? One theory is that conservative hostility to FDR's New Deal continues to the present day, and has over time succeeded in slipping the meme of Roosevelt's political depravity in under the radar of our national consciousness, sabotaging our ability to apply logic to the situation.

Given FDR's notorious "government interference" initiatives like Social Security, banking and securities regulation, farm price supports and -- worst of all -- that pesky minimum-wage and collective-bargaining legislation, it's not surprising that conservative capitalists in the '30s and '40s felt a level of hatred for him that wouldn't be matched until the days of Bill Clinton. (My grandmother, the daughter of a banker ruined in the crash, once told me that the sulfuric name of "Roosevelt" was never uttered at her family's dinner table. Like Clinton in many '90s households, FDR was always referred to only as "that man in the White House.")

To make matters worse, when Roosevelt emerged after Pearl Harbor as the "one who'd been right all along" about our vulnerability to fascist militarism, the isolationist Republican Party -- already staggered by the commie horrors of the New Deal -- was banished to the ninth circle of political hell for the duration (and then some). It accordingly launched an effort to transfer the ultimate responsibility for the debacle at Pearl Harbor from the military commanders in the field, Adm. Kimmel and Lt. Gen. Walter Short, to the Roosevelt administration.

But given that one of the most fundamental duties of military command is ensuring readiness to meet attack, the only way to completely exonerate Kimmel and Short was to make a case that they'd been deliberately set up. Thus was born the first wave of Pearl Harbor conspiracy theory, which was America's favorite paranoid fantasy until the Kennedy assassination. It became such a cherished conservative myth that Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., instigated yet another official investigation of Pearl Harbor (the 10th) in 1995.

Despite that 1995 investigation coming to much the same conclusion as all others before it, the contrarian "FDR knew" meme lived on, and reached its apogee of respectability when the new Republican-dominated Congress recently passed a resolution absolving Kimmel and Short of any responsibility for the tragedy and restoring them posthumously to their highest ranks. It was a move that many people believe was extremely unwise. Military tradition, which runs much deeper than military law, has always held that whatever happens on your watch is your responsibility and that it is your duty to accept the consequences, however unfair they may seem. Congress' official endorsement of buck passing has not gone over well with everyone.

Truth be told, there was plenty of blame to go around, both in the field and in Washington. The constant tension between ensuring secrecy and giving operational units access to essential intelligence may not have been resolved in the best possible way before Pearl Harbor, and in any case, intelligence functions were tragically fragmented and dispersed. Robin Winks, professor of history at Yale University and author of "The Historian as Detective: Essays on Evidence," agrees with the conclusions of other investigators that there was a "massive operational failure" to use the intelligence we did obtain to good effect. "I believe we had the information, that it was not understood by those who had it, that those who most needed to have it didn't see it, and that FDR did not know, though perhaps by only the margin of a very few hours."

Yet the rumor persists, and is usually based on the idea that we had access to the Japanese navy's operational codes and not just the "Purple" diplomatic code that was the basis for the famous "MAGIC" intelligence reports. Vidal, for example, makes a typical flat-footed declaration about it (based on the Stinnett book) in his discussion in the Nation: "Although FDR knew that his ultimatum of November 26, 1941, would oblige the Japanese to attack us somewhere, it now seems clear that, thanks to our breaking of many of the 29 Japanese naval codes the previous year, we had at least several days' warning that Pearl Harbor would be hit." The idea that we were reading more than consular communications is also obliquely alluded to but not developed in the movie "Pearl Harbor."

But researcher Stephen Budiansky, in an article for the Proceedings of the Naval Institute, details evidence rebutting that contention, which he found while researching his book "Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II."

In March 1999, Budiansky found documents that had been declassified some years ago but not yet processed by the National Archives staff, and thus not listed in the finding aids for researchers. The papers turned out to be contemporaneous, month-by-month reports on the progress of the Navy code breakers, each date-stamped, covering the entire period from 1940 to 1941. They showed, Budiansky said, that the first JN-25 code (designated "Able," or JN-25-A) was laboriously cracked with help from the new IBM card-sorting machines (and some lazy Japanese encoders) in the fall of 1940.

But then, heartbreakingly, the Japanese switched to a new version of the code ("Baker" or JN-25-B -- in a typical display of ignorance, Stinnett claimed in his book that there was no such thing as a JN-25-B code) in December 1940, a year before the attack on Pearl Harbor. At that point the code breakers completely lost their ability to read the operational communications. Going back to the drawing board, and with the aid of a supersecret collaboration with British cryptologists in Singapore, the Allies managed to recover a small fraction of the code groups and additives (which changed again that summer) by Dec. 1, 1941 -- but most of what they could read by then was numerals, not words.

Yet, in classic conspiracy theory fashion, the rumor that we had access to Japanese naval communications has been sustained down the years by portentous reference to documents like a March 1941 message from Adm. Thomas Hart, commander in chief of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, which Stinnett reproduces in "Day of Deceit."

Stinnett claims the message indicates "solutions" to the JN-25 code were being shared with the British. Clearly, however, what is being shared is only preliminary data and some bits and pieces recovered from an accumulation of old communications in earlier additive groups. The admiral, encouraged by the prospect of British help, directs his code breakers at Cavite (Corregidor) to work exclusively on JN-25. The only thing this document proves, then -- other than Stinnett's dimwittedness -- is that this crucial Japanese operational code was not solved once and for all in 1940.

Another of the common tricks used to sustain the "FDR knew" theory is the publication of supposed "smoking gun" diplomatic messages in the "Purple" code (a more "routine" consular code) that naval intelligence often waited days to read. These messages were regarded as relatively unimportant and weren't decoded or translated until after the Pearl Harbor attack -- sometimes not for years afterward. It's a phenomenon Budiansky is familiar with. "It became a joke at the Archives," he wrote in a message to a military history mailing list, "to see how many people would rush to show John Taylor, the national security archivist, their 'discovery' that the U.S. was reading JN-25 before Pearl Harbor ... John would point to the date of decryption at the bottom of the sheets and watch the researcher's face fall."

One of the things that is most notable about the way the "FDR knew" theory is sustained is that its methodology parallels that of so-called creation science. The trick in both instances is to assiduously ignore all the mountains of evidence in favor of the theory you are trying to disprove and to focus instead on tiny apparent discrepancies and supposed "missing links" in the record. "True to the M.O. of all conspiracy theorists," Budiansky notes, "the ABSENCE of further documentary evidence actually confirms [the] thesis by proving that a 'cover-up' has taken place."

The conspiracy buffs always point to the fact that there are apparent gaps in numbered message series, that the National Archives has not gotten around to declassifying all the millions of pieces of paper from the war, that certain material provided to congressional investigations in the early days of the Cold War was perhaps too compulsively censored and that some supposedly crucial material is missing, such as the log of the passenger liner SS Lurline's radioman Leslie Grogan, who claims that he heard Japanese radio traffic in the North Pacific just before the Pearl Harbor attack. ("They were just blasting away.")

But the SS Lurline was on a southerly route to Honolulu from Long Beach, Calif., so the radio signals Grogan heard coming from the northwest could have been from Japan's shore-based radio facilities, not the carrier task force. Grogan claims he took his original log to naval authorities in Hawaii after the Lurline arrived on Dec. 3, but they didn't seem particularly interested. The Lurline's radio log was checked out of the National Archives without a date or signature sometime in the '70s, about the time another Pearl Harbor conspiracy theorist, John Toland ("Infamy"), was doing his original research.

But this "mysteriously" missing material could just as easily provide definitive proof that the "FDR knew" gang is full of it. Given that conspiracy theory has become, in the words of Paul Miles, Tomlinson Fellow in the History of War and Society at Princeton, a "cottage industry," it struck me that some of the documents in question could have been spirited away by people with another agenda entirely. Look at me! I can concoct conspiracies too!

"Anyone who does intelligence history (as I do)," says Robin Winks, "knows it is very difficult, highly technical and open to conspiracy theory, because inevitably some material is missing, and at times some material deliberately lied with a view to disinformation." For example, and apropos of the SS Lurline material, the Japanese later stated that they attempted to produce bogus radio traffic right before Pearl Harbor in the hope that it would confuse intercept agencies about the location of the silent fleet. It might not have fooled military professionals, but Leslie Grogan was an amateur.

The conspiracy theorists, in parallel with the creationists who maintain that God must have placed fossils in the ground to test his people's religious faith, also think that Roosevelt and his political allies managed not only to cover up their dastardly deeds but to fabricate thousands of linear feet of documents in order to camouflage the truth. It is perhaps remotely possible that some kind of massive effort of that kind was instituted here in America in the midst of wartime, but unless we want to believe that our former enemies have destroyed or manufactured material to burnish Roosevelt's reputation, evidence from Japanese archives also backs up the idea that the attack was a surprise to FDR.

Linda Goetz Holmes, for instance, a Pacific war historian with the Interagency Working Group at the National Archives and author of the book "Unjust Enrichment: How Japan's Companies Built Postwar Fortunes Using American POWs," told me about the findings of a Japanese historian whose research in his country's recently declassified files only became available in the U.S. in 1998. He revealed considerable documentary evidence of Japanese satisfaction with how well "our magnificent deception" was working in Washington.

Yet the "FDR knew" meme continues to thrive with supporters like Cockburn and Vidal, whose credibility should suffer from such carelessness, but somehow never does. The case of Vidal is particularly shocking, because he prides himself on demolishing cultural mythology, debunking "court historians" and pursuing the truth. Yet he embraces a dishonest "researcher" like Stennitt and lends his literary aura to a tissue of lies.

In 1941, both military and civilian authorities were operating from extremely bad -- and, it's important to note, very racist -- assumptions when it came to the Japanese. We simply couldn't believe that the "little beasts" had gotten the drop on us, or as Stanford historian David M. Kennedy indicates in his book "Freedom From Fear," that we as a people had made "systematic, pervasive and cumulative" mistakes that led to the disaster.

That there are rational, wide-reaching and comprehensible reasons for our failure to be prepared at Pearl Harbor is not an idea that sits well with most Americans. We'd much prefer to believe that the calamity wouldn't have happened if we weren't deliberately set up. In that sense the "FDR knew" theory is very comforting. It essentially absolves everyone except the nefarious Roosevelt and his diabolical cronies; it implies that everyone else, and all their procedures, decisions, organizations and attitudes, were impeccable. If only a better man had been in charge, this fairy tale goes, the yellow horde wouldn't have succeeded.

Such a view handicaps our ability to learn desperately needed lessons from the debacle. I'd much rather we admitted our mistakes -- all of them -- so that when future military men and women look out over Pearl Harbor in the morning they will be reminded, as I always was, of how quickly our smug assumptions can be blown out of the water.

Shares